One-year anniversary of Uvalde school massacre marked by frustration: ‘We’re just a number’

The families of the victims want to raise the age to buy semi-automatic rifles, such as the AR-15 used in the shooting, but the measure has been stalled by Republican lawmakers. Meanwhile, teachers say schoolchildren no longer go to the bathroom alone

Hillcrest Cemetery, just outside of Uvalde, is very busy on Mother’s Day. Adalynn Ruiz arrives around noon on Sunday, May 14. She wears a T-shirt that reads “Eva strong,” a phrase that’s become a tribute to her mother, Eva Mireles, a fourth-grade teacher who loved climbing mountains and CrossFit. She was one of 21 victims of the Robb Elementary School massacre, which took place on May 24, 2022, in this southern Texan town. As the hours pass, friends and family join Ruiz in front of her mother’s grave, which is decorated with black and white photographs, balloons and plastic flower crowns. The day turns into something of a party. There are pizzas and a cooler filled with cold beer to stave off the heat. There is even laughter in a community that has been engulfed in terrible pain for a year.

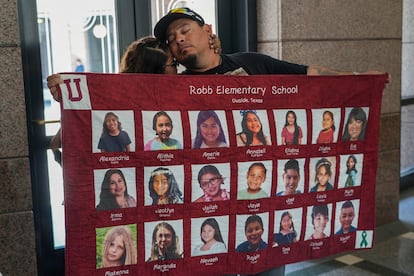

On the surface, everything has changed. The town, where eight out of 10 people are of Hispanic origin, has become a tribute to the lives destroyed by an 18-year-old armed with an AR-15, who broke into class on the last day of school. Large murals pay homage to the deceased children and teachers. Nine-year-old Jackie Cazares is painted next to the Eiffel Tower, because she always wanted to see Paris. Rojélio Torres is seen surrounded by Pokémon. Elihana García poses next to him with a basketball team jersey and her favorite junk foods: Maruchan ramen and spicy flavored Takis chips.

But in reality, very little has changed. Anger and disappointment are eating away at the families of the victims, who in the face of loss have become activists for tougher gun laws. This movement has proposed raising the minimum age to buy semi-automatic weapons — such as the AR-15 used in the shooting — from 18 to 21 years in Texas. The initiative has met with resistance from Republicans, who control the local Congress and oppose the measure, arguing it to be unconstitutional.

Verónica, who is originally from Mexico, but has spent three decades in Texas, says that the massacre changed everything for schools. Her Houston school now has a single front door, monitored throughout the day by a guard. Parents are prohibited from returning once they have dropped off their children. “No one goes to the bathroom alone anymore. We have a scheduled time when the whole class goes together,” she says, explaining how what happened in Uvalde has affected schools throughout the state. What’s more, teachers carry out two monthly drills where they pretend that a shooter has entered the school. A code is communicated through the speaker system. Door and window curtains are closed. The teachers gather their students in the place furthest from the door and keep quiet. “We have not had courses on how to shoot, nor have we discussed it. We don’t want it,” she says before being asked.

The families of the victims who have been calling for greater gun regulation suffered another blow earlier this month. The initiative to raise the legal age to acquire military-grade weapons in Texas advanced in a legislative commission with the vote of Democratic lawmakers and the support of two Republicans, but it was left off the legislative calendar because it arrived minutes after the deadline. On Sunday, Texas Congress passed a law that tightens surveillance of school districts to ensure that they have plans to respond to active shooter situations. Under the law, a school security body will have to review the security protocols and infrastructure of the centers at least once every five years.

“They have stalled it... they have played with our feelings,” says Jesse Rizo, a relative of Jacklyn Cazares, one of the children killed in the massacre. “I’ll be honest, we’re just a number [to politicians]. We’re just a statistic. So many weapons are sold. They’re controlled by the NRA, they’re controlled by big money. And they say, ‘Well, we sell so many weapons. We expect a loss of this amount. We expect to have so many people get killed.’ It’s all a numbers game to them,” says Rizo. “Common sense tells you that you can’t have kids and innocent people dying at the mall, at schools, at Walmart. It’s just not normal for that to happen, right? Why is it the people in power aren’t saying, ‘let’s make some changes’?” In front of him, on a table, there is an image of his niece-in-law at her first communion. Ten days later, Jacklyn was buried in the same white dress she wore to the event.

The families of the victims have found little support in the Texas Capitol in Austin. One of the few politicians supporting their cause is Democratic Senator Roland Gutiérrez. They believe that he joined their cause because he is one of the few parliamentarians who watched the complete videos of the massacre from the Department of Public Safety. Last Thursday, in an emotional speech, Gutiérrez admitted that politicians had failed to improve security at schools. “They gave me a hard drive this size with two terabytes,” he said, holding up a cell phone. “What I saw were little children with no faces. What I saw was bodies just riddled, riddled [with bullets]. Blood everywhere. Three piles of kids... Two of them in one room, kids in another… Because that’s what we train them to do. We trained them to go huddle together. I know you think that we have done some good things on school hardening, and we have [...] but it is hardly enough,” he declared with a broken voice.

The Uvalde massacre is far from the last tragedy to hit the United States. Last year was the second most violent year, with 647 mass shootings, second only to 2021. In 2022, some 1,683 minors died from gun violence. So far in 2023, 675 children and teenagers have died. The most recent shooting in Texas happened on May 10. It took a man of neo-Nazi ideology four minutes to kill eight people and injure seven in a shopping center on the outskirts of Dallas.

Waiting for demolition

Robb Elementary has become a depressing tourist spot in Uvalde. The school — which had been welcoming Mexican-American students since the days of segregation in the 1950s — is now abandoned and awaiting demolition. The windows are boarded up, and the building is surrounded by a black mesh. On the sidewalk there are 21 white crosses decorated with sunflowers and the names of those who died. Hundreds of rosaries hang from another large crucifix. The site, which will become a memorial, is guarded by two state patrol cars. In the rest of the schools in the district, fences almost two meters high have been installed.

“You feel sad,” says Joel Mata. He and his family drove 200 miles from their home in Houston to attend a graduation in San Antonio. They then traveled two more hours to Uvalde. They wanted to understand what happened. His wife, Verónica, is a second grade teacher. “I wanted to see where the gates were and understand what could have been at fault,” says the teacher. The Uvalde shooter entered the grounds via an unlocked back door.

Daniel García, a retiree who lives in the neighborhood where the school is located, says that many people come looking for answers. The killing, he says, has brought the community closer together. With the exception of a couple of families of the victims, the vast majority remain in Uvalde. It is taboo to talk about Salvador Ramos, the shooter, who was killed by Border Patrol officers after more than an hour of inaction from hundreds of law enforcement officers. “No one says his name, it’s as if he never existed,” says García. The community pushed out the shooter’s mother, Adriana Martínez, from town. The last anyone heard from her was that she had moved to Oklahoma. In January, she was arrested for threatening to kill the man she lived with.

As soon as he turned 18, Ramos bought an AR-15 from Oasis Outback, a store and restaurant in the city. The business has stopped selling the controversial model “for the moment,” according to a store worker. The rifle fired 142 rounds on that fateful morning. The online newspaper Texas Tribune published a report based on the audio from the body cameras of some of the nearly 300 police officers who responded to the emergency. Some of the officers were reluctant to act out of fear of the AR-15. “He has a battle rifle,” one voice is captured saying. “What’s the safest way to do this? I’m not trying to get clapped out,” said a state trooper, who was one of the first to arrive at the school.

The Uvalde school shooting put the AR-15 at the center of the gun control debate in the United States. President Joe Biden wants to ban all assault weapons across the country, a move that is opposed by Republicans. The massacre, however, sent shockwaves across the country. In April, the state of Washington became the 10th state to outlaw sales of assault weapons.

The massacre led to the firing of several police officers, the dismissal of municipal commissioners and the early retirement of school district officials. The children’s families are still calling for other officials — who failed to act on the day of the shooting and remain in their positions today — to be removed from office. They know that none of this will bring their children back, but they are trying to find some meaning after the loss. “Justice can be defined in many ways,” says Jesse Rizo. “It’s getting someone to resign or to face charges in court. But justice is also that we are told the truth. The shooter was solely responsible, right? But for me, the worst thing that happened is how all this was handled. That is the big problem.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.