Nick Cave: ‘I don’t know where I would be if my son hadn’t died. Grief turns you into a person. Before, I was incomplete’

The Australian singer has lost two children and many friends and family members in recent years. But he has emerged stronger. He expresses this resilience in an album full of hope, titled ‘Wild God’

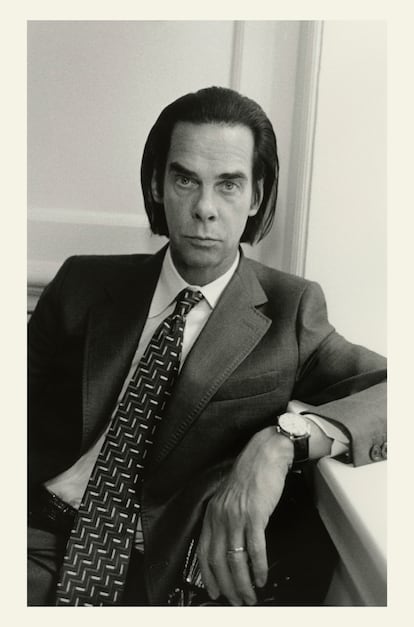

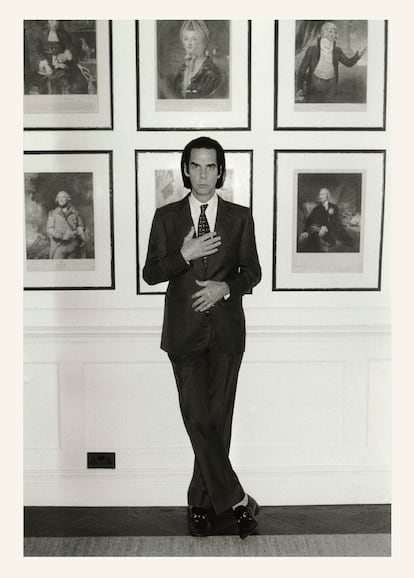

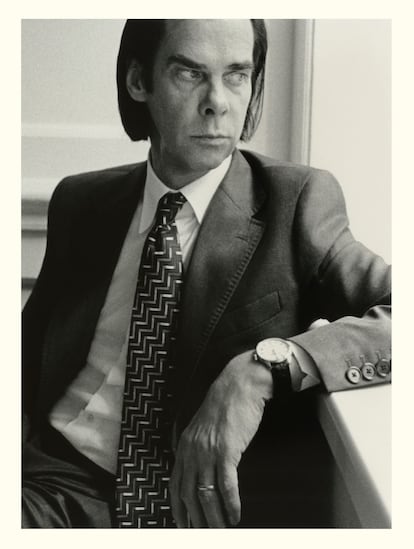

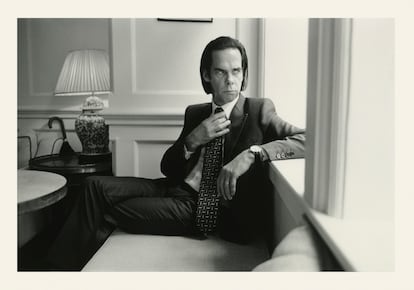

It’s impressive to be in the presence of Nick Cave. The wild Australian, the fiercest of punks, the reborn junkie, the crooner who came out of hell… the man who eats journalists for breakfast.

“Is that what they say about me? Well, it’s good to know,” the 66-year-old musician shrugs, with a half-smile.

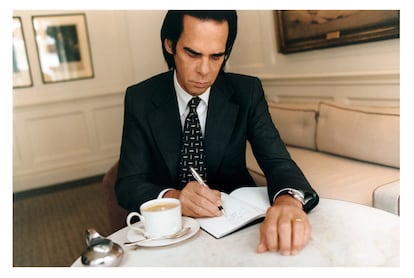

The first thing you read in his book Faith, Hope and Carnage (2022) is that he hates interviews. Cave smiles again: “Now I like them, because I enjoy a good conversation. My problem was that terrible situation [back then]. Whenever I sat down with a rock journalist, I knew what we were going to talk about: the new album, or the next tour. They would get bored and so would I,” he explains, delicately spreading butter on his croissant. During his interview with EL PAÍS — which takes place at a luxury London hotel — he eats his breakfast. He has lived in the UK for decades.

The Labour Party recently won a majority in the House of Commons. Is Cave interested in politics?

“A lot,” he nods, “or at least about what’s happening on the international stage. But from a relatively neutral point of view, I would say. People don’t like it, but that’s the way I am. It’s not even a political stance. I may be a terrible moral failure, but I have no real convictions in that sense.”

He turns 67 on September 20, but he looks 10 years younger. He is tanned, tall, thin, with incredibly blue eyes and dyed black hair, carefully combed back. He wears one of the tailored suits made for him by his friend — the designer Bella Freud — and wears a wedding ring, watch and pressed shirt. Cave is an uncanny version of the perfect English gentleman.

This past August 31, Cave released Wild God. It’s his 18th studio album with his band, The Bad Seeds. And this year is the 40th anniversary of Nick Cave first putting out an album under his own name. Before that, he was the frontman of The Birthday Party, a group with which he earned a terrible reputation. He could have succumbed to his vices, but behind that mask was a steely determination: while the stars of his generation became inconsequential, his fame just kept growing.

In the 1980s — turning the concept of the crooner on its head — he became a cult musician. Cave — who adores Elvis Presley — became a twisted and perverse version of the romantic singers of the 1960s, with their baritone voices. More than Sinatra, he reminds us of a possessed Dean Martin. Nobody can resist him.

His personality is such that, decades ago, he was able to record versions of classic country music — a genre that was despised at the time — and redeem it for the punk public. And, in the 1990s — during the heyday of alternative rock— is when he became a star. That was his glorious decade: he and The Bad Seeds put out hit songs like Stagger Lee, Where The Wild Roses Grow (an unexpected duet with Kylie Minogue), Into My Arms, or Red Right Hand. The latter allowed him to be discovered by younger generations, thanks to the Peaky Blinders TV series.

Nick Cave is still at the top. If his rise was unexpected, it’s even more admirable that he’s never come down. Today, he’s an Australian national treasure — a world-renowned musician and a pop phenomenon. He releases books, records and singles. And everything he touches sells, whether it be tickets for his tour, or the ceramics he made during the pandemic. He crafted and painted 17 figurines, which tell the life of the Devil in the style of the artisans from Staffordshire, in the Victorian era. “I didn’t think I would sell them… but Xavier Hufkens, the famous Belgian dealer, loved them. He became my agent and [collectors] buy them from him at very high prices. I’m not complaining,” he says with satisfaction.

The wild years are over. On stage, Cave used to be a beast with a killer’s gaze. His audience admired him because nothing seemed to bother him too much. He cultivated an image of a surly, impulsive rocker, always ready to crowdsurf. One of those guys you’d rather not turn your back on.

Cave has described his younger self as “an egomaniac,” with “low self-esteem and a huge sexual drive.”

“That’s true,” he acknowledges. “I was like that. And I loved being like that. All I cared about was having a good time. I also had the drive to do something important. I believed in myself to an inordinate extent, even though — in those days — there was nothing to suggest that I had anything valuable to offer the world. But I’ve changed.”

Heroin gives you a more orderly existence. I would say it’s more conservative. The conservative craves systems, order, that kind of thing

The version of Nick Cave who’s having breakfast with EL PAÍS was born on July 14, 2015.

On that day, his 15-year-old son Arthur — one of the twins he had with his wife, the designer Susie Cave — died after falling off a cliff in Brighton, where the entire family lived. The fall triggered a profound transformation. “I don’t know where I would be if Arthur hadn’t died. I say this very cautiously, but I think it’s grief that really makes you a person. I was [incomplete] before Arthur died. I was very different. Now, I see things clearly.”

“Back then, life was something that just happened. I didn’t really even pay much attention to it. But the value of life — once we started to get over Arthur’s death — changed. I now see the world as [deeply] beautiful and people as extraordinary, resilient and vulnerable creatures. My relationship to the universe has changed completely because Arthur died. I admit that if I could make some kind of cosmic deal and go back to my old life, I would… but unfortunately, those kinds of deals aren’t possible.”

Since then, death hasn’t stopped haunting him. In 2022, Jethro — the eldest of his four children — was found dead in Melbourne. He was a 31-year-old model who suffered from schizophrenia. Cave doesn’t talk about him because his mother — former model Beau Lazenby — asked him not to. Father and son didn’t meet until the latter was seven-years-old. When he was born, Cave was living in São Paulo with his then-partner and his son, Luke.

Cave has lost good friends, such as Mark E. Smith, from The Fall, or Shane McGowan, from The Pogues. He performed at McGowan’s funeral. And he has also suffered from the loss of two of the most important people in his life: his mother — to whom he always turned in his darkest moments — and Anita Lane, his first girlfriend, the inspiration (and possibly the creator) of the young Nick Cave. He dedicates a beautiful song to Lane on the new album: O Wow O Wow (How Wonderful She Is). “Anita was an extraordinarily talented human being. When punk rock came to Melbourne, she brought a group of people together and Anita was, by far — in everyone’s eyes — the brightest and the most intelligent. She worked very hard, but she was different from me: she didn’t have the need to show it to the world. She said that the best ideas are those that nobody sees. I despaired; I thought it was a terrible waste of her talent. I don’t believe that anymore.”

Since 2015, all of Nick Cave’s works — and that includes The Red Hand Files, the website he opened to answer his fans’ questions (he has received 10,000 so far) — speak of death, pain, mourning, guilt… and now, finally, hope. Wild God is the fourth studio album he’s released since Arthur’s death. The previous one — Carnage — was made with his right-hand man, Warren Ellis. The other three albums he was involved with over the past decade were recorded with The Bad Seeds — his band — and seem to form a trilogy: Arthur’s trilogy. It begins in 2016 with the cold and hollow Skeleton Tree — a zombie-like album — and continues in 2019 with Ghosteen, a beautiful attempt to invoke the spirit of his dead son. The trilogy concludes with Wild God, an exuberant, grandiose, lyrical album, full of almost religious choirs. It’s an ode to life… the album of someone trying to start over.

“You’re partly right, but it wasn’t planned,” he replies, upon hearing this description of his recent work. “When we record, we have no control over the outcome. I admit that Skeleton Tree is empty. It’s not that it doesn’t have good songs, but something fundamental is missing there. When I made Ghosteen, I had gone mad with grief. But I see Wild God as a joyful album. The very idea of Nick Cave making a joyful record is quite hard to believe, don’t you think? It’s been a long and radical journey, but I feel I’ve arrived at my destination without compromising authenticity. Does that make sense?”

I’m afraid I’m a believer for atheists and an atheist for believers. Religion is — for me — a structure and a system. I see it [as being] very similar to my work habits, which are very structured… but all kinds of things happen inside. They hold me down, but [these routines] also encourage my imagination

It does. From the start, Nick Cave was anything but cheerful. He has been dirty, angry, loud and cynical. A bad guy, charismatic and sexual. And a drug addict. He tried heroin in Melbourne in 1980, months before moving to London at the age of 22. He wouldn’t give it up for good until he was well into his 40s. “To a certain extent, heroin — apart from the wonderful feeling it gives you at the beginning — is a kind of strange device that brings order to your existence. Part of human tragedy is figuring out what to do with your life. A lot of people don’t know how to live it. But a heroin addict doesn’t have that problem: a junkie wakes up in the morning and the only option is to get high, otherwise the whole world would be thrown into chaos. He has to go for his fix. And he needs to do that twice a day. In a way, it’s a form of order. That’s why, when he quits, a drug addict’s life becomes a hell. He’s removing that order. That’s what I liked.”

“When I was on other drugs, it wasn’t the same. When I was living in Brazil, they didn’t have heroin, only cocaine, which is a messy, nasty drug. I fucking hate it. I used to take it all the time, but it’s a terrible drug. Alcohol is also a messy drug. As soon as you get drunk, you don’t know what’s going to happen. The terrible thing about being an alcoholic — which I was — is that it doesn’t matter what you did the night before. You could have jumped into a lake and saved a drowning baby. But you wake up in the morning feeling guilty. It’s a terrible thing. Heroin gives you a more orderly existence. I would say it’s more conservative. The conservative craves systems, order, that kind of thing. I think I’m essentially that kind of person. By the way, when I talk about drugs like that, I’m not promoting them… I had a few very good years using them, but I also wasted a lot of time. And [I experienced] terrible situations.”

It’s surprising to hear Cave define himself as a conservative.

“I don’t mean ‘conservative’ from a political point of view,” he chuckles. “It’s more a trait of my temperament. I guess I’m what they call a ‘small-c conservative.’ Someone with a fundamental understanding of the nature of loss, who understands that it’s much easier to tear something down than to rebuild it. I think a lot of people’s default setting is to tear everything down. To think that the system doesn’t work and that it needs to be destroyed. I don’t see it that way. I think there are big problems in the world that we need to approach cautiously. Let’s just say that I don’t have a naturally radical temperament.”

His past works give off some of this temperament. You can see, for example, how his relationship with God has changed. Cave has always used Christian imagery in his work: in his songs, there are quotes from the Gospel, demons, martyrs, heavenly fire... but, more than a believer, he seems fascinated with biblical folklore. And, in the eternal battle between good and evil, he seems to be on the side of the fallen angel. He used to be the rock version of the sinister preacher from The Night of the Hunter (1955). Yes, he prayed in his songs, but they were defiant prayers to a furious God.

After Arthur’s death, this all changed. The musician now needs answers and expresses his doubts with something he had never shown before: humility.

That I take advantage of other people’s talents is a popular narrative among some in Australia. Most of [the people who accuse me of that] are not artists, so they have no idea what it means to be one. Being an artist, in my opinion, is about collaborating and exchanging ideas. And that’s what I do

Raised as an Anglican in a non-practicing home, he isn’t interested in spirituality — something he considers diffuse and generic — but in religion. He sees the difference very clearly: “Religion is spirituality with rigor. And not just any religion: Christianity,” he claims.

The problem is that his lyrics — which used to tell stories — are now more abstract. For example, it’s not clear who or what this “Wild God” is in the title of his new album. “For me… I can’t even believe I’m talking about this, but for me, the concept of God isn’t that of a being who’s outside the world, who cannot change, who knows everything, who looks at the world with contempt and turns us into dancing puppets. I believe that God is embedded in the world and in his creations: human beings. That means that he isn’t static; he’s an ongoing project that grows with us,” Cave explains. “I think God suffers. And my character in Wild God is a human being who also suffers, [he’s] looking for the same thing as everyone else: someone who believes in him. I think we long for that much more than something to believe in. What we human beings want is for someone to sit in front of us, look at us and believe in us. Do you understand?”

Certainly. But when Cave says that the rigor of religion is what attracts him — with all the rules that such a practice implies — it’s unclear which sect he fits into. Is he a member of any congregation?

“No. I’m afraid I’m a believer for atheists and an atheist for believers,” he sighs. “I go back to the idea of ‘conservative.’ Religion is — for me — a structure and a system. I see it [as being] very similar to my work habits, which are very structured… but all kinds of things happen inside. They hold me down, but [these routines] also encourage my imagination. That’s how I see churches. For me, they’re man-made structures, dedicated to a certain kind of liberation: there, you can give yourself over to absolute sadness or absolute joy. You can vent feelings that we have no way of expressing adequately in secular society. There are things I feel in a church that I have no way of expressing outside… except maybe in music.”

“But I’m full of doubts,” he clarifies. “What I know is that, when I think everything is ridiculous, I don’t read Christian texts. I go to Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, or Dan Dennet, the great militant atheists. And when I hear them talk about their belief system, I don’t identify with any of it. That’s not me. I may not be a very good believer and I may be plagued by doubts, but I’m not an atheist. I know that deep down. I would say that, rather than being a Christian, I’m a lapsed atheist. If I’m not an atheist, it’s because I approach life in a poetic way and people like Dawkins approach it in a rational way. I don’t do that. I never have.”

“I don’t know if God exists. I don’t know if Jesus Christ died for our sins. [But] I do know that sometimes, when I’m in church, I feel an emotional attachment that… somehow, things start to make sense to me. My religious nature is in a constant struggle against my rational self.”

When asked if these feelings only arose after Arthur’s death, Cave firmly says: “No. Religion has been with me even in my most chaotic moments. When I lived in [West] Berlin, I didn’t go to church much because of the language [barrier], but I read the Bible a lot.”

Berlin is where Nick Cave became a soloist with The Bad Seeds. He arrived by chance. In 1980, The Boys Next Door — the Australian band he led at the time, which dissolved in 1983 — decided to try their luck in London. On the plane, they changed their name… and when they landed, they were The Birthday Party. But the experience was disastrous. The critics recognized the value of their furious gothic post-punk style, but not the general public. They were seen as too extreme: a bunch of ruined savages who, if they were lucky, slept on the floor of a squat house. So, in 1982, the group decided to move to the city of misfits. A place where heroin was plentiful, flats were cheap and people lived as if every day could be their last: West Berlin. “It was an absolute privilege to be there at the time,” Cave reflects today. “It was a kind of belle époque, but darker and more underground. Everyone was an artist of some kind. We shared ideas. We drank in the same bars, non-stop. And it was all fueled by very strong amphetamines. It was extraordinary. Chaotic, but creative.”

Two years after the move, The Birthday Party broke up. Or rather, the creative alliance between Nick Cave and the other composer — Rowland S. Howard — was no more. The topic is murky terrain: Cave is more of a singer and lyricist than a musician and has always needed a counterpart. He’s been accused of draining his creative partners and then abandoning them. Howard didn’t fit in with his plans and it’s said that, when Cave told him that he was out of the band, he was devastated, unable to understand why.

“That I take advantage of other people’s talents is a popular narrative among some in Australia,” Cave notes. “Most of [the people who accuse me of that] are not artists, so they have no idea what it means to be one. Being an artist, in my opinion, is about collaborating and exchanging ideas. And that’s what I do. Not only do I not think it’s bad: one of the things I’m most proud of in my career is that we’ve had long and very creative relationships that have lasted for years and have benefited us both. In Rowland’s case, it makes no sense to say that I stole his ideas. What ideas? The big difference between us was that I don’t have a depressive personality. I’ve never been depressed a day in my life. And Rowland was. He was an extraordinarily sensitive and easily hurt person.”

I’m not a particularly resilient person. I may look like one, but I’m afraid of being swallowed up by tragedy

Cave replaced Rowland with the German musician Blixa Bargeld, whose unpredictable guitar skills gave the band the anarchist edge that made it stand out, until he left in 2003. His place was taken by Mick Harvey, the last of the musicians who accompanied Cave from Melbourne. That’s when the band’s tune turned to a more classic rock and roll. Harvey departed in 2009 — also very angry — and, ever since then, Nick Cave’s partner is another Australian, the multi-instrumentalist Warren Ellis.

“With Warren, everything changed. When Mick left, he took his guitar with him… and we were glad to get rid of that instrument. It bored us, because he turned everything into rock. I had already made many records like that and [the change] pushed us in a more abstract, more atmospheric direction. But I think that — even though the guitar hasn’t returned — in Wild God, it’s The Bad Seeds. [The album] has an energy that takes me back to what we once were, without having to repeat things from the past.”

His rapport with Ellis is so deep that there was a time when he didn’t seem to need the rest of The Bad Seeds. He himself admits that he left them out of his previous albums. “We tried, but it just didn’t work out. Every time the drums played, something was lost,” he recalls. Perhaps, before 2015, he would have made a drastic decision… but the Nick Cave of today is different. He became a grandfather a few months ago and, every morning, he bathes in ice-cold water. “I just came back from Iceland… the Atlantic there is really cold. Jumping into that ocean as soon as you wake up is no joke,” he warns.

The musician has experienced loss and its consequences, including his wife’s depression. “I was very scared by what happened to my wife. The death of our son put our relationship to the test. It has been tested in every possible way and we have come out with a very particular bond, built on love and catastrophe. We’re very, very careful with each other. We know how vulnerable we are. If we argue, we sort it out quickly. We don’t allow any bad blood [to fester],” he explains.

Cave’s frankness in delving into his traumas is admirable. “Look, I’m not a particularly resilient person. I may look like one, but I’m afraid of being swallowed up by tragedy. A lady recently called my wife. Her son died five years ago and she didn’t know what to do, because she and her husband hadn’t spoken a word about it yet. That’s the other alternative: grief can be absolutely soul-destroying. You need to look at the world and be able to see it as something that leans toward goodness.”

When asked how he’s doing now, Cave sounds positive. “Generally, pretty good. Things are going well. Work is good. My relationship with my wife, good. My kids, good. My friends, good. And the world is screwed up.”

Recently, he wrote on social media that he’s not one of those people who wake up happy in the morning. When he’s reminded of this, he shrugs. “Well, I’m sure there are a lot of people in the world who wake up a lot worse than me.”

Puedes seguir ICON en Facebook, X, Instagram,o suscribirte aquí a la Newsletter.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.