Astrophysicist Heino Falcke: “There is a beginning and an end for our world”

The German scientist (and lay pastor) who led the team that took the first image of a black hole believes that science is unable to answer the big questions in life

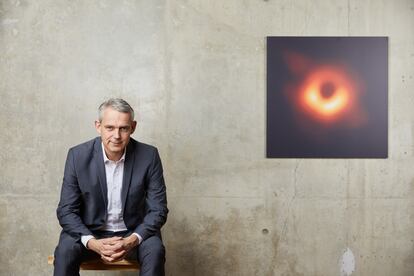

German astrophysicist Heino Falcke led one of the most ambitious scientific endeavours in history: producing the first image of a black hole. This required the simultaneous use of eight of Earth’s most powerful telescopes from Mexico to Spain to the South Pole, and €14 million in European funding. The image took two years to render under the weight of data to be processed. Falcke oversaw proceedings from the Pico Veleta telescope in the southern Spanish mountain range of Sierra Nevada in April 2017. There, he and his colleagues spent long nights snacking on “an enormous leg of jamón serrano,” he recalls. In the nearby city of Granada, processions for Easter were underway.

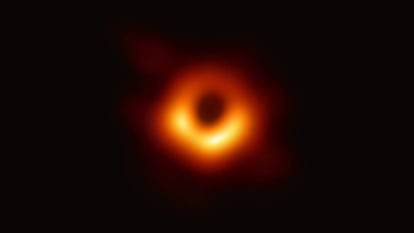

It was a fitting coincidence for a scientist who is also a Protestant pastor and deeply attached to his Christian faith. As the telescope gathered images from the black hole in the center of the Messier 87 galaxy, 55 million light years away, Falcke felt “happy, closer to the heavens,” he said. On April 10, 2019, his team unveiled the stunning image of the black hole to the world, and declared: “We have seen the gates of hell at the end of space and time.” Falcke, 55, is a professor of Astroparticle Physics and Radio Astronomy at Radboud University (The Netherlands) who has published a book, “Light in the Darkness,” about his life and work.

Question. What did you mean when you said you had seen the gates of hell?

Answer. Obviously they were not the gates of hell, but I like to use biblical analogies, because I grew up with them. The second reason is that I remember one of the biggest news stories when I was a young student was the discovery of cosmic microwave background radiation [afterglow radiation left over from the Big Bang.] The American astrophysicist George Smoot said at the press conference it was like seeing “the face of God.” The Big Bang is the beginning of space and time, while black holes are the end of space and time. I wanted something that would play against that idea of the face of God, and that’s why I talked about the gates of hell. I think it helped to capture people’s imagination. Black holes don’t only have a scientific meaning, but are also a kind of modern mythology, like dragons or those paintings of Dante’s inferno from the past. People see a black hole and they sense there is something beyond science.

Q. You speak in your book about the death of your mother, and link humanity and death to black holes.

A. Death is the final frontier for every human being, and black holes are also a final frontier. But as people, we don’t stop at that border. You think beyond death, even if you aren’t religious. We are afraid of these limits, but we force ourselves to think beyond them. Death is a terrible loss, but for some people it offers hope, and for Christians and in other religions death is not an end, but a beginning. As scientists, we think that at the edge of a black hole something new might happen, a new kind of physics.

Q. What is beyond the “gates of hell,” inside a black hole?

A. From what we know, automatic destruction. You can put an almost infinite quantity of matter inside a black hole. There are people who talk about “white holes,” through which you could enter other universes, but these are mathematical speculations and there is no proof they exist. I don’t think black holes are a door to another universe.

Q. You maintain that science is not the key to explaining the universe. You have even claimed that experimental sciences do not answer life’s big questions.

A. Has a particle accelerator ever answered one of life’s big questions? Science answers many questions and sharpens our minds. Experiments help us to better understand our universe and sometimes ourselves, but humanity is more than science experiments. You don’t think of yourself as a machine, but rather as someone who can think and feel in abstract terms. Physics doesn’t explain that. I don’t want to live in a world without science, but neither do I want to live in one where science is the only thing that counts. Hope, love and faith transcend science.

Q. As an astrophysicist and Christian, how do you envision the origin of the universe?

A. I think what science tells us: that there was a Big Bang and that evolution produced humans via natural laws, but that doesn’t tell us what caused the Big Bang. For me, the laws of nature come from God and are an expression of the Creator, just like ourselves. Our feelings and souls reflect something that already existed at the beginning.

Q. Earth’s destiny is to be devoured by the Sun. Do you think that our future extinction is God’s plan?

A. One of the crucial teachings of the Bible is that there is a beginning and an end, and that stands not only for our lives but also for our world. That’s where science ends and faith begins, because we hope to enter a new world and start a new life. We don’t know scientifically how it will work, but we don’t know how this all began either. The universe also seems unbelievable, but that exists, too.

“I don’t want to live in a world without science, but neither do I want to live in one where science is the only thing that counts. Hope, love and faith transcend science”

Q. You say in your book that if alien life forms were discovered, life on Earth wouldn’t change that much, and neither would religions. Do you think the Bible, Koran or Talmud make sense if there are alien civilisations out there?

A. Yes. The Bible is a long story about the experience of humans and God here on Earth. I believe the universe was created. If we discover aliens, I think that the first thing that we would want to do, as we have done in the past, is to send out missionaries to talk to them from a spiritual point of view. If we could speak with them we would learn a lot about the universe, but also about ourselves. I don’t think that would change who we are though, because our history on this planet would remain the same regardless of what is out there. I think they would also ask themselves if there is a Creator. In my book I write that discovering alien life forms would have little effect because we wouldn’t be able to speak with them: the distances involved are so large that we couldn’t have a conversation [not even with light speed signals]. This isn’t like Star Trek, where over the course of a few days they come and go. I don’t think our faith would change.

Q. In the book you also say it’s important to be a skeptic in science and in religion. Do you ever think “Maybe I am wrong and God doesn’t exist”?

A. Yes. When I won the Spinoza Prize, considered the Nobel of the Netherlands, I spent a day doing interviews with 10 different journalists and they all asked me “What? You’re Christian? And you don’t have any issues reconciling science and your faith?” They asked me 10 times and in the end I thought: “If everyone is asking me, could it be true?” There is nothing that I can prove to myself with 100% certainty, but faith is a decision: I want to believe and so I do. But my faith changes, of course. Not everything your pastor says is correct. You have to be skeptical. Maybe churches find themselves empty because they haven’t been sufficiently critical with themselves. The main rule is: love thy neighbour as thyself. Are we doing that?

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.