Ceramics reveal the boundaries of Western Europe’s first state

El Argar had a centralized system for the production and distribution of its pottery vessels and clay objects, all made from material sourced from a single location

While in the East, Egypt was entering its Middle Kingdom, Hammurabi was building the Babylonian Empire, and the Minoan culture of the First Palaces was flourishing in Crete, Western Europe was still emerging from the Neolithic era — except in the southeast of the Iberian Peninsula.

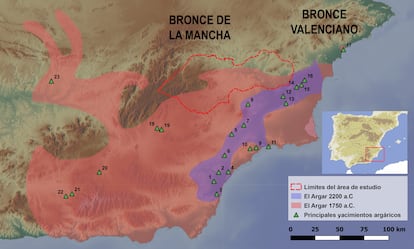

Between northern Almería and southern Murcia in Spain, the Argaric culture emerged over 4,000 years ago. In just a few decades, it reached its peak, covering an area roughly the size of Maine. Dominating copper mining and supported by extensive grain production on the plains, the Argaric people had already developed social classes and a form of aristocratic parliament. While dozens of cities and hundreds of settlements are known, the full extent of their power was previously unclear. However, a recent study of their pottery has shed light on the boundaries of this ancient civilization.

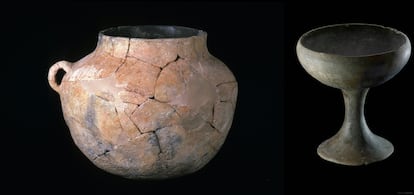

“In the Bronze Age, pottery was like plastic today; it was the most common commodity of the time,” says Adrià Moreno Gil, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology in Germany. “They used it for eating, cooking, storing, transporting... even for burying their dead.”

This practice, in particular, makes the Argaric people stand out — they buried their loved ones within their homes, sometimes inside large jars. As with nearly every ancient culture, Argaric pottery has unique shapes, designs, and styles. Classical archaeology has long used these formal differences between pottery types to define distinct cultures. However, style alone does not reveal the full history of a culture.

To uncover more, Gil Moreno and colleagues from the Autonomous University of Barcelona mapped 1,643 ceramic remains from 61 settlements, some of which were Argaric, while others belonged to neighboring groups. The results of their work have recently been published in the Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory.

As Moreno Gil explains, in Europe, “small-scale local production was common to meet local needs.” Even for forms that were widespread across the continent, such as the Bell Beaker, “it wasn’t that these forms spread across Europe from a single location; rather, it was a production style adopted by various regions, but it was still produced locally,” he adds.

However, in El Argar, things were different. “First, because it’s standardized; in the rest of the peninsula, we see a wide variability of forms. Since everyone made what they could or wanted, there were many different styles. In contrast, in El Argar, we have eight forms, and all eight are found everywhere,” the archaeologist explains. Furthermore, a repetitive pattern of capacities appears across the region. “That tells us that ceramic production is much more regulated by a central or centralizing entity,” he says.

But they discovered something else. As Carla Garrido, a researcher at the University of Barcelona and co-author of the study, explains: “Traditionally, archaeology has always studied pottery from a stylistic perspective: the shape of the piece, the type of decoration, whether it’s painted... But those of us who dedicate ourselves to studying ceramics as a human-made element perform what’s called an operational chain study, analyzing the entire process from obtaining the clay to assembling the piece and finally firing it.”

When studying the clay composition of hundreds of pieces recovered from the 61 settlements, the researchers discovered that they all came from a single site, perhaps two, located in the south of what is now Murcia province. The Argaric ceramics were made from clays sourced from the Sierra de la Almenara, situated in the southern part of modern-day Murcia, at the northernmost tip of the Penibética mountain range. This site is a considerable distance from the Argaric settlements farther to the west.

“We’re not talking about gold, silver, or metals; we’re talking about ceramics, and in very large quantities,” says Garrido.

The fact that an everyday object, requiring human labor, was being produced in one place and distributed across a vast territory — sometimes over distances of up to 100 miles — “tells us that the capacity for territorial control and material distribution structures must have been highly developed,” adds Moreno Gil.

This centrality and hierarchical structure of production and distribution serve as the key to defining the boundaries of El Argar. “Once we identified and defined the type of paste they used, we began to observe differences at the border sites, where ceramics made by other groups appeared, simply because of the clay type. We are fortunate that in El Argar, everything is so homogeneous,” explains Garrido.

In this way, the researchers were not only able to delimit the boundaries, but also to track the Argaric expansion itself: “Having the Argaric paste so clearly defined allowed us to demonstrate how the border shifted. In other words, we could see where Argaric ceramics began to appear, with a significant presence in some sites to the north,” Garrido says.

The eastern border of El Argar was defined by the Mediterranean Sea, which also marked its southern boundary. To the north, the civilization didn’t extend beyond the Crevillente mountain range (in Spain’s Alicante province), but it was to the west where its territory expanded, and where pottery has been instrumental in helping to define its limits.

This research was carried out in only a portion of the area, focusing on the headwaters and middle section of the Segura River valley. “Adrià traveled 150 kilometers from site to site,” says Roberto Risch, professor of prehistory at the Autonomous University of Barcelona and the senior author of the research. “But we hypothesize that El Argar had about a thousand kilometers of border,” he adds. They hope the pottery will help confirm this.

“Being Argaric isn’t just about burying your people in your homes. Being Argaric isn’t just about having certain taxes. It’s about those eight ceramic forms, and not just their shape, but how they’re made,” Risch explains. “All the pottery from that culture is made with the same raw material sourced from very specific mountain ranges, which are also the [foundational] territory of El Argar,” he adds.

The study of ceramics further supports the interpretation of El Argar society as an integrated and cohesive political and economic organization, with far more developed systems for production and distribution of raw materials and goods than previously thought. For Risch, “these results significantly support the hypothesis that El Argar developed the first state structures around 1800 BC in Western Europe.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.