Seven unpublished short stories by Julio Cortázar discovered in Uruguay

They are part of an early version of ‘Cronopios and Famas’ by the Argentine author, a decade before the book was published

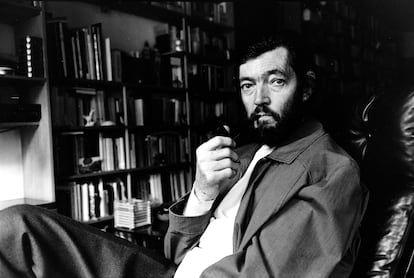

At the age of 37, Julio Cortázar led a solitary life as a provincial teacher, with three books published in Buenos Aires that garnered little success. However, everything changed when he permanently moved to Paris in November 1951. It was during this time, in the aftermath of Juan Domingo Perón’s rise to power in Argentina, that Cortázar’s published Bestiario (1951), the first book he wrote using his real name. Like the others, it struggled to find an audience, but Cortázar remained resolute. Over a decade would pass before the publication of his iconic work, Rayuela (Hopscotch, translated by Gregory Rabassa) and the emergence of the Latin American literary boom. Around this time, Cortázar wrote to a friend in Argentina and shared the new literary concept he was imagining — fictional creatures he called “cronopios.”

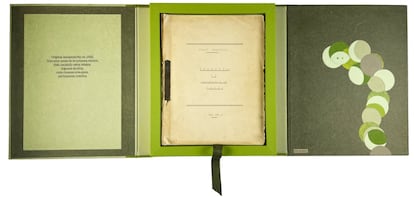

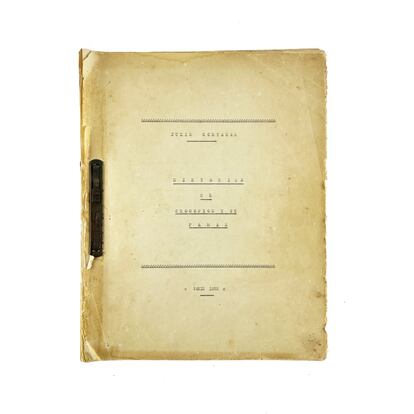

Ten years later, Cortázar published Historias de Cronopios y de Famas, simply translated into English as Cronopoios and Famas. It’s a collection of short musings about daily life, with playful instruction manuals for crying, attending a wake and climbing a staircase. It also includes some very brief chapters featuring the cronopios — the idealistic, sensitive and unruly creatures who became some of his most beloved characters. The cronopios stand in contrast or opposition to famas, who are rigid, organized, and judgmental, if well-intentioned. Now they have seven new siblings. The son of a Uruguayan collector who died in 2019 found a typewritten version of the book in his father’s house. It consists of 46 short stories that Cortázar sent to a friend in Buenos Aires. Of these, 35 were published in the official 1962 edition with minor changes, and another four appeared in magazines around the same time. Seven were never published and languished in a dusty box for decades. After a year of expert analysis, the manuscript will be auctioned on October 12 in Montevideo by the Zorrilla and Hilario auction houses, from Montevideo and Buenos Aires, respectively. A reserve (base) price of $12,000 has been set.

The current owner prefers to remain anonymous, and his father was an unknown collector, according to the auction houses. If the next owner intends to publish them, there will likely be a lengthy negotiation process with Aurora Bernárdez’s heirs, who inherited the Cortázar estate. Only the titles of the unpublished stories have been revealed: “Inventario,” “Carta de un fama a otro fama,” “Mariposas automáticas,” “Los viajes y los sueños,” “Diminuto unicornio,” “Rabia del espejo” and “Rey del mar” (in English, ”Inventory,” “Letter from one fame to another,” “Automatic butterflies,” “Travels and dreams,” “Tiny unicorn,” “Mirror rage,” and “King of the sea.”)

“The published edition includes stories written in poetic prose, with a philosophical backdrop, resembling sociological sketches, always infused with humor and a touch of tenderness. The newly discovered stories follow the same style,” said Lucio Aquilanti, an antiquarian bookseller and academic who is well-versed in Cortázar’s work. Aquilanti is one of the few people who has read the unpublished stories. Nearly a year ago, the family of the deceased collector contacted him to find out whether the folder with old papers that they were about to throw away had been written by one of the most prominent Latin American authors of his time. Aquilanti compared the manuscript with others from his personal collection, which is held in Argentina’s National Library. The handwritten corrections and typography match Cortázar’s style, as well as the typewriter he used at the time. At least four letters sent to friends in Buenos Aires between June and December 1952 support the authenticity of the manuscript.

“You already know about my cronopios. I’m sending you a copy of my book, Historias de Cronopios y de Famas,” Cortázar wrote to his friend Eduardo Jonquiéres (an Argentine poet and painter) on September 20, 1952. Three months later, he wrote another letter to Jonquiéres, complaining about the indifferent silence of everyone who had received his manuscript. “Didn’t Baudi [editor and writer Luis María Baudizzone] pass on to you my little cronopios and famas? I want you to read them because they are very charming, sad, and touching. I am very happy with them, but I am afraid that Baudi found them awful, judging by his ominous silence.” Aquilanti replicated these letters in an article discussing his research on the unpublished manuscript, which concludes, “I can confirm without a doubt that it is an original typewritten work by the author and is of great significance.”

The year-long investigation confirmed that the manuscript was typed on the Royal typewriter Cortázar used until 1966, when Aurora Bernárdez bought him an Olivetti Letera 32. However, the mystery of how it came into the hands of a private collector from Uruguay remains unsolved.

“There has always been a great deal of interest in literature and authors in this region since colonial times,” said Roberto Vega, owner of the Hilario bookstore and auction house. “Somehow, the manuscript ended up with this family. Before he died, the man told them he had an important original, but never mentioned the author’s name. They thought it could be [Jorge Luis] Borges, but didn’t find anything. The man had a lot of material in his library and in boxes. And guess what? At the bottom of one of the boxes, there was this folder. It could have easily ended up in the trash… but luckily, some cronopio stepped in so the owner’s son would stumble upon it.”

“It’s fairly common to discover unpublished material by lesser authors,” said Vega. “But not something by Cortázar — it’s a real find.” Both Vega and Aquilanti are optimistic that either the Argentine National Library or another such institution will be able to buy the manuscript. Aquilanti firmly believes that it should come back to the city from where Cortázar was exiled. “Even though Borges has written extensively about Buenos Aires and will forever remain our brightest literary light, this city is and will always be a cronopia,” he said. “People here actually read a lot more Cortázar than Borges. Just look at the sales numbers in local bookstores. I think we kind of admire Borges more than we truly love him, whereas with Cortázar, it’s both admiration and love. You can see Cortázar everywhere — monuments, graffiti, and even on the T-shirts of young and old people alike.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.