No money for David Lynch and no distributor for Francis Ford Coppola: Hollywood is no country for old men

Netflix has passed on funding one final project for the director of ‘Mulholland Drive,’ John Waters still has no financing for his, and ‘Megalopolis’ is trying to find a backer in the US

Billy Wilder died in 2002, but he had retired from directing a couple of decades earlier, in 1981, at the age of 75. His heart problems and unhealthy lifestyle meant that no company was willing to grant him the necessary insurance policy to continue working, so he devoted his senior days to collecting art, with the “bulimic enthusiasm” that he was no longer allowed to pour into cinema.

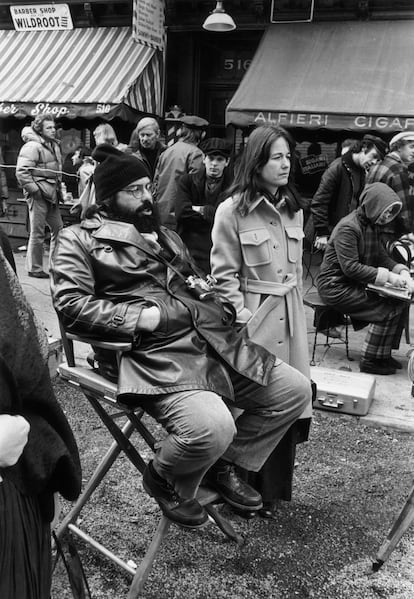

The New Hollywood generation, which revolutionized the seventh art back in the 1970s, has not encountered the same issue. Scorsese, Allen, Coppola, De Palma, Malick and Schrader still enjoy the rare privilege of continuing to make films at a very advanced age. Some of them, if the biological imperative permits, could beat the record of creative longevity set by Portuguese director Manoel de Oliveira, who announced he was taking a sabbatical at the age of 101, after the release of The Strange Case of Angelica (2010), and still had time to pick up the clapperboard again and direct another couple of films. The problem that the new batch of septuagenarians and octogenarians in Hollywood is encountering is that their films seem to arouse diminishing enthusiasm among both Gen Z audiences and the hierarchs of the industry.

Coppola has been the latest to encounter obstacles that could derail his career. Megalopolis, his first film in 13 years (since the failure of Twixt, an off-key, muted Coppola), took a while to find distribution in Europe and it still hasn’t in the U.S. It was of little use that the director of The Godfather poured $120 million of his own money, obtained by selling a large part of his Californian vineyards, into the movie. Self-financed and with a stellar cast, after 43 years of intermittent gestation, the film was presented at the end of March at a private screening for 300 people, and two months later at the Cannes Film Festival. At that screening it garnered polite applause, but no one, not Paramount, Disney, Netflix, Warner, or Sony, has been willing to bet their money on it.

At the same time, David Lynch, who is seven years younger than Coppola and is usually considered to be of the generation immediately after Coppola’s, has just been snubbed by Netflix, which will not invest a cent in Snootworld, the Blue Velvet director’s ambitious animated film. It served for little that Lynch enlisted Caroline Thompson, screenwriter of family film classics such as Edward Scissorhands or The Nightmare Before Christmas, for the project. The old-style fairytale that Lynch is putting together sounds to Netflix like a relic that is not worth gambling on. Lynch himself was also willing to leave the direction in the hands of his daughter Jennifer, the author of Boxing Helena and various episodes of series including American Horror Story and Gossip Girl. Whatever it takes for a project he describes as “extravagant and crazy” to have a chance of being made.

Another struggling veteran is John Waters, the sniper of scatology and (exquisite) bad taste who scandalized the world with such dunghill pearls as Pink Flamingos. Waters has announced that he is counting on actress Aubrey Plaza (The White Lotus) for a new project, Liarmouth, for which he only lacks the main thing: money. Waters takes his own novel, published in 2022, as a starting point to turn the chaotic adventures of Marsha Sprinkle, a white-collar thief, con artist and queen of disguises, into a film, a woman who is “intelligent, unhinged and not quite in her right mind,” hated by “dogs and children” and whom “her own family wants to see dead.” The most illustrious generator of cinematic detritus is now 78 years old and he has not directed a film for 20 years. Film critic Peter Debruge wonders in Variety what the hell Hollywood is waiting for to lend Waters the money he requires, now that cinema needs “his indecency and his lack of prejudice” more than ever.

Even Woody Allen, the 88-year-old author of 50 films, told Airmail magazine that he hasn’t ruled out his most recent movie, Coup de Chance, being his last. He claims to have new projects in the pipeline, but he is less and less willing to “go out and find the money to make them happen.” He finds it an embarrassing, if not humiliating, procedure: “If someone calls me with a proposal, I’d be happy to listen, but I’m too old to go begging from door to door.” Martin Scorsese (81), on the other hand, seems to be doing better than ever in the new ecosystem of content platforms. The filmmaker from Queens has been able to sell himself to the highest bidder (The Irishman to Netflix, Killers of the Flower Moon to Paramount and Apple TV+) and has been working at the healthy pace of a film every three to four years since the resounding career reboot that was The Wolf of Wall Street.

@francescascorsese The Muse @Oscar #fyp #martinscorsese #oscar #schnauzer #oscartheschnauzer #dadsoftiktok #leonardodicaprio #robertdeniro #margotrobbie #michellepfeiffer #ellenburstyn #paulnewman #muse #dogsoftiktok #doglover #acting #director

♬ original sound - Francesca

Scorsese has found in TikTok — a platform that his daughter Francesca introduced him to — an unusual shortcut to connect with the new generations. His casting of Oscar, the canine actor he presents as the legitimate heir to De Niro and DiCaprio, is a viral masterpiece. But his is an isolated case. For most of his contemporaries, as it is proving to be, Hollywood is no country for old men.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.