The long journey of Pancho Villa’s historic pistol

The 38-caliber revolver, manufactured in northern Spain in the early 20th century, was a gift to the revolutionary from former President Francisco I. Madero. Now it returns to Mexico after passing through Cuba

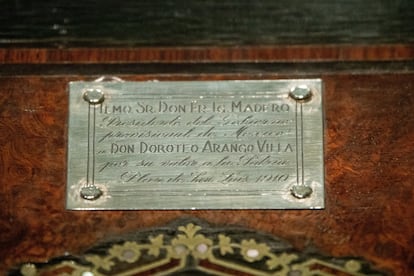

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador returned from Cuba with a pistol loaded with symbols. During his working tour of Havana, the Mexican president received from the hands of his Cuban counterpart, Miguel Díaz-Canel, a historic 38-caliber revolver as “a sign of the friendly relationship shared by both countries.” The steel and gold piece is now in the Revolución room of the exhibition La Grandeza de México at the National Museum of Anthropology. Its long journey began around 1910 in Eibar, in northern Spain, in an industrial city known for the manufacturing of iron, which gave rise to a thriving arms industry. The piece was gifted alongside two percussion bullet cartridges and a box made of wood, mother-of-pearl and silver, with a plaque inscribed with a dedication by the then-president of Mexico, Francisco I. Madero. It was a gift to the caudillo José Doroteo Arango, better known as Francisco Villa, “for his value to the Homeland.”

“This is a historical and artistic piece, but also an object that holds a diversity of meanings, starting with the relationship between the leader who started the Mexican Revolution and the caudillo whose role was vital in the development of the historical event,” explains Diego Prieto, director of the National Institute of Anthropology and History. The weapon ended up in the hands of Cuban historian Eusebio Leal Spengler, who acquired the pistol after it was speculated that it was brought to the island by a veteran revolutionary.

López Obrador often expresses a special admiration for Francisco I. Madero, imagining himself as the historical figure’s heir and successor. Enrique Krauze, who holds a PhD in History from the prestigious social sciences higher education center Colegio de México (Colmex), writes in his book Mexicanos eminentes (or Eminent Mexicans), “Francisco I. Madero was a kind of Mexican David who, despite his short stature, defeated the old and legendary Goliath Diaz. He is also the apostle sacrificed after the Tragic Decade. The idea that Mexico could be a democratic country could only fit in a soul as innocent as Maduro’s, but there was nothing innocent about that belief. To think that democracy in Mexico is a quixotic project, viable perhaps for the year 2347, is as false as maintaining that Madero’s middle name was Inocencio.”

To follow the weapon’s trail, we must travel back to 1872, when Alfred Nobel, who discovered dynamite, opened his first Spanish factory in the northern province of Vizcaya, in the Basque region. The region’s mining operations and its proximity to France and the commercial port of Bilbao led the Swedish inventor and a group of businessmen to start up La Dinamita, which gave rise to the Spanish Union of Explosives (UEE), the world’s third business group in the sector. Established in Bilbao, UEE achieved a monopoly in Spain in 1897. In 1911, it began manufacturing military explosives: gunpowder, trilite, tetralite and cartridges for the Spanish Ministry of Defense. They went on to integrate other factories, including the Spanish Arms and Ammunition Society of Eibar, in the province of Guipúzcoa, where the pistol that Francisco I. Madero later made for Pancho would be manufactured. The weapon was made by the Irióndo y Guisasola firm and adorned with yellow figures and blue details, as well as a “U” with a double royal crown as an inscription. In 1919, months after the end of World War I, Eibar’s arms factories entered a crisis. Orders ended and stock accumulated, but almost none of them closed. Beistegui Hermanos (BH), Garate Anitua and Orbea were transformed into bicycle factories, Olave y Solozabal went from rifles to office supplies and Alfa began to manufacture sewing machines.

“Pancho Villa and Francisco I. Madero always appreciated each other a lot. When the revolutionary troops entered Mexico City in December 1914, Villa went to mourn at the tomb where Madero had been buried. He couldn’t hold back his tears. Before that, Madero had saved Villa’s life. When that stage of the Revolution ended, Porfirio Díaz decided to leave the country, in 1911, and Pancho Villa joined the army fighting the rebels in northern Mexico. Victoriano Huerta always saw Villa as a ‘temporarily armed mob.’ They had orders from Díaz to shoot him. When the soldiers were about to shoot, Madero’s brother intervened. And he received a telegram from Francisco to spare Pancho Villa’s life,” the writer and historian Enrique Ortiz explains to EL PAÍS.

Villa llorando!!Rodolfo Fierro llevando un ramo de flores y más en este video del 8 de diciembre de 1914. En esa jornada el líder de la División del Norte visitó el Panteón Francés de la #CDMX para visitar la tumba del presidente Madero, asesinado por golpistas en febrero de 1913 pic.twitter.com/nIRNL6pwSm

— Tlatoani_Cuauhtemoc (@Cuauhtemoc_1521) May 22, 2022

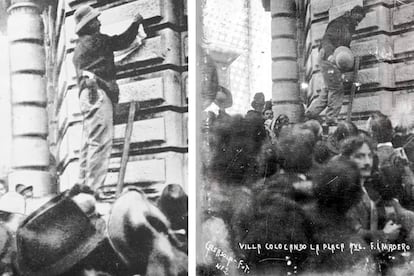

Another episode that shows the depth of their friendship occurred in December 1914. Pancho Villa changed the name of Calle de San Francisco, one of the most iconic streets of the Historic Center, to Calle de Francisco I. Madero. “The appreciation Villa had for Madero reached that degree during the revolutionary process. He climbed a ladder, took the plate and nailed the new one called Francisco I. Madero. Villa believed in the ideals of Madero himself. The Porfiriato plunged the population into poverty and only an elite group benefited. The Bellas Artes opera house, the Ministry of Communications, where the National Museum of Art is now housed, were all only for the cliques that governed the country, when more than 80% of the population lived in conditions of extreme poverty,” explains Ortiz.

The place where the gun was manufactured and the reason it arrived in Mexico is certain. The only mystery is how and when it arrived in Cuba. Some speculate that the weapon was brought to the island by a revolutionary veteran and then came into the hands of Eusebio Leal Spengler, a renowned historian from Havana, who died on July 31, 2020, at the age of 77. He held a PhD in Historical Sciences from the University of Havana and had received a master’s degree in Latin America, Caribbean and Cuban Studies. He was also a specialist in archaeology and did postgraduate studies on the restoration of historic centers in Italy. In addition, he was a great collector and admirer of Mexican culture.

In 2016, the Embassy of Mexico in Cuba offered a tribute to Dr. Eusebio Leal, recognizing his career and his work to promote Mexican culture in Cuba and to bring the Cuban and Mexican people closer together. Dr. Leal received the Mexican Order of the Aztec Eagle, the maximum distinction that Mexico grants to foreigners to recognize the services rendered to the Mexican Nation or to humanity. Leal Spengler also directed the Master Plan for the rehabilitation and restoration of the Historic Center of Havana. Last April, Leal’s son, Javier Spengler Estébanez, delivered the pistol to the Historian’s Office in Havana, requesting the express will of his father: “That the piece of cultural heritage be restored to the great Mexican nation.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.