‘Higgs Boson Blues’: between science and pop culture

In order to define the Higgs field, it was necessary to find the associated particle, also known popularly as the Holy Grail of the quantum world, the secret melody or the particle of God

If there is one certainty regarding the Higgs boson, it is that this particle lies somewhere between scientific communication and pop iconography.

As a matter of fact, there is a song by Nick Cave called Higgs Boson Blues. It is a sad sort of song, delivered in a broken voice, as if by a crooner of the dark; a song where the search and the journey are described in a tone that sounds more sinister than familiar. This gives some sense of the impact that the discovery of the Higgs boson had at the popular level.

But what is the Higgs boson?

The Higgs boson is an elementary particle relating to mass, a property without which the universe could not have been created. Scientific curiosity applied to the Higgs boson shows us that mass expresses the resistance formed by the Higgs quantum field. This field extends throughout the universe, and it is named after the physicist who discovered it, Peter Higgs. But let’s avoid confusion and start at the beginning, which is where everything begins, even songs.

We know that we are formed by atoms – not just us, but the entire universe. These atoms are in turn formed by subatomic particles known as fermions and bosons. While fermions make up solid matter, bosons are “force” particles tied to the forces of nature, that is to say, gravity, the electromagnetic force and the nuclear force, whether weak or strong.

One example of a boson is a photon, which is a particle associated with the electromagnetic field and lacking mass; this is the reason why it travels at the speed of light, unlike the so-called W-boson and Z-boson, which are associated to the weak nuclear force and which have a mass, meaning that they encounter resistance and travel more slowly.

This begs the question of why some particles have mass and others do not.

To answer this question, a theory was posited about a Higgs field whose associated particles have a mass. The photon lacks mass as it interacts with a different field, the electromagnetic one.

The conclusion was that the electromagnetic force and the weak nuclear force are engaged in a game of mirrors whose origin is presumably the electroweak force.

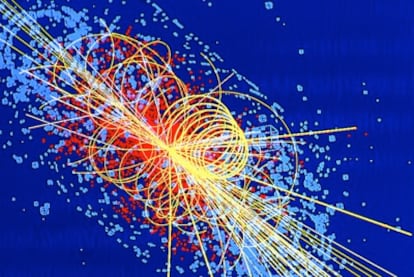

But in order to define the Higgs field, it was necessary to find its associated particle, which some people dubbed the Holy Grail of the quantum world and even “the particle of God.” This particle manifested itself on July 4, 2012 at the CERN Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the world’s largest and most powerful particle accelator, near Geneva.

From the moment in 1964 when Peter Higgs first theorized about how elementary particles got their mass, and up until the day when the particle showed itself in the LHC experiment, physicists followed trails across the invisible universe, letting themselves get carried away by a mix of uncertainty and experience until they reached a crossroads, haunted by a melody of dejection captured by Nick Cave as he drags his voice along a road made of dirt and other unidentified particles.

And so the scope of these particles’ reality extends beyond the realm of physics to reach pop culture, thus becoming a source of inspiration for works of art, such as a song.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.