The ‘Shirley card’ legacy of racial bias in photography

The advent of color film in the 1950s led to a standardized, color-balanced chemical development method based on a white model

In her 1977 book On Photography, Susan Sontag wrote that photos not only depict reality but also reflect the viewer’s perspective, thus serving as both a documentation and an interpretation of the world. Author James Baldwin added: “It is said that the camera cannot lie, but rarely do we allow it to do anything else, since the camera sees what you point it at: the camera sees what you want it to see.” Sontag foresaw in the seventies that today’s world would be flooded with images. This has become reality: the digital image overload led to a resurgence of analog photography, with sales tripling in 2023. Film development is reintroducing the concept of waiting, and its vintage colors are making a nostalgic comeback. Yet, underlying it all is a persistent grammar — an “ethics of vision” — highlighted by historian Luis Vives-Ferrándiz Sánchez in his book on contemporary visual culture. Chemical film developing processes were established within and for a society marked by racism. To fully understand this, you need to know the history of the “Shirley card” and how “normal color” shaped our perspectives.

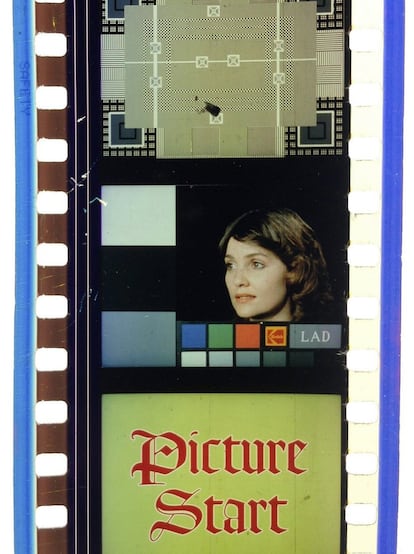

In the 1950s, the introduction of Technicolor transformed the world by bringing vibrant colors to screens. This innovation replaced black-and-white photography, making color photos accessible to the masses. You didn’t have to be a Hollywood star or wealthy socialite to get a portrait highlighting your green eyes... and light skin. However, this future excluded non-whites because Kodak standardized color photo processing with a card it distributed to labs worldwide. The card featured a portrait of an anonymous woman nicknamed Shirley, alongside samples of six different color tones, including the primary colors (red, yellow and cyan), as well as intermediate colors like pink, green and another shade of blue.

Also known as the “color photo girl,” the original Shirley — a white brunette — was dressed in white and wore a pearl necklace. Developed using a blend of the color tones on the card, Shirley had light-colored eyes and fair skin. Underneath her portrait was a label that said “normal.” Shirley set the standard for chemical film developing using machines calibrated to obtain the proper skin tone in prints. According to Sarah Lewis, an art history and architecture professor at Harvard University, the aim was to ensure all the Shirleys looked good in every photo. These calibrated cards were also used in film and TV, where Shirley was called “China Girl,” a reference to the porcelain mannequins used in early screen tests for makeup standards on sets.

In 2019 New York Times article, Lewis explained how this translated to color balancing in digital technology. For instance, the way camera sensors in automatic mode detect subjects influenced the development of video surveillance systems. MIT Media Lab’s Joy Buolamwini’s discovery that facial recognition algorithms do not see dark-skinned faces accurately is expertly explored in the award-winning Netflix documentary Coded Bias, directed by Shalini Kantayya.

The defect acts like a wild card but conceals a pattern in the original Shirley card and the variations that followed: a few men chose a bunch of women and blended them into one ideal. They first selected features like eyes, hair color, height, width and skin tone. Then came neckline styles, hairdos and clothing. And of course, always remember to smile. The outcome shaped our view of the world. Through the Shirley cards, Western ideals objectified the female body, turning the dominant societal perspective into reality for all. As photographer Laurent Leger Adame said, “Technology is supposed to level the playing field for everyone, but it’s created by us humans, and we all bring our own social norms into the mix.”

Leger, a person of color, deals with the everyday challenge of adjusting cameras to accurately capture darker skin tones. While digital cameras can be fine-tuned to represent dark skin well, the default settings are usually based on lighter skin tones, leading to overexposure of faces with darker tones. “So, you’ve got to decide if you want to prioritize making the person look good even if it affects the rest of the image, or take a chance on compromising their appearance for the sake of consistency.”

Nowadays, image editing on a computer allows for adjustments like increasing shadows and balancing contrast, even for digitally scanned analog photos. “Of course, it’s unfair because you end up spending more time on photos of certain people just because they’re Black.” Efforts to address the problem have been underway for some time. For instance, some professional photographers began using film made by Fujifilm in the late 20th century because it displayed dark skin tones more faithfully than Kodak film.

New approaches have also been explored in the realm of cinema. Cinematographer Bradford Young, known for collaborations with director Ava DuVernay, is always innovating lighting techniques for filming. Similarly, director of photography Ava Berkofsky shared her methods for lighting actors on the HBO series Insecure in a recent interview with Mic. Her top tip? Use a moisturizer on Black skin to get more reflections. But this technique has a problem that brings us back to the beginning of this story. “It can give faces a porcelain-like appearance,” said Leger, who’s not very enthusiastic about the technique.

People of color face a number of challenges achieving an accurate appearance on camera. “Film emulsions could have been designed initially with more sensitivity to the continuum of yellow, brown, and reddish skin tones, but the design process would have had to be motivated by a recognition of the need for an extended dynamic range,” wrote Lorna Roth, a media and communication studies researcher. Leger believes that this recognition should also encompass equipment, like lenses.

The lack of recognition left millions of people with overly dark photos that obscured their features. In a 2014 BuzzFeed article, Syreeta McFadden wrote, “Kodak never encountered a groundswell of complaints from African-Americans about their products. Many of us simply assumed the deficiencies of film emulsion performance reflected our inadequacies as photographers. Roth discovered that the Shirley card changed due to pressure in the 1970s from furniture and chocolate manufacturers to correct color bias. They complained that their print catalogs couldn’t accurately depict subtle details such as wood grains and chocolate shades. But making the change for people seemed impossible.

Nearly fifty years on, photographers still seek out the aesthetics of that bygone era. “I notice a lot of photographers these days who rely on old photos for inspiration when they take pictures of Black folks. I still see magazine pics of people with dark skin that are lighter than the original photos. This happens because they’re sticking to that old inspiration, using old film to match those pics. It’s just laziness and ends up making us look too dark,” said Leger. He says magazines and media outlets are now favoring professionals who work with analog equipment and chemically developed film. Leger prefers it “because the product of analog photography, technically speaking, is a whole different ballgame. It’s all about mastering the art.” He argues that the careful use of film enables more control over composition, which is often overlooked, especially by white photographers. Analog image quality has a charm of its own, even when its digitally emulated using software and app filters.

Instagram’s logo was designed to look like a Polaroid camera. Interestingly, the Polaroid ID2 model was used to photograph Black people for South Africa’s infamous passbooks, a tool of racial segregation and enforcement during the apartheid era. Syreeta McFadden noted that the ID2 has a flash boost button engineered to add 42% more light on its subjects. Its effect would result in a deliberate darkening of dark-skinned subjects. In a 2013 interview with The Guardian, South African artist Adam Broomberg said the light range was so narrow, that “if you exposed film for a white kid, the black kid sitting next to him would be rendered invisible except for the whites of his eyes and teeth. This goes along with what Leger is really worried about: more and more white photographers who deliberately “darken the person so you can only see their eyes, which is seriously offensive to us.”

“Who protects Black people? What about all the crossover we have to do? If we all disappeared, who would remember us?” asks Pica Sullivan, the protagonist of Drylongso, a 1998 film by African-American director Cauleen Smith. Pica was talking about the ongoing violence in Black communities caused by police brutality and drug overdoses. The film, shot with a 16mm camera, follows a young, Black art student from Oakland who takes picture of young people of color. Cauleen sees photography as a means to preserving individuals and communities, fearing their memory will fade. Ironically, the camera Pica uses is a Polaroid.

Four years before Drylongso, Kodak finally introduced a multiracial card with three women who were quickly dubbed “the new Shirleys.” It was intended to reconstruct the standard with different skin tones. But by then, digital photography was approaching to perpetuate a legacy the cards could not resolve. A month ago, Leger says, two girls came together to his studio so he could photograph them. One was of Congolese descent and the other Tunisian. “When I started taking their photos, the digital camera I was using accurately picked up details for one girl but not the other. So, I had to adjust the background and brighten the lighting a bit for the darker-skinned girl. ”But Leger insists, “If you know how to do it, it’ll just take a few extra minutes, so no excuses. Let’s use the same technology that shaped us to change things — but we have to be intentional about it.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.