When 007 helped plot the invasion of Spain

As a spy in Gibraltar during World War II, James Bond creator Ian Fleming assisted with the drafting of a plan of attack by Allied forces in the event that Franco should help Nazi Germany

Following the 1940 defeat of the British and French forces by the Nazis in Norway, it was recognized that if the war was to be won, there was an urgent need for accurate, updated maps.

English pilots were unequipped with the vital information required to hit their targets, and many returned without dropping their bombs. The thousands of maps produced during World War I were obsolete, a fact that UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill was aware of.

Shortly before the British offensive to take control of Norway’s iron, Rear Admiral John H. Godfrey from the Naval Intelligence Department and his assistant Ian Fleming, who would go on to write the popular James Bond spy novels, got in touch with the prestigious geographer Kenneth Mason to help with the provision of up-to-date maps for the Allies.

Although Spain had little appetite for more war, the Allied forces were not convinced that Franco would not lend Hitler his support

New details were added, thanks to the efforts of spies and collaborators as well as images taken by the Royal Air Force Aerial Reconnaissance division. Further information was provided by British tourists who had been to Europe before the war, and who came forward with photographs in response to a public announcement by the British government on the BBC.

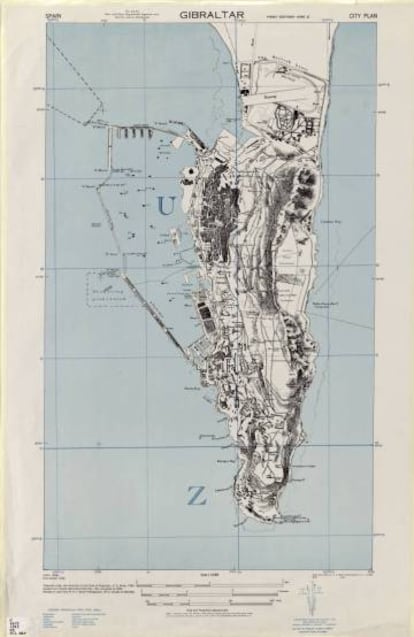

Regarding Spain, planes taking off from Gibraltar took photos and mapped the country’s main cities, particularly along the Mediterranean and south coasts, which had optimum strategic value.

Although Spain had little appetite for more war at that time, declaring itself neutral first, then non-belligerent, the Allied forces were not convinced that Franco would not lend Hitler his support in Operation Felix, a campaign designed by the Nazis to gain access to the Mediterranean by taking control of Gibraltar and North Africa, but which never took place.

To guarantee the success of 1942’s Operation Torch, the codename for the Anglo-American invasion of French North Africa that provided the second front requested by Stalin to relieve pressure on the Soviets, the Allied forces devised Operation Backbone with the aim of invading southern Spain and its Moroccan protectorate, though this scheme never came to fruition either.

Texas and Princeton

Many of the documents pertaining to this period have been declassified by the US in recent years and can be consulted at the University of Texas at Austin and at Princeton University in New Jersey. In fact, Fernando Sanz, a geography and history graduate who is now specializing in cartography and military history, came across an unusual map of his hometown of Valencia during his research. The map was dated 1943 and Sanz’s colleague, César Guardeño, found that there were copies at Princeton and Texas.

These were documents that had been drawn up in 1942 by the British intelligence service created by the legendary John H. Godfrey, who is thought to have inspired the character of “M”, James Bond’s boss in the 007 movies. Bond author Ian Fleming never concealed his admiration for Godfrey and used some of his traits for the creation of his fictional character.

Himself a spy, Fleming was stationed in Gibraltar to analyze the relationship between the Franco regime and the Nazis and to set up an operation to sabotage any alliance between Spain and Germany. That operation was dubbed Goldeneye, which is the title of the 17th Bond movie, released in 1995, and also the name of Fleming’s mansion in Jamaica where he penned his popular thrillers. A passport belonging to Fleming confirming his passage through Spain in 1941 was auctioned off in 2000.

“The map of Valencia was very interesting, very detailed, with well-marked objectives,” says Sanz. “It was sketched by hand with the old Rotring pens and contained details such as the sand on Nazaret beach, which no longer exists today. They even traced the passage of sand to the growing fields, as can be seen from the aerial photographs. It was a tactical map for the development of combat, shelling and bombing strategies; and it is very simple and clear, as the ISTD instructed,” Sanz adds alluding to the Inter-Services Topographical Department, created by Godfrey and overlooking the Inter-Services Intelligence Series.

In the lower left corner of the map, a note says that it is authored by the US Army but then goes on to explain it is actually a same-scale copy of an ISIS map. “There was an exchange of information between the British and American armies at the time,” explains Sanz.

Unsung heroes

The maps provided a wealth of information on Spanish cities, and they were classified as confidential, according to Sanz, who is soon to publish the research along with his colleague César Guardeño.

These researchers point out that the British classified the maps as confidential in order to protect their informers from Nazi or Francoist spies at a time when asking for a map in a bookshop could be regarded as suspicious. Not surprisingly, bookshops in Spain were run by sympathizers of the Franco regime in Spain, as were tobacconists.

Sanz also flags up the important work done behind the scenes by people who risked their lives providing information to complete the maps. “They are anonymous heroes,” he says.

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.