Maximilian I, the Austrian archduke who regretted trying to conquer Mexico

British historian Edward Shawcross presents a very readable biography of a royal caught up in an ill-fated imperial adventure

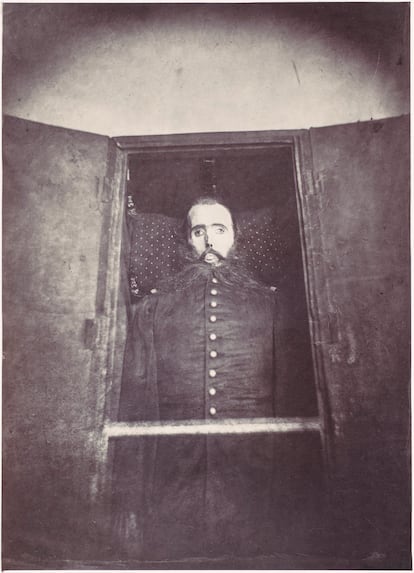

One of the most tragic and absurd adventures in history belongs to Maximilian I (1832-1867), the Austrian archduke and brother-in-law of Elisabeth (nicknamed Sisi), the Empress of Austria and Queen of Hungary. The extravagantly bearded royal unexpectedly found himself enthroned as the Emperor of Mexico and met his demise before a firing squad of his former subjects. Maximilian’s life was full of surprises, and so was his death, as can be seen in the astonished look on his embalmed face (there’s a photo). Maximilian and his Belgian wife, Empress Charlotte (sister of Leopold II), aimed to transplant the customs and etiquette of the Habsburg court to the vastly different landscape and people of Mexico. The tragicomedy of his failed endeavor can be summed up in one tombstone-worthy phrase: “I shouldn’t have come here.” A revealing and very readable biography of the archduke — The Last Emperor of Mexico — follows an existential and political misadventure that has always fascinated British historian Edward Shawcross, who calls it “a storyteller’s delight.”

Fernando Maximiliano José María de Habsburgo-Lorena (Maxi to his family) made lots of powerful enemies during his ill-fated attempt at conquering Mexico: Mexican President Benito Juárez, U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant (who remembered Maximilian’s support for the Confederate Army) and even Karl Marx, who regarded Maxi’s Mexican empire as one of the most monstrous episodes in the annals of history. Despite being the younger brother of Franz Josef I, Emperor of Austria, Maximilian sought Napoleon III’s help in his decidedly quixotic attempt to establish a monarchy in Mexico. But the European blue blood raised in luxurious palaces met his demise with his back to a humble adobe wall as a Mexican firing squad on a hill in Querétaro aimed and fired at point-blank range.

Shawcross tells Maximilian’s story within the geopolitical backdrop of European imperial adventurism confronted by young, American republics. In 1863, the new emperor arrived in Mexico, backed by Napoleon III’s army. The French cited Mexico’s failure to pay its debt obligations as justification for their intervention. Maximilian was chosen to lead the invasion, perhaps because he was the only man available. Some suggested he was pushed into it by his mother, Princess Sofia of Bavaria, who had a close relationship with the Duke of Reichstadt, the hapless son of Napoleon Bonaparte and Maria Luisa of Austria.

Shawcross acknowledges Maximilian’s Mexican expedition as a significant historical event, if somewhat comical. “It’s a story that would be deemed too implausible for publishing as a novel,” said Shawcross. “Anecdotes such as Maximilian, a nature lover, being captivated by butterflies during a battle, or Charlotte losing her temper with the Pope, are truly remarkable.” His book shows Maximilian’s story was a tragedy foretold. Why didn’t they realize it? “Hubris, pride. The story of Maximilian and Charlotte is a classic tale of failure due to arrogance and delusions of grandeur. After serving as commander of the Austrian Navy and viceroy of Lombardy-Veneto, Maximilian was leading a rather uneventful existence at his fairytale Miramare Castle in Trieste (Italy). Naturally, he jumped at the chance to become emperor of Mexico. France and Austria had recently clashed over Italy, and Franz Josef I saw Mexico as something that would get his younger brother Maximilian out of the way and maybe even yield some financial reward. He enlisted Napoleon III’s support who, after selling Mexico as a land of abundant resources and opportunity, eventually abandoned Maximilian to his fate.” Creating a new monarchy wasn’t an entirely absurd idea at that time, says Shawcross. Monarchies had been reestablished in Greece, Sweden and Belgium, and the prospects seemed promising. But Mexico was a very different place.

Shawcross admits to feeling some sympathy for Maximilian and Charlotte, despite the pain and damage they inflicted on Mexico. “The two were sent off to establish a monarchy and restore order in a chaotic country, but were later abandoned. Their intentions may have been good, but the brutal French invasion to oust the democratically elected government in Mexico had a terrible impact. Maximilian’s chances of success were slim, as initial support dwindled and promises were broken. Furthermore, Maximilian never distanced himself from the invading army and failed to win over the Mexican people when Napoleon III prematurely declared victory and withdrew his troops.”

The history of the French invasion (with help from Great Britain and Spain) and the establishment of Maximilian’s empire is marked by significant events like the Battle of Camarón, the heroic resistance of 65 French Foreign Legion soldiers against 2,000 Mexican soldiers. Juan Prim, a Spanish general and statesman who was briefly Prime Minister of Spain, led the Spanish forces in Mexico. Prim opposed Napoleon III and Maximilian I, leading some to speculate that he harbored his own ambitions of becoming emperor. “The story is wide-ranging and filled with many subplots and fringe characters that make it difficult to explore in its entirety,” said Shawcross. One of those fringe characters was Maximilian’s younger brother, Ludwig Viktor, a cross-dressing homosexual who dreamed of becoming king of Brazil. Then there is Félix Salm-Salm, a Prussian military officer of princely birth and a soldier of fortune who supported Maximilian. His wife, Agnes, who was born in a circus, reportedly offered herself nude to one of the Mexican colonels who were guarding Maximilian, in an attempt to secure his release from prison.

One of the author’s favorite anecdotes was when Maximilian and Charlotte arrived in Veracruz and first laid eyes on their kingdom. Maximilian put on traditional charro attire for the occasion. “They arrive with great fanfare, only to find empty, dusty streets. Buzzards are soaring overhead. While their reception in Mexico City was grand, this initial experience felt like an ominous premonition.”

Shawcross is struck by Maximilian’s firing-squad execution, which was a rare occurrence in those days. Napoleon I and Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederate States, were not executed, although Agustín de Iturbide, the first Emperor of Mexico, also faced a firing squad. Before his execution, Charlotte had traveled to Europe to seek assistance from Napoleon III for her husband and his crumbling empire. She struggled with mental health issues for the rest of her life, though she would lament the loss of her husband in brief moments of lucidity. The couple did not have any children, although Maximilian reportedly had an Indigenous lover in Cuernavaca.

What about Maximilian’s strange, forked beard? “This style was more prevalent in the past and seen as quite elegant. I think it gives him a hipster air. In fact, he even refused to trim it to disguise himself during a prison escape attempt. Napoleon III was also well-known for his mustache, which he meticulously styled with wax.” Édouard Manet’s painting of Maximilian’s execution depicts him quite normally, but the photograph of his embalmed body is very striking. “Manet’s painting contains inaccuracies. Maximilian was positioned on the right, not in the center, from the perspective of the firing squad. Also, he wasn’t wearing a hat. Still, the painting successfully conveys a sense of stoic resignation. His body was poorly embalmed by obviously disrespectful doctors. The decomposing body remained in Mexico for six months before it was shipped back to his home country.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.