Mario Vargas Llosa and the Latin American ‘boom’: The extinction of the literary barbarians

The movement to which the Nobel laureate belonged promoted the hyperbolic freedom of a fiction that was unlimited and furiously aware of its own ability to change the world with words and with the courage of inventiveness

We have never known as well as we do now what towering figures two dozen writers from multiple Latin American countries were, more than half a century ago now. There was barely any similarity between them, even though they were all heirs and intellectual offspring of a handful of earlier names with not particularly fertile ties to Spain (with the exception perhaps of three poets, Rubén Darío, Pablo Neruda and César Vallejo, and a precocious short story writer, Jorge Luis Borges, who had few Spanish memories, none of them particularly good). The phenomenon was unusual even for a medium as fond of offering unusual things as the novel: there’s something dreamlike about the informal and capricious inventory of titles that even today remain glued to the hands of readers, unaffected by time, if more so by fashion.

The advantage (or perhaps the disadvantage) for contemporary readers who pick up Conversation in the Cathedral, or The Lost Steps, or Tres Tristes Tigres, or One Hundred Years of Solitude, or The Pursuer, or Pedro Páramo, is that they will have access to a wealth of endless information about authors that Spaniards during the waning Franco era and the hesitant transition to democracy began to read without having any idea about anything, neither where these writers came from nor who they were in their respective countries. Reading the work of a Colombian writer dressed in a mechanic’s jumpsuit ceased to be an extravagance and became instead a pleasurable obligation, just as taking in the lilting Peruvian language of Vargas Llosa became a happy ritual that anyone could intertwine with the nasal voice of Cortázar and his labyrinths of wit and tenderness without fear of losing their sense of purpose amidst the lusty language used by Cabrera Infante.

That thunderous wave of literary talent reached the publishing houses of a country, Spain, suffocated by protocols and deceitful formalities, unfathomable hypocrisies, and pandemic-era fears, all of which were justified: these works swept them all away, cleaning up the troubled intimacy of countless Spaniards who, from then on, better understood where power and imagination truly lay. With them came the hyperbolic freedom of unlimited fiction, furiously aware of its own ability to change the world with words and with the courage of inventiveness: without preaching, without lessons in morality. And they made money, a lot of it, and perhaps that’s why they also changed the rules of the entire literary market at the time, as well as writers’ contractual relationships with publishers (with the necessary and unruly support of Carmen Balcells’ literary agency).

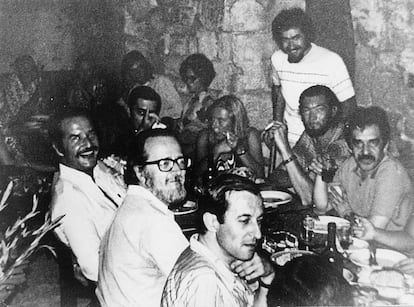

Today they are all ours, truly ours — also Adolfo Bioy Casares, Alfredo Bryce Echenique, Manuel Puig, or Manuel Scorza: it truly is an endless list of towering figures, a vital heritage of a language and its readers, with its turns of phrase, its idioms, its enigmas, and its obsessions. Making the literature of a multitude of Spanish-speaking countries our own is the unprecedented privilege experienced by Spanish indigenism, so jealous of its essentialist identity, so suspicious then of a foreignness that hundreds of thousands of readers denied. And many of them went to Spain, of course: the great political novelist Vargas Llosa was unreservedly intimate in Barcelona with the organized and sensual delirium of García Márquez, while the erotic sentimental humor of the magician Cortázar did not feel out of place there either, nor of course did José Donoso lose value for having lost his seat in the restricted club of a brand, the [Latin American literary] boom, that worked as an advertising catalyst for other writers of lesser stature but nevertheless quite respectable such as Mauricio Wácquez or Severo Sarduy, Copi or Cristina Peri Rossi.

Their unpublished books, their private letters, their manuscripts and their masterpieces live off the privilege of the internet age. The youths who today incredulously discover the stories of Cortázar or the novels of Vargas Llosa, the fabulous diaries and short stories of Julio Ramón Ribeyro, the ruffled nightmares of José Donoso, or the agonizing ruminations of Ernesto Sabato, will be captivated by an addiction with no humanly possible escape. I know them, and I know that the tyranny of great literature works exactly the same with Instagram open on our phones as without it: to trivialize the power of fiction is to begin to lose our sense of reality, because literature is more powerful than Instagram and TikTok combined, even though so many of us have forgotten the furious passion that those books sowed in our heads and the way the narcotic works when our skin is still sensitive and our eyes read “with reading eyes,” as a friend of mine says, because it’s the only way to read, dying of pleasure and without the energy to quell our voracity. It’s happening now, even if we don’t see or hear it: that is the greatest cause of the civil gratitude that Spain owes to a literature it could neither emulate nor avoid. Only the massive mobilization of readers, and not any marketing or propaganda campaign or any other of the often-mentioned nonsense, is the real reason for the invasion of the Latin American “barbarians,” almost instantly transformed into walking icons of an irresistible world.

No melancholy or nostalgia, then, assails us after the passing of one of the greats of a world that no longer exists, because the gift of resurrection is instantaneous and accessible at a click or a subway ride to the bookstore. Today is rather a day for celebrating the exceptional novelistic talent spread across multiple Argentine or Cuban, Colombian or Mexican, Chilean or Nicaraguan accents, with no female writers comparable to the titular barbarians. The worst thing some might think to say today — and that would indeed be a bubbling source of melancholy — is that almost all of them were too manly, ultra-manly, mega-manly without any complexes or apprehension about being so. The reproach will be fair, anachronistic, and conscientiously irrelevant. Or, better yet, ask the incredulous youth captivated by their work.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.