A sexual, social and political history of the mustache: “Joaquin Phoenix couldn’t have had a beard in ‘Her’: it had to be a mustache”

The tash is enjoying a renaissance among pop stars, movie actors and the wider public after decades of being irretrievably associated with military despots or the gay culture of the 1970s and 1980s

In a scene from Spanish director Pedro Almodóvar’s 1993 movie Kika, Verónica Forqué encourages her home-help, Rossy de Palma, to shave her top lip, on the basis it will make her more feminine and attractive. Rossy replies: “Mustaches are not the exclusive patrimony of men. In fact, men with mustaches are either gay or fugitives, or both at the same time.” Even in the context of gross comedy, the observation is not entirely without basis. The history of the mustache, at least in Spain, was embedded in that myth for years. On a global scale, mustaches have been associated with war: Greeks and Romans considered a luxurious beard a symbol of manhood, but found that a mustache was better for the battlefield to prevent their enemies from grabbing them in battle. They have also been associated with love: in the 19th century, British men sported a mustache to announce that they were single and of good social standing.

Some marketing theories posit that men with carefully groomed beards and mustaches inspire confidence and help advertisers to sell more products. Others still link a mustache with the darkest side of 20th century militarism and names like Hitler, Franco and Mussolini, who have quite the opposite effect.

In the US, mustaches remain important enough the American Mustache Institute was founded in 1965 and takes its work very seriously. The institute carries out surveys, which do not always work in its best interest: in 2013, one poll revealed that 73% of respondents associated mustaches with alcoholism and only 30% believed a man in a managerial position should wear one. The institute’s president, Aaron Perlut, told The Atlantic in an interview that they had saved the job of a waiter in Georgia who was threatened with being fired if he did not shave and had a student called Sebastian Pham reinstated at his high school in 2006 after he had been expelled for refusing to remove his mustache. Facial hair is politics. In fact, a mustache represents a man’s entry into politics. If a five o’clock shadow is the first outward sign of adolescence being left behind, it also represents a rite of passage toward becoming a voter and taxpayer.

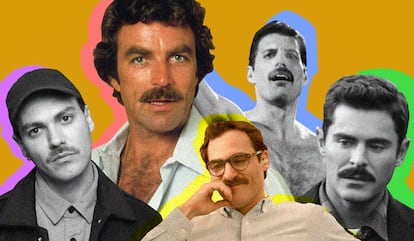

Today, the American Mustache Institute only exists on Twitter and Instagram, and it does not have a vast following: the mustache is no longer conflictive. Justin Bieber has one, and Zak Efron sports one for his latest movie, The Greatest Beer Run Ever. The pandemic lockdowns did a lot to normalize mustache relations: an opportunity to experiment led many people to realize the look suited them and they retained it when the streets reopened. In any case, the mustache renaissance has been underway for years.

The mustache of the future

Sergio Lopez, a Goya-nominated make-up artist, believes the current trend for top lip adornment is “an inheritance of the hipsters, a natural evolution of that bushy beard [which ruled supreme in the 2000s until it became almost a parody in the 2010s].” Spike Jonze, a totem of hipsterism, gave Joaquin Phoenix a mustache in his 2013 hit movie Her. It was such a groundbreaking move that review website Gizmondo noted: “Her looks so good that you won’t care about Joaquin Phoenix’s mustache.” The review also wondered: “I’m not sure which is the scifi part, though: that a man could fall in love with his computer, or that an intelligent being of any sort would date a dude with that mustache.” James Franco in Milk (2008) and Brad Pitt in Inglourious Basterds (2009) had sported mustaches before that but both were period pieces and the facial hair part of the actors’ characterization. Her was set in the future, and the mustache was simply there.

“That was the turning point for the return of the mustache: a cool dude, well-dressed… and with a ‘tache,” says Blanca Lacasa, a journalist, writer and firm defender of masculine facial hair. “Furthermore, being set in the future, the movie left a prophecy: the modern and interesting man of tomorrow will wear a mustache. It wasn’t random or coincidental. Joaquin Phoenix couldn’t have had a beard in Her: it had to be a mustache.”

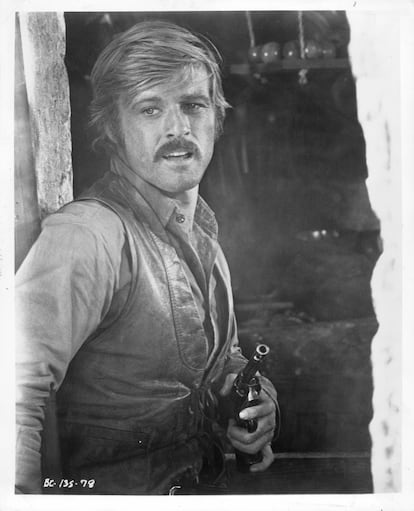

Lacasa is a keen classifier of the mustache. “I didn’t like those of the 1930s and 1940s very much, like Errol Flynn and Clark Gable [pencil thin and very profiled efforts]. The best mustache is the 1970s mustache. Full, bushy, not scruffy, but also not perfect. My love for them began with Robert Redford in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969). I also liked Elliot Gould, Tom Selleck and Burt Reynolds, who had fantastic mustaches. But my favorite is Sam Elliot’s, a mustache so sexy you want to bite it off.”

Alberto Mira, a student of cinema and a professor at Oxford Brookes University, is not a huge fan of the mustache himself, but he makes a compelling point about the sociopolitical connotations where they are involved. “It’s interesting that it was only in Spanish cinema that a mustache implied fascism. Elsewhere, such as in Hollywood, it implied respectability.” Lacasa agrees: “In Spain we associate it with Franco, with [former Prime Minister José María] Aznar, of right-wing men, with a certain military order. But overseas this wasn’t the case. Think about France, of Jean Rochefort, who had a very cool ‘tache, or Dennis Hopper in the US, a symbol of libertarianism. That scruffy mustache was not only sexy, it was left-wing.”

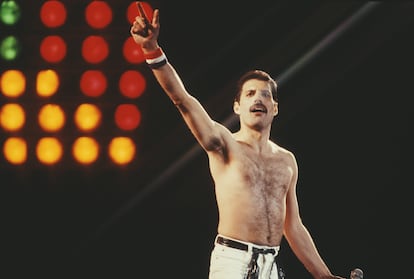

Mira also highlights the sociosexual connotations of mustaches: “We cannot ignore the mustache’s association with gay men, which is an evolution of the dapper mustache of the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century and which in turn leads to the brimming mustache of the 1970s,” an exaggeration of the hyper-masculine esthetic that reigned during that decade and that gay men ended up appropriating. “I think from that moment, when the mustache became associated with gay men, heterosexual men started to avoid it,” Mira concludes.

There is of course a gay icon of the 1970s and 1980s who wore a mustache and converted it into a symbol: Queen front man Freddie Mercury, who wore his as a symbol of sexual freedom. During that era, it could be said that the mustache was both an image of American masculinity (actors like the aforementioned Reynolds and Selleck, whose heterosexuality was so overt and overwhelming that a simple mustache could not call it into question) and of European ambiguity.

Clean-shaven for MTV

“At a cultural level, the mustache has always been used to masculinize men,” says López, “and in some cases it has been used as an association with a profile of power. In fiction, it also marks an era: depending on the period and the type of mustache in question, it can pinpoint a character from the 1920s to the 1970s.” This all changed in the 1990s. “Then, a cleaner, more natural esthetic was being sought.” For evidence we need look no further than Calvin Klein advertisements, MTV and the popularity of teem shows that invaded prime time and turned facial hair into a throwback. Beards became the symbol of men who didn’t pay attention to their appearance (Homer Simpson and his ever-present five o’clock shadow) or to differentiate between a clean-cut matinee idol and a darker characterization, as when Brad Pitt sported one in Seven and Legends of the Fall to portray a tough guy type overwhelmed by tragedy.

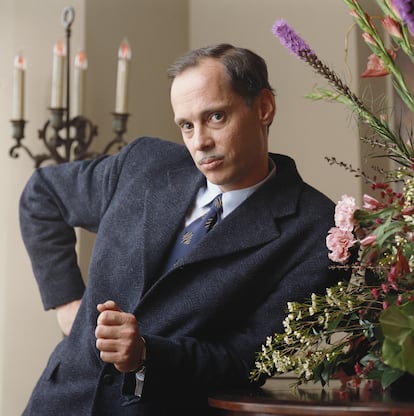

In the 1990s, a mustache was the exclusive preserve of the extravagant homosexual (John Waters), the comedian (Eddie Murphy) or the androgynous superstar (Prince). The fact that a mustache was not for everybody was framed in a famous episode of Friends, when Chandler decided to grow one to look more like Monica’s boyfriend, who was played by Tom Selleck. The results inspired the mirth of the rest of the group: during that time, only Selleck could keep his mustache and his dignity.

But a review of the history of the mustache would not be complete if it did not end at the face where it is most combative and militant: that of women. Where previously we spoke of the emergence of a mustache as a point of pride for young men on the path to maturity, in women it is seen as the first sign of a body rebelling against the supposed norm. “Few women in the public eye have had the courage to retain their upper lip hair. So few that the two who did, Frida Kahlo and Pattie Smith, are constantly remembered because of it,” wrote Raquel Peláez in an article for S Moda.

In the 2000s, with the mustache still banished from the ideal of masculine beauty, it is striking to remember that the most famous mustache in pop was sported by a woman: JD Samson, of US electroclash band Le Tigre. “”Something I recommend to everyone is to try to turn that thing that makes them feel most uncomfortable about themselves into a celebration,” Samson said in a video in which she explained her decision not to wax her upper lip. “Ever since I did it, it has changed my life.” Let’s follow her advice. Let’s free the mustache.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.