Humor as a tool to understand the US immigration system: ‘There is no easy way to move to America’

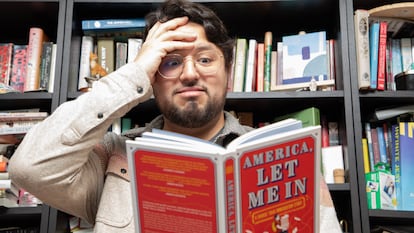

Comedian Felipe Torres Medina’s new book, ‘America, Let Me In: A Choose Your Immigration Story,’ uses funny anecdotes to illustrate the challenges migrants face in obtaining visas

Felipe Torres Medina, 33, moved to Boston, Massachusetts in 2013, with a clear goal: to write comedy for television. But the path was far from straight-forward.

His first step was to pursue a master’s degree in screenwriting, while simultaneously traveling to New York on weekends to train in improvisational theater. Little by little, he began contributing to well-known publications like The New Yorker and BuzzFeed, while making a living in the advertising industry. Six years later, he landed a position on the team at The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, where he currently works writing jokes. Unknowingly, as he was building his dream career, he was also learning about the complexities of the immigration system. To work in the field he admired so much, he needed to secure the right visa.

“My first panic attack was due to an immigration situation,” he recalls. Obtaining a visa involves deciphering processes explained in technical language, investing money, and grappling with the uncertainty of the outcome. “Every American has an opinion on immigration,” Torres Medina reflects from his apartment in Harlem, New York, “but very few understand the system and can explain it.” Faced with this, he decided to create a humorous guide.

In America, Let Me In: A Choose Your Immigration Story, Torres Medina uses a “choose your own adventure” format to immerse readers in immigration scenarios that blend bureaucracy and humor. For instance, on page nine, readers must select the difficulty level. If they choose “Easy,” they are directed to page 11, where it says: “Wrong! There is no easy way to move to America.”

The book includes stories like that of a French millionaire who decides to start a pastry business, and a student who, after taking the hand of a strange woman, finds herself in a meadow filled with centaurs who are “incredibly attractive, but in a tender and affectionate way.” It also shares anecdotes from Torres Medina’s own journey toward his dream of writing for television. As the narrative unfolds, readers encounter satirical explanations of the various types of visas available, along with the advantages and difficulties of obtaining them.

On the occasion of the launch of his book, the author speaks with EL PAÍS about his career and hopes for his debut novel: selling 10 million copies and winning a Nobel Peace Prize. Easy.

Question. Comedic stories about immigration aren’t common. It’s a topic fraught with difficult procedures and experiences, yet you chose to approach it with humor. Why?

Answer: I realized that Americans have no idea about this immigration system. I remember at the end of my master’s degree, they were like, “You have to get a job.” And I was like, “Yeah, but I also have to get an OPT permit.” They weren’t aware of all the limitations I had as an international student. Then, in 2016, I was getting my artist visa. Technically, it’s called a visa for Aliens of Extraordinary Ability, which sounds absurd! It was Donald Trump’s first election. And finding yourself in that dichotomy where the candidate who’s going to win is saying that countries “aren’t sending their best people” to the United States, while the government is asking me for 10 letters of recommendation from experts in the field to prove that I’m a person of “extraordinary ability,” presents a very absurd juxtaposition. That’s where the humor comes from. Since I’m not an immigration lawyer, an activist, or a journalist — I’m a comedian — what I could do was write something funny. And Latin Americans are people who deal with absurdity all the time, and we deal with it with a lot of humor.

Q. Where else did you find humor and absurdity in the U.S. immigration system?

A. It first happened while filling out a tourist visa application, which has questions like: “What is your mother’s name? What is your father’s name? How many times have you come to the United States?” And later: “Have you participated in human trafficking? Have you been part of a terrorist organization?” Obviously, you can’t lie on those forms, so it seems absurd to me to think about the person who’s going to answer “Yes.” But in the process of writing the book, I also discovered that the H-1 visa, which is the work visa, is based on a lottery. So students from all over the world come here to receive training with, supposedly, the best education in the world in science, computers, whatever. And, at the same time, the largest companies — Facebook, Google, etc. — can’t hire them because suddenly that person comes from India, China, or Colombia and needs an H-1 visa. So, even if you have the best grades in college, the best recommendations, and the best job offer, you’re still subject to a lottery.

Q. When did you start thinking that these observations could be turned into a book?

A. It was in 2017. That year I sat down to write, but I didn’t like what I wrote. I wasn’t ready. One thing I noticed was that I didn’t want to just talk about my story, because memoirs are written by very interesting people who have had very interesting things happen to them. I’m not that interesting. Many years later, my friend Reed Kavner, who’s a comedian and producer in New York, invited me to a comedy show called Next Slide Please, where you make a PowerPoint presentation on any topic you want. I did an interactive show where the audience could choose any of these immigration paths that would later appear in the book. They were stories based on visas I knew, that my family and friends had received. And people liked it. When I sat down to write the book, I decided to include the O1 visa for extraordinary talent and the F1 student visa. Which led me to think, “I have personal experience and some funny things have happened to me that I can include.”

Q. And for whom is it written?

A. For everyone. At least to some extent. My wife is American, and she’s also a comedian; she writes for John Oliver’s HBO show. She asked me: “Wouldn’t you have liked to have a book like this when you were a student doing this? Wouldn’t you have liked to have someone who could talk about visas in a friendly way?” So, in part, the book is for all the immigrants who are trying to do this. But it’s also for Americans, for my friends who ask a thousand times: “But are you a citizen yet?” And it’s also for the anti-immigration conservative who has very clear opinions and demands that people “have to come here the right way.” Here I’m showing them how complicated that path is.

Q. When you open your book, you find a narrator speaking directly to the reader. What inspired you while writing the book?

A. Yes, the book has that conversational tone, a bit inspired by Hopscotch [by Julio Cortázar]. Another inspiration was Italo Calvino’s book, If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler, which is also super playful because it starts out by saying, “You are about to begin reading Italo Calvino’s new novel. Relax. Concentrate. Dispel every other thought.”

Q. In the acknowledgments, you mention George Saunders…

A. He also inspired me. His stories are funny, but he manages to talk about heavy stuff and still have a brilliant humanity and humor.

Q. And as a comedian, what has inspired you?

A. On television, Monty Python is a group of English short comedy sketches from the 1960s and 1970s. What they did was present humor that was both very silly and very intelligent, and that’s what I find fascinating. Also Les Luthiers, from Argentina, who I think were inspired by them. Stephen Colbert, who is now my boss. And Tina Fey. It wouldn’t have occurred to me that you could write funny books if I hadn’t read Bossy Pants, which is her memoir. As a huge nerd and Star Wars fan, I later discovered that Carrie Fisher, who plays Princess Leia, was a great comedian. Her writing has been quite formative.

Q. The book doesn’t mention undocumented immigrants. Why not?

A. This book doesn’t tell those stories because, for me, they require a more serious tone. All I’m saying is that the people who come here illegally, for the most part, are trying to find a better future. They came in the same way and under the same conditions as the 20th-century waves of migration from countries like Ireland, Poland, Germany, and Russia. I think it would be worth learning all those stories, but not in this book. I don’t find them funny. Someone else might make fun of them, but not me.

Q. And they are making fun of them…

A. Yes, and they work for the federal government.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.