El Koki, the Venezuelan gang leader challenging Maduro’s security forces

Carlos Luis Revete controls a large Caracas neighborhood. The government blames the opposition for his rise to power, but organized crime has now gripped the capital for years

Almost all the houses in the upper part of Caracas’s Cota 905 neighborhood are full of bullet holes. Some of the marks are older than others, but many are recent – the traces of an ongoing war led by gangster Carlos Luis Revete, aka El Koki, against the Venezuelan state. Home to 700,000 people, Cota 905 is just three kilometers from President Nicolas Maduro’s office, and firmly under El Koki’s control, along with his right-hand men, Carlos Calderón “El Vampi” and Garbis Ochoa “El Garbis.”

In early July, criminals from El Koki’s gang waged a three-day gun battle against Venezuela’s security forces. According to the Monitor de Víctimas, a journalism initiative that reports on violence, 33 bodies were identified after more than 3,000 police descended on the area, along with reports of extrajudicial executions and robberies by police. At least 24 of those killed were victims of stray bullets or did not belong to any criminal group. Five were civil servants, while just four were actual criminals, according to local media.

The Venezuelan press has documented at least 58 deaths in six major police operations carried out since 2015 to capture the gang’s ringleaders. All have failed. After four years in which the police did not set foot on Koki’s turf, in 2021 they have launched no fewer than three attempts to capture him. The government has now offered a $1.5 million (€1.2 million) reward for information leading to the capture of El Koki, El Vampi and El Garbis.

At 43 years old, Revete is an outlier for those who study violence in Venezuela. Living longer than your 25th birthday – the average life expectancy for criminals in the poorest areas of the country – is highly unusual. El Koki also has a rap sheet including several police murders, an arrest warrant outstanding since 2012 and the distinction of never having served jail time, all of which have transformed him into a grimly legendary figure. His gang is dedicated to kidnapping, drug trafficking and car theft, with the modus operandi of killing and setting fire to his victims. The videos can be viewed on social media.

In 2012, the government implemented a policy of “peace zones,” including in Cota 905, to try to pacify urban and rural gangs. Cota 905 residents say Koki used that time to kill off his rivals and establish alliances to form a mega-gang, a criminal organization with more than 60 foot soldiers armed with heavy-duty weapons. This has also happened in the most violent cities of Mexico or Brazil, and in Caracas alone there are five other such areas totally abandoned by the state, according to the criminologist Fermin Mármol García.

The “peace zone” program encouraged criminals to give up their weapons in exchange for financial incentives to run legitimate businesses, while the gangs insisted the police stay away. “The plan ended up being oxygen for criminal entities,” explained Mármol García. Media investigations have shown that some gangs simply used the money to buy more powerful weapons. “Where the state has abandoned its presence and functions, criminals run micro-states,” he added.In 2015, the Venezuelan security forces launched Operation Liberation of the People, with military and police raids in the neighborhood. They killed 15 people, most of them innocent.

The United Nations Independent Fact-Finding Mission investigated those raids last year and found that El Koki was able to bribe police officers to give him advance notice of the operations. The journalism non-profit InSight Crime has reported that Venezuela’s Vice-President Delcy Rodríguez agreed on a truce with the Cota 905 gang when she visited in 2017, which held until recently. But El Koki is still receiving warnings of police movements, and no one higher up in the gang was captured in the most recent raid.

Prisoners in their own homes

El Koki’s territory is strategic, and he keeps a tight grip. “In Cota 905 you cannot sell your house to a person they [the gang] do not know,” said one resident, who has crossed Koki in the street several times, and asked to remain anonymous due to safety fears. In some parts of the neighborhood there are gates for which only the gang leaders have a key. When locked, everyone is imprisoned inside the perimeter. On the other hand, when the water or gas stops flowing, or food aid from the government fails to arrive, a simple phone call from a gang member solves the problem. “At least these punks don’t steal from you,” the resident added.

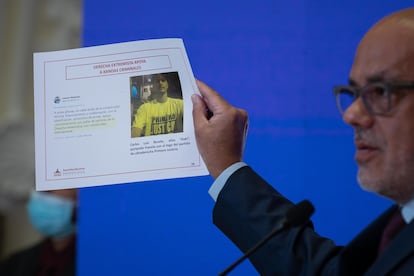

Amid this total absence of the state, Maduro’s government instead blames the opposition for what is happening in neighborhoods like Cota 905. Last week it imprisoned Freddy Guevara, the closest collaborator of opposition leader Juan Guaidó, and is pursuing other politicians over the fallout from the failed raid. From her balcony, a neighbor recounted what she saw the day police arrived. “It was the first time that the thugs came down from the neighborhood riding in pickup trucks, perfectly organized,” she said.

Like everyone else in the area, she lives in fear and requested anonymity to speak freely. That night, she organized a pajama party with her children, aged eight and two, to disguise the noise of the gunshots: “I let the older one play with the PlayStation the whole time, so he wouldn’t notice the war that was going on outside.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.