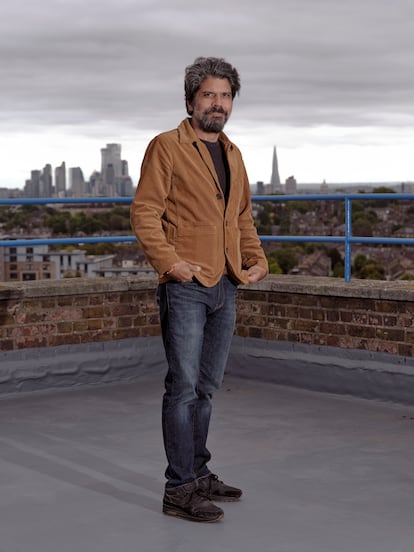

Essayist Pankaj Mishra: ‘The United Kingdom is Europe’s most ideologically self-delusional country’

The Indian-born writer is one of the most provocative and perceptive intellectuals of our time. Based in London, he challenges the West’s narratives of liberal consensus. Now, he returns to the novel to reflect on uprootedness

Writer Pankaj Mishra, 53, always wanted to be a novelist. However, since he published his acclaimed novel The Romantics 22 years ago, the provocative and perceptive intellectual has primarily written criticism and essays that express his clear vision of international reality. His writing highlights the contradictions and miseries of both his native India and the West, where he now lives. In his book Age of Anger: A History of the Present, Mishra strove to understand and explain contemporary society’s generational rage, the wave of populism, xenophobia and racism that has served as a perfect springboard for demagogues and opportunists. The tome established the author’s status as one of the 21st century’s most provocative and stimulating intellectuals. He does not shy away from controversy. Take, for example, his dispute with historian Niall Ferguson, whom Mishra accused of conveniently ignoring historical facts that didn’t fit Ferguson’s narrative of a West-dominated past. The British author alleged that Mishra had called him a racist and demanded a public apology; Mishra never apologized. He also wrote an essay – Jordan Peterson & the Fascist Mystique – about Canadian clinical psychologist Jordan B. Peterson, who is famous for his attacks on gender identity and defense of the traditional social order. An angry Peterson responded by calling Mishra an “arrogant, racist son of a bitch” on Twitter.

The interview below took place in the writer’s light-drenched, book-filled office in London’s Islington neighborhood. The author spoke to EL PAÍS about the state of the world today and his new novel, Run and Hide, which narrates the lives of three men who leave poverty behind to attend the prestigious Indian Institute of Technology and must pay the price of rootlessness for their success.

Question. The metaphor of rootlessness has gained momentum in India and China.

Answer. That has been the case since the beginning of the 19th century. I think rootlessness is the fundamental human experience of the last 200 years. In China or India, the transition from the countryside to the city has accelerated. Nineteenth century literature discusses this transition a great deal: how people leave their family and community to become individuals in the big city and become confused and disoriented. Back then, that process happened over the course of decades, but in India and China it has happened in a span of only 20 or 30 years.

Q. The really disheartening thing is that there is no turning back.

A. You move away from your roots, and you become uprooted forever. There are no places left in the world where you can drop an anchor. That’s what has happened to a lot of these people, hundreds of millions of them no longer have a place to return to, even if they wanted to. The places where they grew up or were raised have been radically transformed. By embracing this project of individualization, modernization and prosperity, they have condemned themselves to eternal rootlessness.

We see how the social contract of solidarity and compassion has been delegitimized and many feel hopeless

Q. Is that nostalgia for a past that no longer exists or a criticism of false hope?

A. We have long believed in this ideology of individual growth, of individual improvement. It was embraced by people who come from societies like India, which had always emphasized some kind of collective welfare, which it had valued above everything else. These were not societies that cultivated individualism, a bleak vision of human life that disdains the role of society, collective action, the role of solidarity or empathy, of compassion. Today, we see how that social contract has been blown up, has been delegitimized. And many people feel hopeless. They’ve aspired to that individualism, they’ve reached that society where, in theory, merit was rewarded, only to discover that it was used against them and has structural imbalances and injustices that end up determining their fate.

Q. And in the end they seek extreme or populist solutions to address that system’s problems.

A. People will always be attracted to far-right groups, such as Spain’s right-wing Vox, because they feel that the traditional parties no longer represent them. They have become technocrats and are far removed from ordinary people...I find [Spanish] deputy prime minister Yolanda Díaz’s campaign to go out into the streets and listen to be very interesting. How could no one have thought of that before? That a relevant political figure has to do that gives us an idea of how disconnected the left has been from the people in the daily process of governance. That gap needs to be closed, or it will end up being filled by groups like Vox or Meloni [Giorgia Meloni, the leader of the Brothers of Italy].

Q. The brief mandate of Liz Truss has managed to increase the sense of chaos in the United Kingdom. The Conservative Party is in free fall and the country is seen as the laughingstock of the international community.

A. Such a disaster never should have happened in a country that has so much wealth and talent. I believe that the post-Brexit fate of the United Kingdom under Johnson and Truss should be a warning for all traditional right-wing politicians in Europe, who have either allied with far-right demagogues or amplify their rhetoric…It’s become clear that culture wars are shattering social cohesion, and that arrogant fantasies about imperial-era power are hindering the ability to make the right political and economic decisions in today’s complex world.

The fate of the post-Brexit United Kingdom, under Johnson and Truss, should be a warning for traditional right-wing politicians in Europe

Q. You have been very critical of the country you live in, the United Kingdom, and how it deals with its colonialist past.

A. The United Kingdom is the most ideologically self-delusional country in Europe. Practically every country on the continent has reckoned with its past. The most extreme case would be Germany, with the serious moral lesson learned: never again. Italy may not be so clear about Mussolini or what he represented, but there’s still a stigma attached to fascism. In Spain, too, many people are wary of the Francoist past. But in the United Kingdom imperialism is still seen as a benign force. Meanwhile, the rest of the world – much of which lived under [British colonial] rule – rejects that perception entirely. That’s why the British keep indulging themselves in these pathetic fantasies of Brexit or Global Britain [Boris Johnson’s international policy]. They have told themselves that they are self-sufficient and that they don’t need the EU, that they can go back to forging alliances with countries like India and the rest of the Commonwealth.

Q. But that debate is occurring, even if it is marginal.

A. Minorities living in the United Kingdom have started the conversation, and it’s met with stiff resistance. Here, the media is mostly very right-wing. They have no time for debate. They describe such criticisms as woke [the progressive culture that champions causes like environmentalism, feminism, trans rights advocacy, and anti-racism].

Q. People think of you as having a “global south” perspective, which sees the West from a different angle. What do you think of the intense cultural wars raging in the United States and the United Kingdom?

A. Many social issues, such as inequality and historical injustices, were removed from public debate a long time ago. Many on the left turned to the socially liberal issues with which they thought they could win easy victories. And in the last 20-30 years there has been a mini-revolution that has brought about huge advances in issues such as gender equality and gay and trans rights. As a consequence, a sector of the population, as well as part of the left, decries the amount of time spent on those battles at the expense of economic inequalities, or more pressing issues that have to do with getting food on the table. [The mainstream left is] delighted with globalization, so they’re focused on identity issues. And now that it has become clear that globalization has not worked well for many people, the extreme right is the one to reproach them for having devoted themselves to protecting sexual and racial minorities while the rest of the population suffered.

Q. You have also objected to the West’s unwavering anti-Russia, pro-Ukraine alliance.

A. In that part of the world [the Global South], we are always going to have a different opinion because we come from a different historical experience. If you grew up in India, you’ve been exposed to a narrative in which imperialism was an ever-present identity. During the Cold War, it was not the “free world” countries that helped us; it was the Soviet Union. [The same was true] if you lived or grew up in South Africa. Of course, we condemn the aggression against Ukraine. We find it a cruel and evil thing to do. But we are not convinced by the narrative of a worldwide alliance of democracy against authoritarianism. Everything is more complex and requires nuance. All those countries are appalled by what Putin has done, but they wonder what the point of sanctions is. Many of them are not going to endorse those measures. Why is there a need to punish the Russian people? Why this Russophobia? If sanctions did not work on small countries like Cuba and North Korea, why would they work on a superpower like Russia? Surely it will end up selling its oil to other countries to finance the war. One is forced to condemn [the West’s] moralizing criticism when all our energy should be devoted to ending the war as soon as possible.

Q. So, should we sit back and let all these authoritarian leaders who control more than half the world do whatever they want?

A. Of course not, but how do we fight them? Can we really stand up to a nuclear power on the battlefield? What kind of risks are we taking? At the time, many of us warned of a nuclear threat scenario, and now everyone is talking about it. No one is a bigger critic of [Indian Prime Minister] Narendra Modi than I am. I have been opposing him for 20 years. Would it occur to me to suggest the idea of fighting him on the battlefield? Do we have to confront him through sanctions? No, absolutely not. In the fight against Modi, Indians must take the lead, not foreigners. That’s why I don’t understand all this Cold War rhetoric, this rhetoric of democracy versus authoritarianism, of the free world versus the unfree world. We should abandon these tired notions, which are not helpful at all in a world as complex as the one we live in.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.