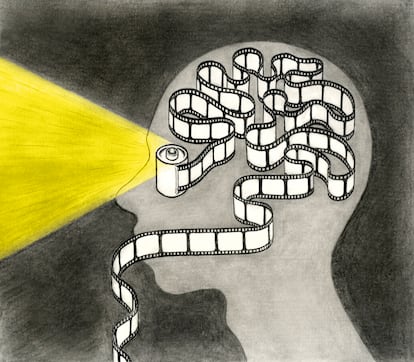

Why do we obsessively take pictures? Photography on the analyst’s couch

Immortalizing moments has become an essential part of experiencing them. But photographs have always been a border between the private and public self. And they are a useful tool for psychoanalysis

Photographs, like dreams, are loaded with unconscious meaning. My patients frequently bring photographs to their sessions. Take, for example, the image of the cat Puccini, who died some time ago. It didn’t just put a face to my patient’s grief at the loss of a 12-year relationship; it also gave us access to her feelings about other faraway but significant losses, which had gone unmentioned until her associations with the image brought them back. The click of a camera has become one of the main filters between ourselves and the environment. Thinking about photography through the lens of the unconscious can help us understand the optics that affect almost all aspects of contemporary life.

According to Freud, photography as a medium is associated with the psychic effects of trauma: the automation of the process, the open camera lens and the film’s sensitivity to light all play a part in that association. Just as the snapshot bypasses both intention and artistic convention, traumatic events bypass our consciousness. Both imply something external that leaves an indelible impression. As early as the 1930s, the philosopher and critic Walter Benjamin proposed that the camera revealed something he called the “optical unconscious.” Like latent memories, details in photographs come into focus and become visible. Benjamin describes them as “flashes.”

In addition to meeting their fate in a psychoanalyst’s office, these images traditionally ended up being relegated to a drawer or the confines of a family album. Those from long ago can be found in flea markets or museums, under the rubric of “vernacular photography.” Experts debate whether they can be considered art. Indeed, it is hard to see these brightly colored or silver gelatin rectangles, with their glossy smoothness and white edges, except through a distorted haze of nostalgia.

“Photographs alter and enlarge our notions of what is worth looking at and what we have a right to observe,” writes Susan Sontag in On Photography. She argues that photography gives us the feeling that we can contain the whole world in our heads, like an anthology of images. “By furnishing this already crowded world with a duplicate one of images, photography makes us feel that the world is more available than it really is,” Sontag says.

Perhaps the term “photography” is somewhat restrictive, especially in our age of smartphones, which invite anyone to take snapshots at any time, in ever-increasing quality. Even the distinction between snapshot and video has become blurred. And so, taking pictures has become one of the main ways to experience something and give the appearance of participation. The number of snapshots taken around the world each day is skyrocketing. By 2023, 54,400 photos are taken per second, a statistic that arguably indicates neurosis rather than pleasure. Why do we take such snapshots? And what are we going to do with them?

Through photography, we express our complementary desires for intimacy and exteriorization. We have a desire to show ourselves and a desire for intimacy. It gives us the feeling that we exist, from the first months of life when children discover themselves in their mothers’ faces. The psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott proposes that the presentation of the self in everyday life is a permanent way of looking through the eyes of others, and, in a broad sense, at the reactions of others. It is the confirmation of the self. The word “extimacy,” proposed by the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, sums up this dynamic: it is the process by which fragments of the intimate self are offered to others to be validated. It is not about exhibitionism. On the contrary, the desire for extimacy is inseparable from the desire to find oneself through the other. We need intimacy to build the foundations of self-esteem: because we know that we can hide, we want to reveal certain privileged parts of ourselves. This process can be linked to the distinction between the public self and the private self.

Industrial societies have transformed us into image-addicted citizens. The desire for extimacy induces us to share our images with a crowd. Ultimately, having an experience becomes the same as taking a photograph of it, and participating in a public event is increasingly equivalent to looking at it in photographed form. Paraphrasing the French poet Stéphane Mallarmé, who used to say that everything in the world exists to end up in a book, Susan Sontag ventures to propose that “today everything exists to end in a photograph.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.