Classism, intergenerational conflict, misogynistic lyrics: The hate for reggaeton goes beyond musical taste

Scholars of the genre, and of its closely related trap or urban pop, emphasize that the strong feelings it incites can be due to classism and even age

This will be remembered as the era in which humanity started twerking. Reggaeton has caused a revolution in global music, and it has brought Latin music to the forefront. But the history of reggaeton is also the history of the genre’s persecution. It shares a stigma with other genres that certain sectors of the population —namely older people— don’t seem to understand: from trap or urban pop, with its penchant for autotune, to Rosalía’s eclectic creations, which are a frequent object of controversy on social media. At times, it even seems that declaring one’s distaste for the music of the youth is a sign of distinction. Hating reggaeton has become something to brag about. And its detractors delight in bragging.

From the singer Pablo Milanés to the pianist James Rhodes, many public figures have shown no reservations in declaring themselves against reggaeton and its neighboring genres. As the music grows more ubiquitous and more widely accepted, rejection remains in the air. The genre’s success gives its detractors more opportunities to express their distaste: it is omnipresent on the radio, at bars and in shopping centers.

Reggaeton has been stigmatized since its beginnings. “Even in Puerto Rico, before it was called reggaeton, when it was still called ‘underground,’ it elicited prejudice. Police fined people who listened to it, even inside of their cars and not on a beach or in a public space. They broke their cassette tapes,” says the journalist Pablito Wilson, author of the book Reggaetón, una revolución latina, (or Reggaeton, a Latin revolution) which narrates the genre’s history from its Jamaican, Panamanian and African origins. That cultural cocktail gave rise to the rhythms of dembow, along with many other subgenres of contemporary music.

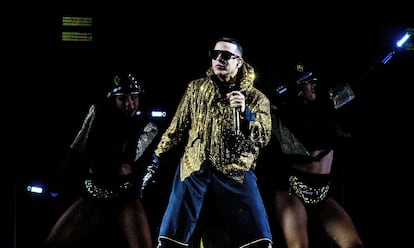

That stigma remained until the genre’s explosion in Puerto Rico, led by artists including Tego Calderón, Don Omar and Daddy Yankee, whose “Gasolina” put the rhythms on the global map in 2004. Since its rough and raw origins, the genre has become more mainstream, directed towards a wider audience. One notorious case is that of Nicky Jam, now a father, who has expressed regret for the lyrics of his early years and now advocates for more responsible content. “Some say that the reggaeton now is rhythm ‘n blues, although there is a phenomenon in clubs that is returning to its origins,” Wilson notes. In 2002, when the style was still in its early phase, a Puerto Rican senator managed to get governmental approval on the island to censor the genre, upset about its violent and sexual content, while supporting more commercial music.

Reasons to hate perreo

Reggaeton’s stigma comes from a combination of several factors. One of them is classism: the contempt of part of the population for the music of the most vulnerable sectors, the working class, migrants. “It is a mixture of classism, misunderstood Europeanism and old colonial prejudices,” writes the journalist Víctor Lenore in the prologue to Wilson’s volume. “We despise three categories of music: music made in Spanish, music made for dancing and music made by artists who come from poor backgrounds,” adds Lenore.

Beyond that, some studies have linked a taste for reggaeton with a low IQ. “Sometimes data is used in perverse ways,” says Wilson. “It has been said that reggaeton followers have a low cultural level, but it is not because they listen to reggaeton. It is because many fans are part of marginalized sectors of society and do not have access to a good education.”

Another factor that contributes to the hatred of reggaeton is its lyrics’ openly sexual content, despite the fact that it is found in many other musical styles: Elvis’s pelvis also caused a scandal in the 1950s. The songs, particularly those of the genre’s early years, are often branded as misogynist. “Some feminist women now defend reggaeton as a way to liberate the body. Others say that it is more of the same, that it does more harm than good,” says Wilson. The Colombian artist Karol G is often pointed out as a feminist reference. Chocolate Remix strives to create queer and transfeminist reggaeton. And Bad Bunny, already a global star, has stood for the feminist, LGBT and anti-racist cause. “We will never overcome the rejection of reggaeton. It’s like racism or homophobia,” he told this newspaper in 2021.

Old men don’t like to twerk

Of course, the generational component plays a role in the rejection of these rhythms. As they age, people tend to close off their musical taste to new currents. They tend to think that the past, particularly the days of their youth, was better than now. On the internet, that contempt is clear in the criticism of Rosalía’s Dadaist lyrics. Those lyrics don’t make sense, some say. Rosalía, you used to be great, former fans write. You’ve lost a fan here, they lament.

“Every so often a new musical style appears with which the new generations identify and which the previous ones reject with similar arguments: ‘that’s not music, just noise,’ ‘the old music was better,’” says Carles Feixa, professor of Social Anthropology at Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona. “If lovers of jazz and swing criticized rock, the later generations rejected heavy metal or punk, the next rejected techno, and all the rest now reject reggaeton and trap,” he summarizes. According to the anthropologist, the clock of musical taste usually stops in youth. Since the appearance of rock n’ roll, new rhythms tend to bring about a generational rupture.

Punk is now in the limelight due to the Pistol series on Disney+, focused on the adventures of the pioneering Sex Pistols, great cultural enemies of the recently deceased Queen Elizabeth II. It sought to be divisive, shocking the bourgeois and creating scandal. Trap music has often been described as the new punk for the new nihilistic generations. With the vehemence of cultural battles on social networks, the debate between the traditional and the modern, between the old rockers and the new trap artists has become more visible. C. Tangana is a rare artist who has managed to build bridges between generations. He won the favor of all audiences by featuring on his El Madrileño album a good part of the Spanish-language music star system that preceded him, such as Kiko Veneno, Jorge Drexler and Andrés Calamaro.

“I don’t think reggaeton is controversial music,” concludes Pablito Wilson. “I think that we are living through times when reggaeton is controversial, but that will pass. In other times, rock, disco music and even tango, which was considered highly obscene, were also controversial.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.