Mexican drug cartels take aim at journalists

Threats against the press in Mexico are on the rise in an increasingly hostile and violent environment. In 2020, there were 692 attacks on reporters – 13.6% more than a year earlier – and six were killed

The Mexican press lives under constant threat. The latest episode took place last Monday: a group of armed members of the drug organization Jalisco New Generation Cartel stood in front of a camera, displayed their firepower and issued death threats against three national media companies – El Universal newspaper, Televisa broadcaster and Milenio daily – naming journalist Azucena Uresti in a video that swiftly flooded social media. The leader of the group, who all wore masks, spoke about the way his criminal organization was represented by these media outlets. He felt, he said, that what was being talked about did not reflect reality. With an assault rifle in his hand, he asked for fair coverage. Mexico is one of the most dangerous countries in the world for journalists, according to international watchdogs, but the message relayed on August 9 has set alarms bells ringing over an escalation of the dangers facing those who work in the press.

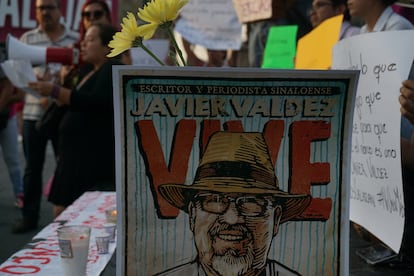

Threats to the safety of reporters in Mexico have been a constant for over two decades. Some of them have been carried out and the number is increasing: since 2004, at least one journalist has been killed each year. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) has recorded the assassinations of 129 reporters since 1994 over matters related to their work.

At this point in time, no threatening message can be taken lightly. According to Leopoldo Maldonado, director of the organization Artículo 19, which monitors the right to press freedom, the latest message from the cartels should serve as a wake-up call for the Mexican government. “This is an escalation in itself in the context of an upward spiral of attacks against the press and if there is no response from the state it could lead to yet more violence,” he says. In 2020, Artículo 19 recorded 692 aggressions toward journalists – a 13.6% rise over 2019 – of which 154 were threats of various kinds. Last year, six Mexican reporters were assassinated.

“Criminal organizations feel emboldened by the lack of state action,” says Maldonado. Crimes against journalists are also a reflection of the reality in a country where 98.5% of them go unpunished. Maldonado points to a “permissive context” in which those who carry out attacks on reporters know they will not face any consequences because the ability of the Mexican authorities to investigate, identify the culprits, try then and sentence them is severely diminished.

“The message is abundantly clear: you can attack a journalist and you won’t end up in prison,” says Adela Navarro, editor of Tijuana-based daily Semanario ZETA, whose journalists have been under constant threat for two decades and which has seen some of its contributors killed. Navarro points to the historical fragility of the media in Mexico’s outlying states, where far from the hustle and bustle of Mexico City they are regularly threatened and coerced over control of their coverage while receiving little support. “We are accustomed in this country, where impunity reigns, that in the states where criminals have established their mafia territories, journalists will be threatened, harassed and killed. But they had never crossed the line of the national media,” she says.

The press fragility, Navarro highlights, is already evident in media content: areas where the cartels hold sway, like Tamaulipas and Chihuahua, have become walls of silence where information flows in dribs and drabs.

The message sent out by the Jalisco New Generation Cartel specifically mentioned coverage of the battle the organization is waging in Michoacán – a key region for drug trafficking – against other criminal organizations for control of more or less everything that happens there. John Holman, the Mexico correspondent for the news channel Al Jazeera, explains that he spent months looking into the possibility of embedding himself in Michoacán to relay the complex criminal status quo in the state to an international audience. In June, he published a report after more than three months of work in which he acknowledged the help of local reporters was vital. “There is a lot of fear and with good reason. While we come and go, they remain there. The risks are far greater for them,” he says. “We spoke to [local] journalists who told us that they no longer cover drug trafficking issues because they live there and the risks for them and their families are too great. I would do exactly the same thing. It is a huge privilege, I guess, to be part of an international [press] organization, which allows us to do these kinds of reports without running the same risks ourselves.”

Navarro says that in order to protect her journalists some stories related to the cartels carry the generic byline “Zeta Investigations,” a practice that some national publications have also adopted in recent years. Holman notes that media companies based in Mexico City tend to have better means of protection for their correspondents. Reporters based in regions with high levels of criminal influence consulted for this report refused to speak about conditions in the places where they carry out their work for fear of reprisals.

Aggressors do not always carry a weapon or work for the cartels. In over half of the crimes against journalists recorded by Artículo 19, those seeking to silence the reporter in question were public officials. The majority of them occupied posts in municipal or state government. Maldonado explains that his organization has found it more difficult to register attacks carried out by the criminal groups because the victims and their families fear for their lives. However, he adds that the threats from public administrators tend to be linked to the world of organized crime. “In five of the six assassinations we recorded last year, the local authorities were involved. They act in collusion and complicity with the criminal groups and it is becoming more and more obvious,” he says.

In 2012, Mexico set up the Mechanism for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders and Journalists, a platform funded by the state that seeks to guarantee the safety and security of reporters who are under threat. The effectiveness of this system has been questioned by a number of journalists after several were the victims of attacks despite supposedly being under its protection. Lydia Cacho has been one of the mechanism’s most vocal critics. Her work in exposing child trafficking networks led to a series of threats and the protection offered by the state has proven insufficient to guarantee her safety. Cacho spent several years in hiding in Mexico and now lives in exile. According to Mexico’s Secretariat of the Interior, 418 journalists were living under the protection of the system in 2020.

The message is abundantly clear: you can attack a journalist and you won’t end up in prisonAdela Navarro, editor of Tijuana-based daily ‘Semanario ZETA’

After the Jalisco New Generation Cartel’s threats against Azucena Uresti, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador publicly offered his support to the journalist. “You are not alone,” he said. Uresti confirmed that the government had contacted her shortly after the message was released to offer her protection. “I reiterate my solidarity with this journalist and with all journalists with the guarantee that our government will always protect those who carry out the profession of journalism. We will be by her side, helping her and protecting her,” López Obrador said.

However, the Mexican leader often uses the dais of the National Palace to criticize journalists. His words of support for Uresti were the exception to an official discourse that regularly stigmatizes the work of reporters. Since July, López Obrador has used the platform of his morning press conference to discuss the news that he and his team consider false or critical of his government. Without a professional verification system, the president singles out reporters by name and surname. Uresti, for example, was mentioned during one of these conferences weeks before the threats against her were made. “This is viewed by many [criminal] groups as carte blanche to attack journalists,” says Maldonado.

After a mention from the president, some journalists have received messages on social media ranging from jokes and insults to death threats. The one issued by the Jalisco New Generation Cartel was the most serious. In response, Uresti has continued to appear on the set of her nightly show. “We will carry on doing our job as we always have done,” she replied.

English version by Rob Train.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.