From Pancho Villa’s Japanese soldier to the Indian founder of the Communist Party: The forgotten stories of the Mexican Revolution

American historian Christina Heatherton presents a reassessment of the causes and effects of the first major revolution of the twentieth century within a global context

A man from Okinawa in the ranks of Pancho Villa’s army. It might sound made up, but it is the story he passed on to his son. At the time, many Okinawans were making the trip across the Pacific to escape Japanese imperialism — which ruled severely over their home islands and held a racist view of the locals — in the hopes of arriving in the promised land of California. However, xenophobia in the U.S. was never far away either, and at the turn of the century Asian migrants were barred from entering through American ports. However, bureaucratic obstacles rarely stop a determined migrant; many got off in Mexico, the ship’s next stop after California, to enter through the “back door.” On their way North from there, they encountered a country in the midst of Revolution, and saw how, in so many ways, the struggles of the Mexican peasantry were the same as theirs.

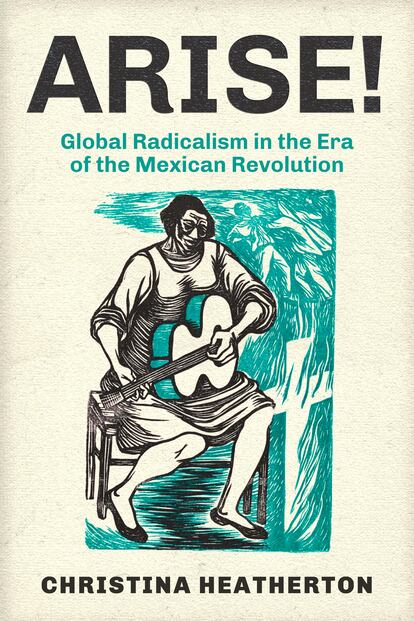

Historian Christina Heatherton stumbled upon this blurry and distant story of one of her ancestors, and she couldn’t shake off her curiosity to delve deeper. Through extensive research, which resulted in her book Arise! Global Radicalism in the Era of the Mexican Revolution, she learned that it wasn’t just Japanese migrants who developed a radical social consciousness in the whirlwind of the Mexican Revolution, but also people like M. N. Roy, an Indian revolutionary who arrived in the country in 1917 and swiftly founded the Mexican Communist Party, convinced that internationalism — the united global struggle against an oppressive, interconnected international system — was the way to bring about the socialist revolution to the whole world. Recovering and breathing new life into more or less forgotten stories like these, Heatherton places the Mexican Revolution within a global context. She traces its causes to the expanding American imperialist model and its consequences to a certain awakening of the lowest cogs in that developing global system. Heatherton’s reframing is a departure from how this story is usually told as an eminently local set of events — in the shadow of the Bolshevik revolution on the world stage — despite being the first great social movement of the twentieth century.

Yet, for Heatherton, the story begins many decades earlier. In 1848 to be exact. She is hardly the first person to identify this year as central in the history of social movements. After all, it was the year the Communist Manifesto was first published and when Western Europe was overcome by historic revolts. But Heatherton’s eyes are focused on the other side of the Atlantic. She posits that 1848 was also the moment when American capital imperialism — that is, the control of foreign lands through financial investment — was engendered, after the signing of the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which put an end to the Mexican-American war.

“[With the treaty] you have the U.S. seizing almost half of Mexico’s territory, which is a ‘traditional form of imperialism’ consisting of the seizure of land as a primary objective. But after 1848 Mexico becomes this key site for U.S. investment. By the outbreak of revolution in 1910, over a quarter of all U.S. investment lays in Mexico, U.S. financiers own 80% of all Mexican mineral rights, U.S. entities own more of Mexico’s surface than Mexican entities… It is in relation to Mexico that the U.S. develops the capacities with which it would come to superintend the global capitalist economy over the twentieth century,” Heatherton explains in an interview.

Anyone who has gone through the Mexican education system won’t recognize this story. Instead, what is traditionally taught is that the Revolution came as a result of three decades of Porfirio Díaz’s dictatorship — known as the Porfiriato — during which Mexico was modernized to an extent but at the high cost of extreme inequality, land accumulation and worker exploitation. This is not untrue. However, with Heatherton’s help the sequence of events gets completed, and we come to understand the defining influence that U.S. capital — and the ever-present threat of military intervention — had on the configuration of the Mexican state and institutions prior to 1910.

A similar blind spot exists when considering the impacts of the Mexican Revolution on the world stage. Very rarely is this event referenced as an influence on other social movements in different parts of the world. Even though it was the Soviet Union which centralized the idea of what a proletarian revolution was, Heatherton found evidence that, at the time, many foreigners who encountered and lived through the Mexican Revolution took with them invaluable lessons about solidarity, oppression, and the interconnectedness of the exploitation that defined the capitalist system. In other words, they discovered internationalism in the flesh.

This dynamic was very clear to see for one of those Okinawans who passed through Mexico on his way to the United States. His name was Paul Kochi, and in his memoirs, which Heatherton refers to in a section of her book, she identifies this nascent and unprecedented grassroots internationalism. However, in Arise! perhaps the best exponent of this new internationalism unwittingly forged in revolutionary Mexico is M. N. Roy.

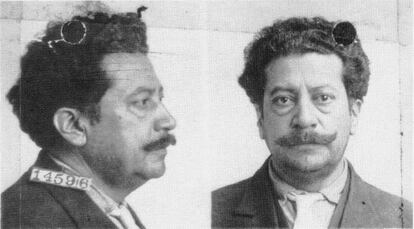

The Indian independence advocate left his home country in 1915 in search of arms for the national revolution and arrived in Mexico a couple of years later, after spending time in the United States. Shortly after this, he founded the Mexican Communist Party — the first outside Russia. In 1920, hereturned home with the conviction that the liberation of India “was no longer an end in itself, but a necessary step toward global revolution.” He considered the world capitalist system was built just as much on the subjugated peasants under — financial or traditional —colonial rule as on the backs of exploited industrial workers. Thanks to his ideas and influence, he was quickly named as a part of the Executive Committee of the Comintern by Lenin, in charge especially of preparing the East for revolution.

“Part of what I’m arguing is that by thinking about the convergence of all these different rebels — migrant workers, soldiers, artists —[and] by thinking about how they appraise the world, how they understood their situation, how they came to understand global struggles in dialogue with each other, you get this different trajectory of how you can think of internationalism […] Because the conditions that led to the Mexican Revolution were not unique to Mexico in the period, they just uniquely exploded to make way for the first major social revolution of the XX century,” says Heatherton, reinforcing her argument that internationalism in practice wasn’t a divine theory that is given to people, but rather an acquired consciousness.

As Heatherton traces the reverberations of the Mexican Revolution, she shifts her focus north of the border through the stories of various characters and places. One such storyline is Ricardo Flores Magon’s stay and eventual death in Leavenworth Penitentiary in Kansas, a prison used primarily to incarcerate political radicals of all types and which became, as she says, a “university of radicalism” largely influenced by the lessons of Mexican revolutionary veterans and peasants. Another is the organization of farmworkers in California in the late twenties and during the Great Depression, which carried the spirit of the Mexican Revolution since many of those farm hands had fought or at least lived through the revolution in the decade prior, whether they were Mexicans, Americans, or Japanese.

In a meticulously researched and vivid account of these and other stories, Heatherton weaves together the threads of a historical web that emanated from revolutionary Mexico, filling in crucial gaps and connecting diverse narratives. In doing so, the author shows how intellectual and racial prejudices, unwittingly reproduced by the hegemonic left, buried this international interpretation of the Mexican Revolution and reduced it, in the mainstream, to a romanticized image of Pancho Villas, Emiliano Zapata and masses of sombrero-wearing peasants — an endearingly wild episode that had little to teach the rest of the world. In this exhaustive historiographical and narrative exercise, Heatherton recovers it and places it, in terms of social and historical impact, in the pantheon of history’s great revolutions.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.