‘People have no idea’: How smart devices spy on us and reveal information about our homes

Pioneering research has discovered how smart devices talk to Android apps and each other to share data that allows them to know who enters a home, when, and how much they earn

The home has traditionally been the family’s most private place. But first the mobile phone and now smart devices have entered that space. Their digital conversations mean that, often without the users’ knowledge, they share intimate details about the home that were previously impossible to obtain. Until now, research on these devices focused on external risks: is it possible to access a home camera from the internet? Is a smart speaker vulnerable to eavesdropping? Today, pioneering work by several universities and research centers has discovered that beneath the superficial calm of a house, there lurk many risks.

“One of the biggest problems is the invasion of privacy,” says David Choffnes, professor at Northeastern University in Boston and one of the co-authors of the work. “These weaknesses give attackers a clear idea of what is in your home, who is there, as well as where they are moving and when. We discovered that some apps take advantage of this to collect data from homes, for purposes that have nothing to do with their function. If our homes are our most private place, it seems like a serious invasion of privacy to me,” he adds.

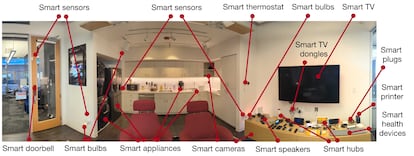

Choffnes and his team at Northeastern set up a “living lab/apartment with over 100 devices,” dubbed Mon(IoT)r Lab, at their university. It’s like a big party, but with devices. In the lab, researchers from the university and other centers study the entire variety of behaviors and relationships that occur between the devices, from light bulbs and refrigerators to routers and speakers, which communicate with each other. This research also studies all of their connections with apps, both those that manage these devices and others that Android users have on their mobile phones, and both those who live in that house and those who visit it. Apple’s environment is much more private.

EL PAÍS has asked Google, which bought Android in 2005 and has a line of smart devices, about this study. A spokesperson responded: “We greatly appreciate the security community’s research. We are constantly improving our security protections to help keep Android users safe.” The Android environment, due to its nature and number of actors, has a lot of challenges to overcome.

“I don’t think people have the slightest idea that all devices connected to Wi-Fi talk to each other in some way. And that has implications,” says Juan Tapiador, professor at the Carlos III University and another co-author of the study.

What type of information do these devices share? They are not like the conversations or messages we send. The type of information that they share ranges from unique device addresses (MAC), serial numbers, versions of vulnerable protocols, or even names of specific devices such as “Joe’s speaker in the dining room.”

All this information, and the services to which they connect, allow many details of our lives to be inferred, and could provide a digital fingerprint of our home, which would allow targeted attacks or surveillance. “The uncontrolled exposure of this information,” says Narseo Vallina-Rodríguez, researcher at Imdea Networks and co-author, “allows advertising services or spy applications to create a digital fingerprint of your home that uniquely identifies it or can infer your income level and habits.” Not only that, if these devices scan for new information frequently “they can infer who enters and leaves the house and your social structures to monitor their activities through networks and devices,” adds the expert.

We do not fully understand the risks

Users might think that all this is not such a serious issue because the information does not seem so private. They tend to misunderstand the risks involved in gathering dozens of specific pieces of information about a home. For example, this data is captured by apps that we carry on our phones and they collect the serial number of the router or the name of the connection, which allows us to know the location (without even accessing the device’s GPS). There are pages where Wi-Fis from all over the world are mapped. If two mobile phones access the same Wi-Fi, you not only know that they are close, but also where they are. If an app on the visitor’s mobile scans how many smart devices are there, and which ones, that data can help calculate the household income of that home.

“One of the things that was most difficult for us to understand is that the informative value of technical data is sometimes difficult to predict,” says Tapiador. The SSID, which is the name of the Wi-Fi network, is a good example. When a mobile scans the available networks, the name of all those nearby can be seen. “There are many online services that provide you with geolocation information based on that name,” continues Tapiador.

A specific example of the fearsome use of the combination of information that can be gathered thanks to these devices is given by Vijay Prakash, a researcher at New York University, and co-author of the study: “If a malicious actor abuses the information that floats freely in smart home networks they can track a user across devices from multiple vendors. For example, if a malicious application takes fingerprints from several users’ smart homes, and some of them visit the home of one of the other users — let’s call her Jane — with their phone on them, the application could infer Jane’s social relationships and schedules in which other users visit her.” It must be taken into account that this would not happen just once, but continuously.

The apps analyzed in the study had millions of downloads that contained software that collects this type of information. If an app has access to location data and scans Wi-Fi networks, it already knows that those networks are in that place: “This is crowdsourcing carried out by millions of people,” Tapiador continues. “There are maps with those names from all over the world. When you tell someone, ‘hey, this light bulb is picking up the SSID or MAC address of the router’ it’s the same as saying, ‘this light bulb is picking up the location of your house.’” That is not the only problem: “The question is what other relationships they can build from there. Allowing you to have access to traffic generated by your devices can have unanticipated consequences,” he says.

Without legal permissions

Many of these examples are not legal, but the Android environment is a jungle: “These practices have many implications, since they often occur without any type of user consent, and sensitive information such as geolocation or devices and users (data protected by the General Data Protection Regulation) is also obtained,” says Vallina-Rodríguez.

This is an example of the complex dance of conversations that devices have within a home, as explained in the research: “Six [of home device] applications transmit the [unique MAC] addresses of devices to the cloud, and the recipients are their own domains [for example, Alexa] or third-party providers such as Tuya, (a [home device] platform provider, based in China), and Amplitude, which is an analytics service.”

To a human, this combination of data may seem overwhelming and unbearable. But for machines it is their daily work. Beyond hypothetical security risks, this information feeds the enormous, dark machinery of global marketing and advertising, also called “commercial surveillance.” At the moment it is not happening, but just as we receive personalized advertising on mobile phones, the industry could identify our home and tailor the advertising to our economic and family situations: what is easier than discovering when a couple has separated or how much the friend who has come to your birthday party earns?

“Just as many pages create a fingerprint of the user so they can recognize them between sessions even if they delete their cookies,” says Tapiador, “we saw that it is possible to do the same for a home using the devices. It is a theoretical observation in the sense that personalization aimed at specific homes is not permitted today, but the possibility that it can be done still exists,” he adds.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.