Soccer coach Pep Guardiola used a tax amnesty to regularize an account he held in Andorra

The Manchester City coach was depositing his salary there while playing at a team in Qatar, and failed to declare it to the Spanish Tax Agency while managing FC Barcelona

Josep “Pep” Guardiola, an iconic figure at FC Barcelona and one of the most-lauded soccer managers in the world, had a current account open in the principality of Andorra until 2012, when he took advantage of a tax amnesty in Spain introduced by then-prime minister Mariano Rajoy’s conservative government to regularize his fiscal situation. Until that point, the current coach of Manchester City had not declared the funds held in the account to the Spanish Tax Agency.

Lluís Orobitg, who is Guardiola’s tax advisor, explains that his client only used the account at the Banca Privada d’Andorra (BPA) to deposit the salary that he earned when he was at Al Ahli, the Qatari club where he played between 2003 and 2005. When he took advantage of the tax amnesty, the sportsman regularized nearly €500,000, paying a levy of 10% on the interest that the funds had generated over the previous four years, given that previous years had exceeded the statute of limitations. (Under Spanish law, the Tax Agency can only go back four years from the date a tax return should have been submitted to review how much tax should have been paid.)

Pep Guardiola’s name can be found in the Pandora Papers, a collaborative investigation coordinated by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). More than 600 journalists from 117 countries have spent the last two years analyzing 11.9 million leaked documents from 14 firms of lawyers specializing in creating offshore companies in tax havens.

This type of company, based in countries different from those where their administrators reside, are legal provided the owner declares them to the tax authorities in their place of residence. For the authorities, the problems begin when the owners are seeking anonymity, zero taxes or to launder money in these jurisdictions.

In Spain, EL PAÍS and television network La Sexta have analyzed the leaked documents in search of public figures of interest who have taken advantage of some of the world’s most opaque tax havens. The result is more than 700 companies linked to this country, among which can be found dozens of relevant personalities.

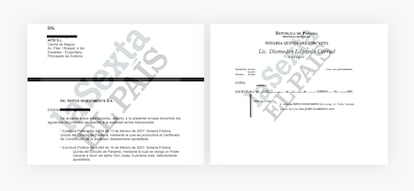

The name of Josep Guardiola i Sala, who is aged 50, appears in a document from Alemán, Cordero, Galindo & Lee (Alcogal), one of the offshore service providers at the center of the Pandora Papers investigation. He is listed as the legal representative of the Panamanian company, Repox Investments. The company was set up in February 2007, following Guardiola’s retirement as a professional soccer player, and four months before he was appointed the coach for the Barcelona B reserve team. Orobitg explains that the existence of Repox has nothing to do either with the Barcelona soccer club or with the business interests of Guardiola in Panama, and that the company had no activity. It served practically as a shell company to hide the real owner of the funds in Andorra.

The creation of Repox was, according to the tax adviser, an initiative from the Andorran bank to safeguard the identity of the coach as the bank account holder. The use of the extra layer of opacity offered by this kind of shell company was a common practice at that time in Andorra, according to sources from the Tax Agency.

Involved in the setting up of the company was Afsi, a small asset manager created in 1997 by the oldest private bank in Andorra, Andbank. Afsi, which was active at least until 2018, has a key role in the Pandora Papers, and counted on dozens of Spanish citizens among its clients, specializing in the creation of companies in jurisdictions such as the Virgin Islands, Belize, the Bahamas and the Seychelles. In Guardiola’s case, the Panamanian law firm Alcogal sent the documents related to the company’s creation and its articles of incorporation to Afsi, as indicated in the documents analyzed by EL PAÍS.

After leaving Barça in 2001 and following stints in the Italian league, Guardiola was signed as a player for Al Ahli in Qatar in 2003. According to news reports, he was paid just over €2 million a season. During his first season there, he was voted Best Foreign Player. The creation of the account in Andorra dates back to his time in Qatar. Orobitg explains that the decision to open the account in Andorra was due to the impossibility of obtaining a residency permit in that country, where he would not pay taxes. The then-player decided to deposit his salary in Andorra, a country with a more favorable fiscal regime and where he would not have to pay any tax because he was not a resident there either. His consultants explain that he did not deposit the funds in Spain because they feared that, without a residency permit in Qatar, the Spanish Tax Agency could object to him filing his tax returns as an expatriate when in reality he played and lived in the Emirate during those two years.

Barça coaching job

In 2007, Guardiola switched to coaching and began to manage the reserve team Futbol Club Barcelona B. The next year he moved to the main team, FC Barcelona, staying in the role until the summer of 2012. During these years at the helm of Barça, which saw him lead the team to two Champions League titles and three league trophies, he kept the account open in Andorra, without declaring it to the Spanish Tax Agency. Nor did he declare the interest from the funds, despite the fact that the manager was now living in Spain. In April 2012, during the worst of the global financial crisis, the Popular Party (PP) government of Mariano Rajoy approved the tax amnesty. And the soccer manager, on advice from his advisors, took advantage of the situation to declare the money to the tax authorities.

The Special Tax Declaration (DTE), as the Rajoy government called the tax amnesty, was a window opened by that administration to allow companies and citizens to bring to light undeclared funds, which were subject to a 10% levy – much lower than the rates that would have been applicable if the money had not been hidden. The aim of the government was to raise €2.5 billion. The process, however, was a disaster. The Tax Agency was forced to relax the requisites and ended up collecting half of what was forecast.

According to the documents consulted by EL PAÍS, Guardiola filed form 750 to the Tax Agency – the document used for the tax amnesty – and regularized nearly half a million euros. This figure corresponds to the interest from the money that had accumulated in the account between 2007 – the last year that was subject to scrutiny by the Tax Agency – and 2010, which is why it was subject to the 10% tax rate. He did not have to pay anything on the salary he earned for the two seasons he spent at the club in Qatar, given that it fell outside the statute of limitations. This newspaper has been unable to determine the full sum of money held in Andorra nor the exact date the account was opened.

The PP’s tax amnesty proved controversial, given that it gave many tax evaders the chance to launder their money at a reduced cost. The process irritated tax inspectors and ended up being annulled by the Constitutional Court. But it was taken advantage of by more than 30,000 people, most of them business figures.

Among the few names that came to light related to the process were political leaders and the owners of some of Spain’s biggest fortunes: Rodrigo Rato, former deputy prime minister of the central government and former managing director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF); Francisco Granados, former right-hand man of Esperanza Aguirre, the Madrid regional premier between 2003 and 2012; Diego Torres, former partner of King Felipe VI’s brother-in-law, Iñaki Urdangarin, who is still serving out his five-year sentence for embezzlement; José Ángel Fernández Villa, former mining leader in the General Workers Union (UGT); the brothers Antonio and Jorge Gallardo, owners of Almirall pharmaceutical laboratories; Ildefonso Falcones, best-selling writer and author of La Catedral del Mar (or, Cathedral of the Sea); and Oleguer Pujol Ferrusola, the son of the former Catalan regional premier, Jordi Pujol.

It wasn’t just politicians or business leaders with legal problems that took advantage of this process, but also hundreds of small business leaders or people with assets in other countries who had not updated their situations with the Tax Agency, as was the case with Guardiola.

The tax amnesty offered by the government was coupled with the disappearance of opaque financial structures created abroad before the end of 2012. According to the sources consulted, this explains why Guardiola’s Repox Investments was dissolved on December 21 of that year, which was also Guardiola’s last year as Barça’s coach. In January 2013, the Alcogal law firm sent Afsi the documents related to the company’s dissolution. A few days later, Bayern Munich confirmed Guardiola as the club’s coach: he would be paid €17 million a season.

The former Barcelona manager makes generous donations each year to non-profit organizations. Just last year, he sent €1 million to the Angel Soler Daniel foundation to help medical centers in the fight against the coronavirus. He has also made a number of donations to Activa Open Arms, the organization that rescues refugees from the Mediterranean. He has continued this altruistic activity with organizations in Germany, and now in the United Kingdom.

The government pardon – after the 10% payment – of those who had hidden money abroad did not stop the Tax Agency from opening inspections subsequently into a considerable number of people who had taken advantage of the amnesty. The Tax Agency did not investigate the presentation of the 750 form but it did use the data presented to investigate other irregularities. According to sources close to the soccer manager, Guardiola has not been subject to any inspection by the Spanish Tax Agency since 2012.

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.