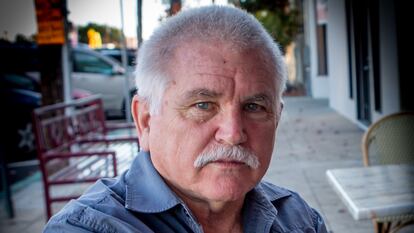

Mike Davis, the author who exposed LA’s dark underbelly, dies at 76

His book ‘City of Quartz’ became a bestseller when it was published, despite its pessimistic portrait of the Californian metropolis

Many writers have tried to unravel the vast, unfathomable, and at times impenetrable city that is Los Angeles. Upton Sinclair tried in the 1920a, when he moved to California from New York. The veteran writer John McPhee has documented every inch of the West Coast, while Joan Didion and Kevin Starr also attempted to explain the city. But among these works, there is one that stands out, City of Quartz (1990) by Mike Davis, who Tuesday, at the age of 76 from esophageal cancer.

Davis was born in Fontana, about 60 miles east of Los Angeles. During his childhood, he saw how the lemon trees in his town withered due to the pollution produced by a nearby steel mill. His mother had Irish roots and his father Welsh origins. Both left the East during the Great Depression to head for the promising West. His father was a butcher, a faithful believer in the unions, but at the end of his life, he saw the US labor movement crushed by industrial power and his pension was taken from him. Davis told the Los Angeles Times in 2004 that it was very hard to see his parents lose their beliefs.

Pessimism marked the work of the Marxist academic, who saw Los Angeles as both a utopia and a dystopia of advanced capitalism. That pessimism cast a long shadow over his writing, with his body of work showing at-times prophetic insight. In 2005, after the bird flu, he wrote The Monster at Our Door, an essay that warned of the danger of a catastrophic pandemic for humans. “We are going to see discontent on a national level that is going to reach the streets,” the author told this newspaper in the midst of the coronavirus crisis, when his essay was reissued.

In 2020, Davis co-published Set the Night on Fire with historian Jon Wiener, an 800-page volume on anti-racist social movements in Los Angeles in the 1960s, and how they fought the white corporate minority that controlled the police.

His most famous work, City of Quartz, is a 400+ page chronicle, built on Marxist theories from Gramsci and Marcuse, that explains the disparities and injustices in Los Angeles’ urban systems and neighborhoods. The villains are corrupt mayors, racist police chiefs and developers such as Harrison Otis and his son-in-law, Harry Chandler, who bought more than 45,000 acres of land throughout the city in the late 19th century (land that would later multiply in value with the completion of the Los Angeles Aqueduct), while manipulating a corrupt business class with their newspaper, the Los Angeles Times. The book also explains how neighborhood organizations, such as NIMBY (Not in My Backyard), offered a counterweight to the rampant development.

City of Quartz became a bestseller when it was released. It was described at the time as a work of excessive pessimism. Indeed, when it was first published, some East Coast critics accused Davis of a certain parochialism. “Sometimes he writes as if Los Angeles, sheltered by sea, mountains, and desert, existed on its own,” wrote Bryce Nelson in The New York Times, in 1991. But there is no doubt today about its scope and vision. The oppressive dynamics Davis outlined in his book were particularly evident in 1992, when riots broke out following the police beating of Rodney King. And over the decades, it has become a noir hit of sociology – to the surprise of Davis. “I was utterly shocked that anybody bothered to read this book,” he said in a 2020 podcast.

Davis, who won of the famous The MacArthur Fellows Program in 1998, was always a provocative thinker. The same year he was awarded the so-called “Genius Grant,” he published Ecology of Fear, which includes the essay The Case for Letting Malibu Burn – a fierce critique on how local housing policies and corrupt developers allowed an area vulnerable to forest fires to be developed.

As a teenager, Davis read Gandhi and the beatnik poets. He was 16 when he was invited for the first time to a San Diego rally for civil rights. Seeing so many people willing to fight against the system was a turning point for Davis. After that, he joined the political organization, Students for a Democratic Society. Davis had to drop out of school when his father, who was a butcher and a truck driver, fell ill. The butchers’ union gave Davis a scholarship to study economics and history at the University of California in Los Angeles. Upon graduation, he edited left-wing publications and taught Urban Theory at the Southern California Institute of Architecture, where he remained part of the faculty for decades.

Since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, Davis has been confined to his home in San Diego, where he lived with his wife, Alessandra Moctezuma (daughter of cult Mexican film director, Juan López Moctezuma) and their two children. He also had two other children, born from one of his five previous marriages. “I have had two cancers,” he told EL PAÍS in 2020. “My immune system is practically destroyed. Basically, I consider this a death sentence,” he said. This summer, his wife posted on Facebook that Davis was no longer receiving cancer treatments and had moved to palliative care. In July, during one of his last interviews, he told the Los Angeles Times that he was sorry he was not going to die in the trenches, fighting for social justice.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.