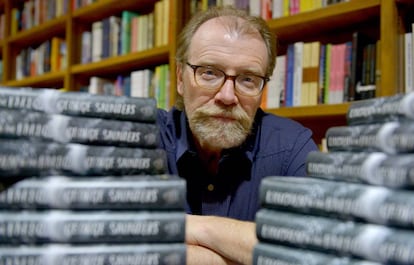

Short-story master George Saunders: ‘Social media instantly turns you into a ferocious version of yourself’

The American author is back with a new anthology that highlights the struggle against algorithmic ‘mind control’

In the stillness of the night, a voice intrudes upon her thoughts. It tells her how she must behave to win over Randy. Who is Randy, she wonders. She doesn’t know, so she gets out of bed, dons her nightgown, descends to the kitchen, and powers up her computer. This is how author George Saunders, winner of the Booker and PEN/Malamud awards who grew up in Chicago, weaves his tales. He creates characters for the thrilling world he wants to inhabit. His stories are like untamed creatures, leading readers on a journey of self-discovery. “I love the idea of them being like little wild animals, you know? Isn’t that what they should be?” he asks.

The man who some consider the greatest living American short-story writer is somewhere in Los Angeles, smiling in front of a computer. It’s morning for him when he answers my video call, and it looks like he’s wearing a comfy sheepskin jacket. Saunders says he’s still getting used to L.A., which seems futuristic to him. “So, for the first time, we’re city folks, and I must say it’s actually pretty good.” He moved there to be close to his daughter, although he still teaches at Syracuse University in New York. It’s Valentine’s Day, and Saunders believes Gloria and Randy, the protagonists of that late-night story that started with a late-night voice, are still together. The short story is titled Sparrow and is part of Saunders’ Liberation Day: Stories (2022) collection.

“I don’t believe soulmates exist, but souls that fit together definitely do. Every love story is some version of that type of fit. One has to be willing to adapt, to blur oneself a little, to fit into another person’s life. And the other person should do the same,” he said. Saunders talks about how he feared that he would have to throw away that “little animal” that began as a voice in Gloria’s head. “I didn’t feel like telling another love story like that.” But the story evolved into a reflection on “how cruel the world can be to someone in love.” How did that happen? “I wrote the story in one night at the kitchen table, but I worked on it for months.” That’s how it works for Saunders, who writes four or five hours every morning. Most of this time is spent rewriting stories and exploring ideas for new ones.

Saunders has only written one novel — the brilliantly disruptive, funny and award-winning Lincoln in the Bardo (2017). He sees fiction as a “garbage detector,” pinpointing societal wrongs while serving as a catalyst for change. “I consider myself a post-postmodern writer. I’m not looking to destroy everything unless it’s a good kind of destruction, in a happy sort of way. I strongly believe in positive destruction. Fiction can disrupt how we come to troubling conclusions, and offer respite and space to think outside of every plane,” he said. Even though he claims not to think about specific topics while writing, Liberation Day can be seen as a modern-day manifesto on the battle for “mind control” that rages in our world.

“In at least three of the short stories in the collection — Liberation Day, Ghoul and Elliott Spencer — it’s clear that the writer [Saunders sometimes talks about himself in the third person] is thinking about social media. If it were 1485, your ideas would be local, from your family and town. Nowadays, ideas come from afar. Add not just ideas, but an agenda imposed on you, altering your thought process. These stories touch on mental autonomy and its challenges. How can I stay true to myself with all this input infiltrating my mind? A century from now, people may call this the era of altered minds,” said Saunders.

Controlled and altered minds. By what — algorithms? “Altered by the captivating technology we live with, and yes — the algorithms. The abundance of information we allow in contributes to all the violence and unhappiness today. How can we find happiness with so much suffering around us? While suffering and cruelty have always existed, we used to be shielded by our surroundings. Now, there’s no protection,” he said. “Social media doesn’t want you to think for yourself or spend time alone with your thoughts. I don’t know for what purpose. It instantly turns you into some kind of animal, some kind of monster, a ferocious version of yourself that automatically has an opinion on things you know nothing about.”

The writer, who attended a school run by Catholic nuns, is now a Buddhist and practices meditation. He tries to protect his mind against invasions of all kinds, and he’s been doing it since the beginning. “When I got my first smartphone, I remember I was reading some Russian authors [he loves Gogol, Isaac Babel and Chekhov]. Suddenly nothing seemed to make sense. My reading comprehension plummeted. I had to tear myself away from the screen for a while to understand the stories, to get the color back. That moment was both fortuitous and terrifying at the same time.”

Saunders is currently reading January, a novel by Argentine writer Sara Gallardo. “I’m fascinated by how she uses stylistic elements to add tension to the story.” He also says he’s working on a new novel, his second in a 40-year literary career. “But I’m still at the beginning,” he said. “We’ll see.” Saunders is convinced that the only thing to do these days — besides protecting your mind — is to try and grow in some way. “It might seem tough, but I truly think that everything going on with us can be turned around. My students are already doing it. They’re trying to ensure that the flame doesn’t go out, trying to be a little kinder every day. That’s my only goal right now. Be more loving, more present and more honest every day. Accept the complexity of the world without despairing — despair is our worst enemy. Perhaps that’s why all the cynical forces out there love it. Let’s keep our distance from them.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.