Coldplay: Why such an irritating band can fill more venues than any other on the planet

Chris Martin’s group is the best-selling music outfit in pop today. But many experts despise them. EL PAÍS examines why

Mick Jagger doesn’t hate Coldplay. A few weeks ago, the Rolling Stones singer published a video on his Instagram account showing him in the upper stands of London’s Wembley Stadium, waving his arms to the sound of the Coldplay anthem Fix You. Like the other 80,000 members of the audience, Jagger wore on his wrist a xyloband, the light bracelet that the British quartet has invented for their concerts. The image was startling. “Jagger listening to Fix You at Wembley and keeping the tears at bay,” someone said on Twitter ironically, referring to the tear-jerking effect of listening to the piece. “Mick Jagger doesn’t care if you know he loves Coldplay,” the music medium Loudwire titled a piece of information about the video, noting that it’s a bit embarrassing to declare passion for the music of the British quartet.

Put the words “hate + Coldplay” in Google or YouTube search engines and you will find dozens of articles on the subject. Music critics and aficionados can’t stand them. A few years ago, The New Yorker published an article titled Why I Don’t Like Coldplay and The New York Times critic Jon Pareles, left this phrase for history: “The most insufferable band of the decade.”

But Coldplay is the biggest pop band of the moment. No one can come close to their concert numbers. After a hugely successful UK tour, the band will embark on a world tour in 2023. The 200,000 tickets for the band’s four concert dates in Barcelona sold out in a matter of hours, and in Argentina, Coldplay is expected to perform to over half a million people during the 10 days they will be at River Plate stadium. We are talking about tickets that cost upwards of €105. And yet, Coldplay’s music is hated just as much as it is loved. What have the British quartet done wrong?

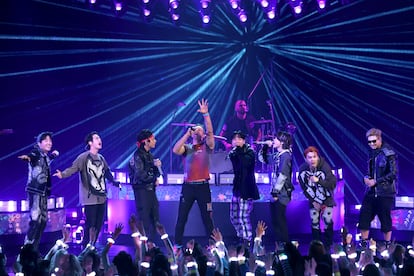

Alexis Petridis, music critic for the British newspaper The Guardian and one of the most influential pop music specialists in Europe, ends his furious analysis of the band’s latest album, Music of the Spheres (2021), with this criticism: “There must be more worthy ways to stay on top.” His theory is that the quartet is obsessed with success and after commercial slips in the past, have decided to play it safe. How? By working the numbers. They selected artists with the most social media followers and platform listeners and went out of their way to have them on the record. Hence, the presence of Selena Gomez and Korean pop stars BTS.

It’s an interesting theory, one that echoes similar criticism from Alfonso Cardenal, the host of the Sofá Sonoro music program on Spain’s Cadena SER radio network. “Coldplay is a band that was aiming for an independent side, so to speak, but the unexpected success of their first album [Parachutes, 2000] turned them into stars, and they decided to stay there by performing commercial pop. Radiohead had the chance to do the same after the huge success of Creep, but preferred experimentation.”

It is worth highlighting what Coldplay critics find annoying about the band’s music: the excess of positivity, songs composed with the aim of being played in stadiums, saccharine melodies, the forced feelgood vibes and the lack of imagination – and this doesn’t just apply to their early songs. And hence the jokes: Coldplay is perfect music for a wedding, indie music for people who don’t like indie… Lanre Bakare is The Guardian’s arts and culture correspondent. When asked by EL PAÍS about why some people have a problem with Coldplay, he says it’s because the band is seen as too commercial. “Those looking for challenging music are put off by Coldplay’s level of success. It is for the same reason that many hate U2, which I think is a group with certain similarities to Coldplay. Also, Coldplay’s tendency to fall into sentimentality is off-putting to some. But the truth is that the mass public wants music that can soundtrack the ups and downs of their lives, and their songs are perfect in that regard,” he says.

Gustavo Iglesias, from Spain’s Radio 3, also defends the band: “Given Coldplay’s massive success, it’s easy to attack them and say that they have sold out or lost their dignity. But if you look at their career, their recent albums haven’t been so bad. Music of the Spheres won’t be an important work in the future of popular music, but I don’t see it as an atrocity either, as much of the critics have said.”

Critics of the band also criticize lead singer Chris Martin for his meekness as a rock star. He doesn’t brag about vices, he grinds at the gym and always has a smile on his face. But this is exactly what Shuarma, the leader of the Spanish group Elefantes, likes about him. “Chris Martin is simple, nothing fancy or eccentric. His power is that naturalness. I think it’s a time when the music culture is closer to the normal person than the rock star,” he tells EL PAÍS. “Music has taken a turn: records are no longer sold and music programs and magazines are no longer so influential. There are no more rock stars, the ones that survive are the ones from yesteryear.”

Shuarma admits he is more interested in Coldplay’s early music than their latest albums. “However, they continue to do wonderfully now as well. They have a tremendous compositional capacity and energy. And collaborating with artists from different styles, as they have done with BTS or Selena Gomez, I think it enriches the music.” Bakare agrees with Shuarma about Martin. “He’s a new kind of pop star, less cool, but who connects on an emotional level and people can relate to. Chris Martin is a nerd who grew up an evangelical Christian. And it has paved the way for musicians with similar profiles, such as Ed Sheeran and Lewis Capaldi.”

It is true that Coldplay has been a stadium band for years, but now it has exceeded expectations. “Nobody can doubt its pull, the figures are tremendous. The images of the Wembley concerts have raised a lot of expectations,” says Cardenal. “Some are not fans of Coldplay, but are drawn to the show. It is also a concert which is considered an ‘event to be at.’ There are a lot of influencers, people taking photos for Instagram. They are fashions that bring together part of the population that wants to involved in what’s being talked about.” And there are the songs, of course, with the rousing choruses that work perfectly for large audiences.

We asked a college student who spent a morning in the virtual queue for Barcelona concert tickets why she wanted to see them. Blanca Liceras, a 23-year-old from Madrid: “I’m not a big fan of the group and I’ve barely listened to their latest album, but I decided to buy a ticket after seeing the videos of other concerts on social media: the lights, the different settings, how much fun people seem to have….”

The members of Coldplay met at university in the 1990s and moved to London full of ambition. “We wanted to meet musicians, the people with whom we were going to conquer the world,” they have reported on occasion. When Britpop (Oasis, Blur, Suede) was beginning its decline, a new generation of British musicians appeared who turned down the volume of the guitars, introduced the piano and spoke of melancholy love. It was the early 2000s. Coldplay, Travis, Keane and Snow Patrol were appearing at the top of the charts.

Of all of them, only Coldplay are capable of reaching large audiences today, partly due to their willingness to be a commercial pop group. Iglesias finds their evolution “quite honest, they have never tried to be an arty or sophisticated group.” Bakare points out: “They are fundamentally a commercial band that sometimes surprises us by winking at Kraftwerk. I always remember Noel Gallagher [Oasis] saying that Coldplay wrote songs for ‘children who wet the bed.’ The truth is that they make songs that connect with people on an emotional level, that’s why they perform in Spain and fill stadiums and Noel doesn’t.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.