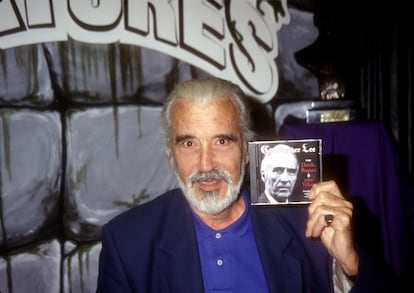

Nazi hunter, opera singer and Errol Flynn’s fight coordinator: The extraordinary life of Christopher Lee beyond Count Dracula

The documentary ‘The Life and Deaths of Christopher Lee’ reviews the biography of a movie legend who was dissatisfied with many of his films and whose experiences off set were, at times, more incredible than the roles he played on screen

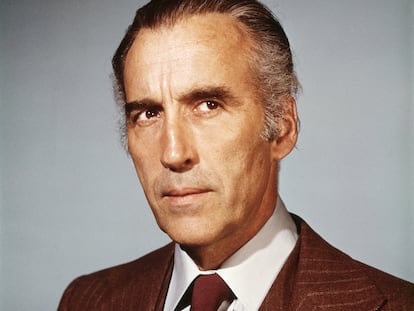

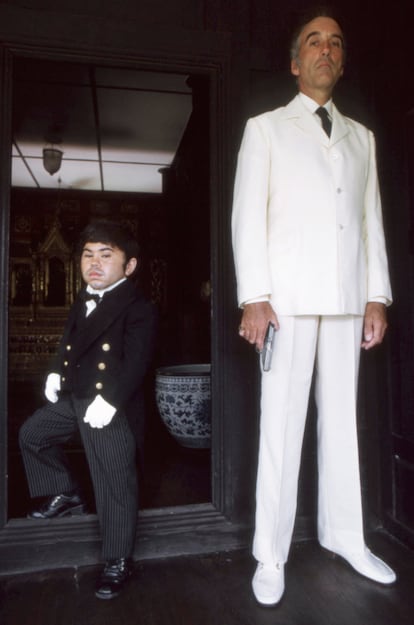

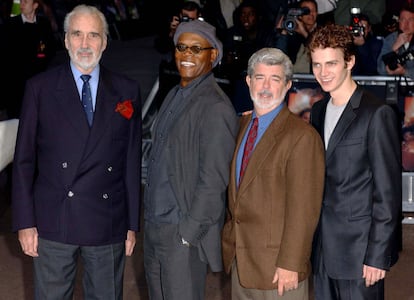

When Christopher Lee (1922-2015) was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 2009, the performer made it clear how he would like to be remembered. And, above all, how he would like not to be remembered. Asked by a reporter about the roles he was most proud of, Lee mentioned Count Dooku from Star Wars: Attack of the Clones (2002) ahead of Count Dracula, whom he officially played in 10 films. He also alluded to the drama Jinnah (1998), in which he played the founder of Pakistan, the villain Scaramanga from the James Bond installment The Man with the Golden Gun (1974), and the character of Saruman in The Lord of the Rings trilogy (2001-03), congratulating himself for managing to remain popular among different generations.

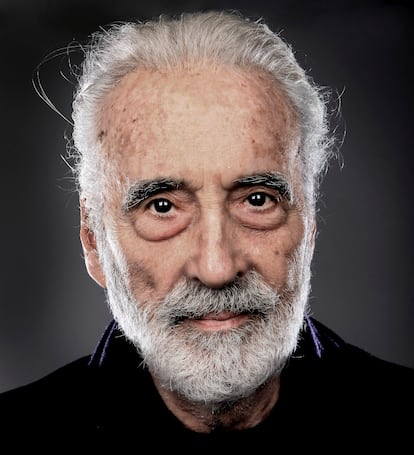

After his reply, the journalist thanked him, referring to him as “Christopher Lee, the king of horror,” a phrase that suddenly made Lee’s expression change: “Please don’t describe me as a ‘horror legend.’ I moved on from that.”

The interview footage has been rescued in the documentary The Life and Deaths of Christopher Lee, directed by Jon Spira, which has just been released through Movistar Plus+. The film can’t help but betray the actor’s desire not to be directly associated with the genre: with a sinister puppet representing him and a wealth of archival footage of the number of horror films he made (however much, in another interview for Photoplay, he unnerved fans by launching into a tirade that his only horror film was 1957′s The Curse of Frankenstein), Spira approaches Lee as the quintessential face of the British company Hammer Film Productions, playing characters for which, willingly or not, he carved a niche and a place in movie history. He was Dracula, he was the Mummy, he was Frankenstein’s monster and, beyond Hammer, he also played Fu Manchu five times, without this overshadowing his later successes, or vice versa.

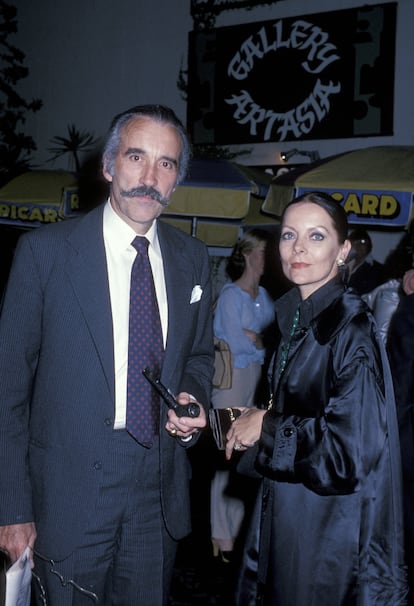

Lee’s biography, however, is sufficiently intense to underline that his more outlandish fictional characters did not impress him. The Life and Deaths of Christopher Lee is narrated by comedian Peter Serafinowicz, who imitates his voice as he recites excerpts from his memoirs. The son of a countess and a lieutenant colonel, his family on his mother’s side, the Carandini, were supposedly descended from Charlemagne. When they divorced, she married a banker distantly related to the Confederate General Robert E. Lee, who was also an uncle of Ian Fleming, the creator of James Bond.

As a child, through family relations, he met the assassins of Rasputin (whom he would play in the eponymous 1966 film) and also witnessed in France the execution of Eugen Weidmann, the last person to be guillotined in public. He also crossed paths with J.R.R. Tolkien. Although the element that has always aroused the most curiosity is his role during the Second World War, of which he hardly revealed anything under the cover of the official secrets act he signed.

He fought in the RAF and also collaborated with Italian partisans (among whom was his second uncle, Nicolò Carandini), a link through which it has been said that he made friends with Josip Broz Tito, who later became the leader of Yugoslavia. And he helped hunt down Nazi war criminals in special operations, a subject on which he also did not shed light. “He participated in numerous sabotage operations and worked with partisans behind enemy lines, as well as in targeted assassinations,” his friend John Landis, who directed him in The Stupids (1996) and Burke & Hare (2010), says in the documentary, although the filmmaker admits that even getting Lee drunk didn’t result in him revealing anything about his experience as a Nazi hunter.

Military history scholars have, however, questioned some accounts by Lee (who also claimed to have fought as a volunteer in Finland against the USSR as a minor), accusing him of magnifying his exploits or allowing others to do so by maintaining a self-serving silence.

In the filming of Saruman’s death for The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003), his discussion with Peter Jackson about how the character should die was, in that regard, much-talked about. “I seem to recall that I did say to Peter: ‘Have you any idea what kind of noise happens when somebody’s stabbed in the back? Because I do,’” Lee explained in an interview on the DVD extras. “He proceeded to talk about some very clandestine part of World War II,” Jackson recounted for his part. “He seemed to have expert knowledge of exactly the sort of noise that they make, so I didn’t push the subject any further.”

Dracula never dies

Spira’s film also dwells on Lee’s conflicted relationship with his work. While Peter Cushing, his eternal castmate (Cushing as the human, Lee as the monster), or his contemporary Vincent Price were comfortable and happy in their status as stars of the horror genre, the man who found in Dracula and Fu Manchu his particular Sisyphean works did not hide the dissatisfaction he felt with many of his films and envied the aura of prestige of Michael Caine.

“I told him I had seen all his films and he replied that he felt sorry for me,” director Joe Dante, who worked with Lee on Gremlins 2 (1990), recounts during the documentary. In 2007 — putting into perspective the determination with which Dante studied his idol — Lee was awarded the Guinness World Record as the actor with the most credited on-screen roles, for the 244 he had under his belt at the time.

Lee’s war wounds went beyond his crusades against the Nazis: he sported as a relic a scar from when Errol Flynn almost severed a finger from his right hand on the set of The Black Prince (1955). Experienced in fencing, in his early career he was employed to fight in adventure films with stars such as Flynn, Gregory Peck or Burt Lancaster, who were happy to be advised by Lee as they lacked expertise to make sword fights look realistic.

His participation in risky scenes also left him marked by the explosives and glass used in his confrontation with Cushing in The Mummy (1959) or the thorns in which he had to roll in the denouement of The Satanic Rites of Dracula (1973).

Lee — whose weariness and typecasting almost led him to a decline like that of his vampiric predecessor, Béla Lugosi (the Austro-Hungarian spent his career regretting not receiving the opportunities his rival, Boris Karloff, did) — was a pillar of the Hammer Horror factory in spite of himself. The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), the production company’s first film in color, forged a seal of identity that combined spectacular settings, violence, and a Gothic revival that would finally be cemented with Dracula (1958).

His performances were decisive in shaping the film series and the evolution of the genre. “You can’t understand the golden age of horror cinema in the 1960s without Lee’s presence,” Juan Manuel Corral, author of Christopher Lee: Beyond Horror (2013), tells EL PAÍS. “He was an indispensable piece in transforming the classic monster that decades earlier had been imposed by Universal’s black-and-white films, presenting more aggressive, bloody, sibylline and even erotic creatures.”

Corral doesn’t believe that Lee, aside from arguments with Hammer, refusals to recite unworthy dialogues — as in Dracula, Prince of Darkness (1966), where he doesn’t speak at all — or his refusals to play the Count again (often neutralized by the production company with the blackmail of reminding him how many people would be left without work because of him), detested horror.

“In reality, he loved the genre and what he despised was the attitude of the press that insisted on pigeonholing him. Leading B movies caused him financial problems for much of his career, and, therefore, when he settled in Hollywood and could enjoy a comfortable life, he turned his back on those cheap films to try to work on large commercial productions,” explains Corral. “He was an excellent actor of theatrical apprenticeship, capable of exploiting any register even with mime alone. For example, his characterizations as the Mummy or Rasputin for Hammer rely solely on his eerie eye movement.”

Far from being disturbed by the subject matter of his films, Lee explored the work of Satanist Aleister Crowley and claimed to own 12,000 occult books. He equally admired the original Dracula, Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel, and traveled to Spain to shoot a truly canonical adaptation, Count Dracula (1970), with the least canonical of filmmakers, Jess Franco (one of their seven collaborations).

During his fiscal exile in Europe, he worked with cult directors such as Franco, the Italian Mario Bava and even Pere Portabella, a great exponent of the Barcelona School, with whom he coincided in the unclassifiable Cuadecuc, vampir (1970) — a sort of experimental rendering of Count Dracula — and Umbracle (1972). The cinema of demolition and the avant-garde were not so far apart.

As a producer, he sought to update Hammer, and his bravery and desire to push the boundaries of the genre allowed for an unusual film like The Wicker Man (1973), which he considered his best horror work.

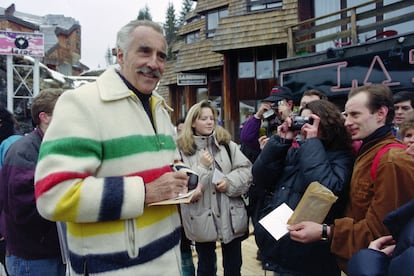

A Spanish son-in-law and heavy metal success

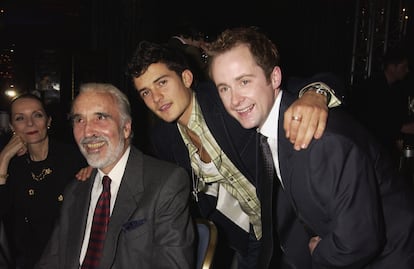

The renaissance of Christopher Lee in the final stages of his career was led by directors who had grown up admiring his films, such as Tim Burton, Peter Jackson, or George Lucas, which in turn led to an unprecedented status of recognition. It would not be his only late-life triumph: in 2013, at the age of 91, he became the oldest person to have a top 20 Billboard hit thanks to his heavy metal Christmas carol Jingle Hell. The Spaniard Juan Aneiros, husband to his daughter Christine and, also, his manager, personal assistant and record producer at that time, had a lot on his plate.

In 2003, Lee acknowledged his regret for not having devoted himself to opera, for which he felt he was born (he had a great-grandmother who was a soprano), but he was able to make up for it by singing on the symphonic metal Charlemagne albums (2010-13), dedicated to his presumed ancestor, and the EP of cover versions Metal Knight (2014), among other works.

Aneiros and his wife explain in The Life and Deaths of Christopher Lee that the performer was cast in The Lord of the Rings after asking his son-in-law to seek out the people in charge of production on the internet to tell them he wanted to appear. A fan of the novels, which he reread annually, the film he chose to watch on his deathbed in hospital was The Fellowship of the Ring (2001). Although the Briton had wanted to play Gandalf, Saruman found his way on to the podium of his most beloved characters among the more than 200 he played during his career. In the obituary published by EL PAÍS, animator Raúl García, who worked with Lee on Extraordinary Tales (2015), explained how the actor would sign autographs with a selection of three photos, depicting his roles in The Lord of the Rings, Star Wars and The Wicker Man. One absence significantly caught García’s attention: that of Count Dracula.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.