Indiana Jones in search of the lost adventure

The last installment of the saga starring Harrison Ford also marks the end of a way of viewing a genre that has fascinated entire generations

In the foreword Frederic Prokosch published in the early 1980s for the reissue of his travel classic The Asiatics (1935), the Wisconsin poet and novelist wrote: “What was it that I found so enthralling in that dream of an impenetrable Asia? Undoubtedly, their inscrutable being, like that of snakes and insects; that reign of gigantic mystery that forced my imagination to fight tooth and nail with the Asian notions of transience and evanescence, of sanctity and perfidy, of horror and eternity.” Like Don Quixote and the books of chivalry, young Prokosch found his cause in the hundreds of volumes he read at the Linonian Library in New Haven. He was a young man “and inexperienced”, but with the intuition “of an animal,” and according to the legend, he embarked on the greatest of adventures: traveling the map of the imagination, without even leaving his desk.

It is not easy to mark out the how far-reaching the impulse of adventure is in the history of cinematography, which Juan Eduardo Cirlot defined in his famous Dictionary of Symbols as “the search for the meaning of life: danger, combat, love, abandonment, encounter, help, loss, conquest, death.” The struggle against evil, Cirlot said, “is the ethical aspect of the adventure, as the search for the beloved is the erotic-spiritual aspect.” The passion for travel and fiction, for exploring other worlds and, above all, for narrating them, has existed since one of the pioneers of cinema, George Méliès, director of a small Parisian theater of magic and illusions, knew how to sense the public’s desire to fly to the North Pole or the Moon. Adventure films have room for every imaginary world: jungles, seas, forests, deserts, and whole galaxies; pirates and treasures; Sinbad the sailor and Robin Hood; prehistoric animals, shipwrecks and voyages a thousand leagues of under the sea. The action, historical and fantasy genres seek the epic of adventure. The western epic, too.

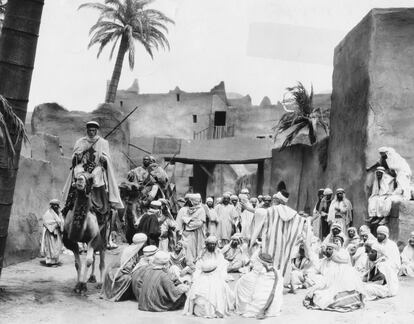

When Indiana Jones landed in 1981, a character who has returned to theaters to bid us farewell in The Dial of Destiny, the splendor of classic cinema already belonged to the past. Most of the teenage viewers of the time had grown up with the heroes inherited from their parents and, although they would have arrived at the movie theaters just in time to see the last double bills of Tarzan and the Marx Brothers, they had to discover a lot of the great adventure cinema on television, in video stores, or in the neighborhood cinemas fighting a losing battle against the changing times. Watching the Viking funeral of Beau Geste, the 1939 classic film by William A. Wellman (the director who left such an imprint on the Spanish post-war generation) was not as exciting on a home television screen as is the oasis of a movie theater during the cultural wasteland of Franco’s regime. Even so, the passion for the adventures of the classics was infectious thanks to films such as Beau Geste itself or Moonfleet (1955), The Tiger of Eschnapur, and its sequel, The Indian Tomb (1959), all three by Fritz Lang; Treasure Island (1934) and Captains Courageous (1937), both by Victor Fleming; King Kong (1933) by Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack; The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932), by Charles Brabin; Gunga Din (1939), by George Stevens; The Thief of Baghdad (1924), The World in His Hands (1952) and Objective Burma (1945), all by Raoul Walsh; Only Angels Have Wings (1939) and Hatari!(1962), by Howard Hawks; A High Wind in Jamaica (1965), by Alexander Mackendrick, or, in one of the few female examples of an eminently male tradition, Anne of the Indies (1951), a jewel in the treasure trove of Jacques Tourneur’s filmography.

Every epic requires a hero and that implies more than just a good actor. In 1979, when Steven Spielberg and George Lucas signed an agreement with Paramount Pictures to develop a series of films (five to be precise) inspired by pulp novels and Hollywood classics, the main stumbling block was finding a new archetype and a performer able to embody him. The challenge was to find an actor with charisma and good looks who was able to charm audiences like the old Hollywood matinée stars. When Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark was released in 1981, I was 13 years old. There is an anecdote that sums up the impact on millions of teenagers around the world on discovering a popular icon of their own. In my case, like the psychopath Jack Torrance in The Shining, I spent a sleepless night filling every page of my diary with a single three-word sentence. My mantra, very much of the time as well, was I love Indy.

A revelation that owes almost everything to Harrison Ford, the actor who knew how to flesh out the character of a hero made from the scraps of an anti-hero. The original idea was to mix the classic film noir figure of the lone detective embodied by Humphrey Bogart, with his ability to move in any underworld with insolence, insight and a Fedora hat, with the athletic and chiseled body of James Bond. His trademark hat and whip are in line with the idea of Chaplin’s bowler hat and cane, but never losing sight of Tarzan’s acrobatic targets. The original candidate to play the character was Tom Selleck, who portrayed a more virile and mischievous Indiana than Ford, more along the lines of 007, but who responded less well to the yearnings of the generation that burst onto the scene in the eighties.

Ford was handsome without knowing it, or caring to know it, a sly skeptic on the surface but with the nobility of a sentimentalist at heart. His Indiana had a serious and introspective side. A learned and erudite man whose adventurous individualism was sustained by his sense of professional duty and his principles as an archaeologist. He was a treasure hunter, but without personal greed or interest in fame. He believed in the idea of the common good of museums. A man, in short, of a very sexy solidity. If we grant that one of the best sequences in Steven Spielberg’s filmography is the final conversation on the boat in Jaws between Robert Shaw, Richard Dreyfuss and Roy Scheider, perhaps we find Ford in the blend of these three men. He is an actor capable of being credible as the passionate academic (Dreyfuss), as the furious and lonely adventurer (Shaw), and as a man of order (Scheider) able to fight relentlessly against evil, be it sharks or Nazism.

Indiana Jones was a hero for all audiences, but his costume was tailor-made for the generation of the schoolyard stigma in the face of early divorce, those who missed the explosion of freedom in the seventies and gloomily chased their own party. Observers and safeguards of wars and utopias they did not experience and who now witness, perplexed, the dehumanized digital procession of toy villains and superheroes. Neither one nor the other is entirely his world and, in that meager place of their own, the avatars of Indiana Jones portrayed their own life’s ups and downs. The transition from the first feature film to the second, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984), is, to be understood, the same that separates the ghost train at the old amusement park in Madrid from Disneyland’s Space Mountain. The first is an ode to the papier-mâché of classic cinema and the second embraces action as the playful adrenaline of a roller coaster.

However, the most complete of the saga, the one that has contributed the most to the construction of the character from that generational perspective, is still Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. It is also, to date, the highest grossing in the series. Released in 1989, the third film, scripted by Jeffrey Boam, travels back to Jones’ origins through a prologue in which River Phoenix (another generational myth who had played Harrison Ford’s son in The Mosquito Coast) brought him to life as a teenager. In another genius twist, his father is played by Sean Connery: literally, James Bond’s blood ran through Indy’s veins. The whole film is a father-son settling of scores in which the feeling of orphanhood of Junior, as his father calls him, prevails. It is something that connects directly with the heart of Spielberg’s cinema, one of the filmmakers who has best portrayed the melancholy of childhood and youth in the face of family dysfunction. At one point in the film, Connery reproaches his son’s laments with brutal honesty: “I was a great father. Did I ever ask you to brush your teeth? Did I ask you to do your homework? I respected your privacy and taught you to be independent.” To which Indy replies, “The only thing you taught me is that you cared more about people who died 500 years ago.” The child’s loneliness was sealed.

The other great pillar of the saga is its contribution to romantic comedy. That is, the role of the hero’s love life. The character of Marion and the choice of an actress with the personality of Karen Allen is reminiscent of the impertinent and independent heroines of Howard Hawks’ comedies, from Ball of fire to Bringing up baby. Marion was also at the center of one of the most decisive sequences of the saga: her kisses on Indiana’s wounds, which revealed, with that perfect blend of sensuality and humor, the secret power of the character is his scars.

The hero’s farewell in The Dial of Destiny closes the circle that began more than 40 years ago in a lost place in the Amazon. Everything has changed since then, including a way of making and understanding popular adventure films. Time is this time the lost treasure and, at 80 years old, Harrison Ford, in James Mangold’s proven professional hands, James Mangold, dares to face the truth about life, with its unfathomable end. Character and actor are today a legend and, therefore, the decision to close years of travels, adventures and mysteries with the dignity of an old man is exciting. It is that quality of flesh and blood that distinguishes Indy from the new fluid society to honor him eternally in the Olympus of the old adventurers. Those who, like Prokosch surrounded only by maps and books, were able to illuminate the world from a desk. Or from a movie theater.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.