‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’ sweeps Japan after a 50-year delay

The 1967 novel by Gabriel García Márquez has become the publishing phenomenon of the summer in Japan, largely due to the upcoming release of the Netflix series based on the book

The Japanese paperback edition of One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967) has become the publishing phenomenon of the summer, selling some 290,000 copies in eight weeks… almost the same as the total number of three hardcover versions printed in the past 52 years.

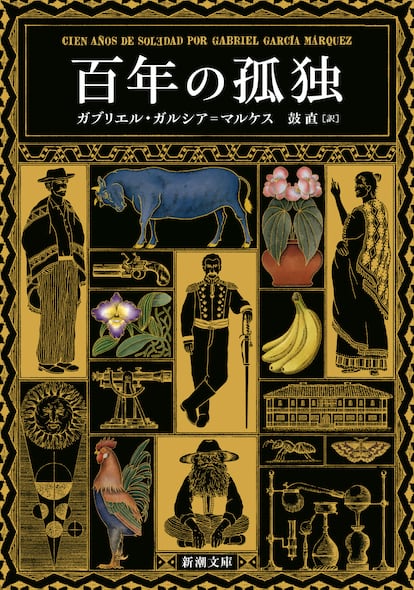

Among the reasons for the unexpected resurgence of Gabriel García Márquez’s masterpiece is the upcoming release of a Netflix series based on the novel. The work of magical realism has also influenced several prestigious Japanese authors, while the cover — displaying Macondo-like figures drawn in an encyclopedic style — is by one of the most sought-after local illustrators of the moment, Ryuto Miyake. He has led advertising campaigns for brands such as Gucci, Bottega Veneta, and Apple.

“In addition to offering it in a low-price format to readers who will watch the Netflix series, we wanted to take advantage of the 10th anniversary of Gabo’s death to re-introduce his literature,” explains Ryo Kikuchi, who is in charge of promoting the new edition of the novel. It was first released in Japan back in 1972, by the publishing house Shinchosha. At the time, the Colombian author hadn’t yet won the Nobel Prize in Literature… and Kikuchi hadn’t even been born.

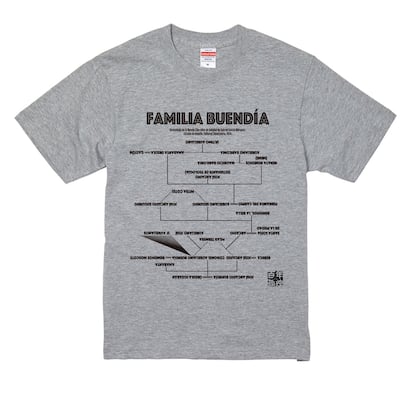

Kikuchi attends his interview with EL PAÍS while wearing a black t-shirt emblazoned with García Márquez’s smiling face. There’s also a yellow sign drawn on the shirt that reads “Welcome to Macondo” in Spanish. This is part of an advertising campaign that includes tote bags decorated with the Buendía family tree. The publisher clarifies that, despite the slow sales pace of the original edition, the novel has remained on shelves in Japanese bookstores all these years, given its reputation as a masterpiece of world literature. To date, One Hundred Years of Solitude has sold at least 50 million copies in 46 languages.

The novel, first published in 1967 in Buenos Aires, has also been a source of inspiration or a trigger for the literary career of distinguished Japanese authors. Kenzaburo Oé (1935-2023) — recipient of the 1994 Nobel Prize in Literature — was a declared admirer of One Hundred Years of Solitude, which influenced his 1979 novel, The Game of Contemporaneity. This is the story of an imaginary, peripheral town, whose founding myth symbolizes the modern history of Japan and questions the origins of the imperial family.

Another well-known Japanese writer, Natsuki Ikezawa, describes a fictional island in Micronesia ruled by a Macondo-inspired dictator in a novel titled The Navidad Incident: The Downfall of Matías (1993). Shortly after its publication, the book received the Tanizaki Prize, one of Japan’s major literary awards. Critics highlighted its stylistic break with the naturalistic and introverted novel, which had dominated Japanese narrative for more than half a century.

Ikezawa proudly (and jokingly) wears the label of “stalker of García Márquez’s prose.” At the first García Márquez Congress, held at the Cervantes Institute in Tokyo, in October of 2008, he explained that, by reading the Colombian author, he learned the technique of “defying the laws of cause and effect.” In a recent colloquium on One Hundred Years of Solitude, Ikezawa spoke with Tomoyuki Hoshino, another award-winning author, who, after reading the Buendía family saga in the 1990s, left the newspaper where he worked and went to study Spanish in Mexico.

During the discussion, Hoshino highlighted the novel’s relevance to the turbulent situation the world is going through, with social chaos, tyrants and wars, in a cyclical repetition of the story told by Úrsula Iguarán (the character who lives the longest in Gabo’s saga).

Many Japanese readers have picked up the pocket edition because they’re attracted to the cover by illustrator Ryuto Miyake. His style evokes the meticulous illustrations of the Botanical Expedition (1783), by José Celestino Mutis, who between the 18th and 19th centuries named and classified a large part of the Colombian flora. As in a collector’s display case, Miyake arranges 16 elements from the fictionalized town of Macondo, including a distilling apparatus, a telescope, a fighting cock and a bunch of bananas, as well as characters such as the Roma man Melquíades and Colonel Aureliano Buendía.

The orderly sequence of the drawings suggests the intention of guiding readers in a narrative that — according to comments on social media — is complex and difficult to follow. “Even though they’ve said that it sells like hot cakes, it’s not an easy book,” warns literary critic Sinsi Saito on his YouTube channel, while presenting a series of four educational episodes on One Hundred Years of Solitude. Saito breaks down the main events of the book, explains the origins of magical realism and recommends not questioning the logic of fantastic episodes, such as the flight of Remedios la Bella.

Commenting on the impact of One Hundred Years of Solitude, local Hispanists point out the quality of the first edition, which was undertaken by the late translator Tadashi Tsuzumi. This version was subsequently revised a couple of times for the two hardcover reissues.

The translated story of Macondo has a sensory layer that doesn’t exist in the original Spanish, thanks to the inexhaustible catalogue of Japanese onomatopoeia that — in addition to sounds — allow for the description of sensations or emotional states. In the opening scene, for example, the translator added the rhythmic sound of the stones in the Macondo riverbed (goro-goro) and, to convey its smooth feel, he used the onomatopoeia sube-sube.

The desire to better understand the novel has given rise to book clubs, with participants discussing both its literary and non-literary aspects. Personalities outside the literary world, such as comedian Baki Baki Virgin, with 1.6 million followers on YouTube, assure viewers that, despite its reputation as a masterpiece, it’s not a pretentious book. These Japanese influencers recommend enjoying the implausibility of its scenarios.

This advice is reminiscent of a witty suggestion by Kobo Abe — another famous writer and devotee of the novel — in a speech from 1983. After highlighting the “excessive seriousness” of his countrymen, Abe explained the properties of spicy food to stimulate the right hemisphere of the brain, where, according to the author, the sense of humor is located. Hence, he concluded that the best way for the Japanese to enjoy One Hundred Years of Solitude is to eat sushi with lots of wasabi.

Translated by Avik Jain Chatlani

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.