Elizabeth Horan, literary scholar: ‘Gabriela Mistral is as important for Latin America as Bolívar, Martí, or Mariátegui’

The American academic has published the first of three books dedicated to the Chilean poet, the only female Nobel Prize winner in the region and the first of the great writers to publicly identify as ‘mestiza’

Elizabeth Horan is 67 years old. But when you meet her, you get the feeling that you’re in the presence of a very young spirit. The literary scholar has the overwhelmingly energy typical of someone in their twenties — the period of time in life when the world is a sea of infinite possibilities.

She jumped into the depths of these waters when she traveled to Spain by herself in the 1980s, the years of the Movida movement, or when she decided to immerse herself in the bowels of Latin America after learning Spanish and Latin and reading everything she could find about Hispanic literature.

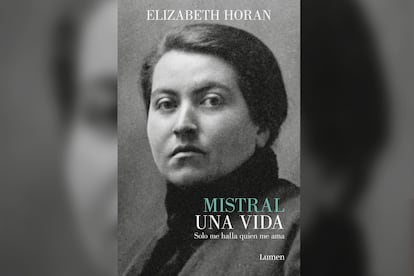

About 20 years ago, she began to investigate the character who she found to be the most fascinating: Gabriela Mistral, the Chilean poet, one of the first great writers of her region to publicly identify as mestiza (a person of both Spanish and Indigenous descent). And today — with those eyes that sparkle whenever she talks about her greatest passions — she has published the first of three books on the life of the poet, writer, professor and the only Latin American woman to have won the Nobel Prize in Literature: Mistral: A Life.

“Gabriela wrote letters. Many letters… too many letters,” says Horan on one of the pages in her book. Thanks to that — and to her enormous body of work, which hasn’t yet been fully explored or published — Horan was able to put together Mistral’s profile. She traced the Chilean poet’s journey from her birth, in 1889, in the small town of Vicuña, until the moment in which she left for Mexico, at the age of 33, to serve under Secretary of Public Education José Vasconcelos as he implemented his reforms. To do this, she had to pass several tests that Mexican diplomats gave her.

This was the first part of her life — a complex, uphill path to find a place in the Chilean teaching profession and, later, in her career as a diplomat. Mistral didn’t have it easy. She came from a lower-middle-class family that she ended up supporting with her teacher’s salary. She grew up in a female-supported household: all the women in her family knew how to read and write, at a time when only 10% of Chilean women could do so. Her sister and her mother did what they could to keep the house running, while Mistral joined the world that would give her new and better tools to survive.

In a letter to her wealthy friend Victoria Ocampo, she wrote: “Hardnesses, fanaticisms, ugliness… [these are the things] in me that you won’t be able to understand, being ignorant as you are about what it’s like to spend 30 years chewing raw stone with a woman’s gums.”

Hardness and ugliness took on every imaginable form in her childhood. The shadow of an alleged act of sexual abuse by a family friend (which took place when she was seven years old), her lack of desire to fulfill the roles imposed on her as a woman in a patriarchal society, and her extreme shyness all posed disadvantages. As did her sexual preference (she identified as queer) and her desire to explore the world beyond the valley where she was born. Despite all of this, she became the first female Latin American writer to win a Nobel Prize.

Horan, in her infinite enthusiasm, remembers asking herself how Lucila Godoy Alcagaya — Mistral’s real name — “came out of this valley without any of the privileges granted by a [famous] last name, which, in Chile, was everything? [And], without having any formal education after the age of 10, how did she reach the top of four professions at the international level?” After all, in addition to being a poet, teacher and diplomat, Mistral was a bold and prolific journalist. She “started in Coquimbo and published more than any other author of her time, when she was just a teenager. She wrote about 800 articles,” Horan recalls.

And how — as the academic asks in her book — did Mistral manage to carve out a space for herself in the global history of literature despite her “envious” detractors? Some called her a “third-rate scribbler,” such as the Spanish writer Pío Baroja, who, in 1946, just months after the Chilean received the Nobel Prize, criticized her by referring to her as the “cockatoo poet.” Jorge Luis Borges judged both her poetry and her articles poorly.

Being mestiza, a point of pride

Horan notes that Gabriela Mistral is the first and only great Latin American writer of the 20th century to declare her peasant origins and to describe herself as mestiza. “Given the racism that surrounded her, she didn’t openly assume this identity until shortly after her mother’s death. [Her mother was] the only authority to contradict her,” the academic says. “It must be said that the Chilean [literary environment] of the time was very racist. It’s enough to read the best-selling work by Nicolás Palacios (Chilean Race, published in 1904) or see the mortality figures among Indigenous peoples to understand why Mistral, in her Chilean era, barely referred directly to racial identity. However, if you look closely, she does do it… but in coded and metaphorical language, in the same way that she refers to her queerness and to her feminine masculinity,” Horan emphasizes.

After more than 20 years of studying, reviewing and rediscovering new writings and contributions by Mistral, Horan assures EL PAÍS that the Chilean’s place in history is still far from what she deserves. “Gabriela Mistral is an endless source [of knowledge] for Latin America. She forged a language that is totally her own and her prose is very accessible. She’s one of the first writers to think of Latin America as an entity. She hasn’t received the attention that she should have received: she is as important as [Simón] Bolívar, [José] Martí, or [José Carlos] Mariátegui.”

Secretaries and confidants

Horan’s book takes a journey through the Chilean woman’s life, looking at her work and the secrets guarded by her secretaries: the Chilean Laura Rodig, the Mexican Palma Guillén and the American Doris Dana. According to the academic, these women wove a meticulous and valuable network of collaborative work, which sought to provide Mistral with privileged positions in circles that were predominantly male. “Each book will be about her secretary at the time, or her primary secretary. This [first book] is about Laura Rodig. We know from letters that Rodig was a lesbian. While we don’t know with certainty that they were lovers, it’s possible. Mistral’s secretary-friend relationship has many connotations. The roles weren’t stable and had to be negotiated. This shows how sexual dissidence is a primary point [of interest].”

In her attempt to reach Mexico and work with Vasconcelos, Mistral had to go through several tests that a group of diplomats gave her, to demonstrate her ability to promote Mexico “not as a disorderly state in permanent revolution, but rather as a country that had diplomats, poets and very good poets. A country that was among the leaders of Latin America.” From there, her path was long, fruitful and transcendental. She was the architect of Vasconcelos’ educational reforms in Mexico and she was a diplomat and lecturer in a long list of countries, travelling around until the end of her life. Horan — convinced of the infinite legacy that she continues to discover in the Chilean writer — assures EL PAÍS that “Mistral was (as she herself observed) the last of her kind.”

Translated by Avik Jain Chatlani.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.