How a vast network allowed Venezuela to evade US oil sanctions

A joint investigation by EL PAÍS and Armando.info unveils the inner workings of a scheme involving dozens of individuals and companies that illicitly sold crude and transferred the money through tax havens in a shady multi-million-dollar business

The oil-for-food scheme

Since 2014 the US has been imposing economic sanctions on Venezuela to strangle the Maduro government

1

The US sanctions

Maduro

government

Oil

PDVSA

The US closes off the international market for Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA). The country loses its main source of foreign currency.

Money

2

The Venezuelan government

bypasses the sanctions

PDVSA

The Maduro government uses the Russian oil companies' routes to keep selling its crude to other countries

Payments are made in euros or rubles to bypass US banks

Russia

India

China

Iran

3

Venezuela needs new partners

PDVSA

The Mexican company Libre Abordo strikes a deal to exchange corn and drinking water tanker trucks for PDVSA oil

Mexico

4

The scheme extends futher

At a more advanced stage, Mexican trading firms signed contracts offering to take the oil out of Venezuela and resell it

Money

China

Singapore

Malaysia

Iran

Bangladesh

Palestine

India

Source: In-house.

N. CATALÁN / EL PAÍS

The oil-for-food scheme

Since 2014 the US has been imposing economic sanctions on Venezuela to strangle the Maduro government

1

The US sanctions

Maduro

government

Oil

PDVSA

The US closes off the international market for Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA). The country loses its main source of foreign currency.

Money

2

The Venezuelan government

bypasses the sanctions

PDVSA

The Maduro government uses the Russian oil companies' routes to keep selling its crude to other countries

Payments are made in euros or rubles to bypass US banks

Russia

India

China

Iran

3

Venezuela needs new partners

PDVSA

The Mexican company Libre Abordo strikes a deal to exchange corn and drinking water tanker trucks for PDVSA oil

Mexico

4

The scheme extends futher

At a more advanced stage, Mexican trading firms signed contracts offering to take the oil out of Venezuela and resell it

Money

China

Singapore

Malaysia

Iran

Bangladesh

Palestine

India

Fuente: In-house.

N. CATALÁN / EL PAÍS

The oil-for-food scheme

Since 2014 the US has been imposing economic sanctions on Venezuela to strangle the Maduro government

1

The US sanctions

Maduro

government

Oil

PDVSA

The US closes off the international market for Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA). The country loses its main source of foreign currency.

Money

2

The Venezuelan government bypasses the sanctions

PDVSA

The Maduro government uses the Russian oil companies' routes to keep selling its crude to other countries

Payments are made in euros or rubles to bypass US banks

Russia

India

China

Iran

3

Venezuela needs new partners

PDVSA

The Mexican company Libre Abordo strikes a deal to exchange corn and drinking water tanker trucks for PDVSA oil

Mexico

4

The scheme extends futher

At a more advanced stage, Mexican trading firms signed contracts offering to take the oil out of Venezuela and resell it

Money

China

Singapore

Malaysia

India

Iran

Bangladesh

Palestine

Fuente: In-house.

N. CATALÁN / EL PAÍS

The oil-for-food scheme

Since 2014 the US has been imposing economic sanctions on Venezuela to strangle the Maduro government

Venezuela needs

new partners

The scheme extends

futher

The US sanctions

The Venezuelan government

bypasses the sanctions

1

2

3

4

Maduro

government

PDVSA

PDVSA

China

India

Singapore

Oil

Payments are made in euros or rubles to bypass US banks

Malaysia

PDVSA

Mexico

Iran

Bangladesh

Palestine

Money

Money

Russia

India

China

Iran

The US closes off the international market for Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA). The country loses its main source of foreign currency

The Maduro government uses the Russian oil companies' routes to keep selling its crude to other countries

The Mexican company Libre Abordo strikes a deal to exchange corn and drinking water tanker trucks for PDVSA oil

At a more advanced stage, Mexican trading firms signed contracts offering to take the oil out of Venezuela and resell it

Source: In-house.

N. CATALÁN / EL PAÍS

On March 7, 2019, Venezuela was plunged into darkness. What most assumed was just another blackout lasted an hour, then another, and continued: one day turned into two, and then three. President Nicolás Maduro immediately blamed an act of sabotage by the United States, but his administration also quickly and quietly contacted a group of partners, many of them Mexican, that it has worked with for decades. What they agreed might have appeared at first to be a fix for Venezuela’s energy woes, but it has transformed into something much larger: an international network operating under the guise of humanitarian aid to move huge amounts of oil, money and other resources, including gold, coal and aluminum. The aim, which has largely succeeded, was to avoid sanctions imposed by the United States.

An investigation by EL PAÍS and Armando.info can now reveal how this scheme involving dozens of people and companies across 30 different countries moves money through tax havens. The evidence collected from thousands of documents and dozens of interviews, including some of those involved in this multi-million dollar business, sheds light on how this opaque network was created and how it later expanded. Most sources spoke on condition of anonymity due to fear of reprisals.

The origins of the scheme stretch back to the sanctions imposed on Venezuela since 2014, mostly by the US, against “those responsible for significant acts of violence, serious human rights abuses, or antidemocratic actions” in the country. Pressure on the regime was ramped up in January 2019, when the US recognized opposition leader Juan Guaidó as interim president. The Donald Trump administration went on to impose sanctions on Venezuela’s state oil company (Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A., or PDVSA) and the central bank, in a failed attempt to pressure Maduro to leave power.

A month after Venezuela’s energy meltdown, Vice-President Delcy Rodríguez picked up the phone and called a group of Mexican business associates who were well placed in the energy sector. The idea was supposedly to discuss the acquisition of generators of a type used in the Iraq War, in order to alleviate Venezuela’s electricity shortages. But from the first trip the businessmen made to Caracas, it was clear that the intention was to create something much bigger. Several members of the Venezuelan government and operators of the Chavista regime sowed the seeds of an international plot to generate money that would leave no trace.

Today, sanctions are a bargaining chip used between the opposition and the Maduro government to find a way out of the country’s long-running political crisis. Sanctions have reduced the government’s ability to do business with many companies over fears of retaliation by the US Treasury Department. In a country with one of the world’s largest oil reserves, PDVSA is Venezuela’s main source of foreign-exchange earnings. When PDVSA suffered from a shortage of revenue that the government badly needed, the administration resorted to paying in crude instead of cash.

The scheme first exchanged oil for food and water tankers, but then expanded to earn money from exports via financial networks beyond the reach of the United States. All those involved in the scheme are linked to one person: Alex Saab. He is allegedly Maduro’s front man and is currently in Cape Verde, awaiting extradition to the US to be tried on money-laundering charges. In Caracas, Vice-President Rodríguez was instrumental in activating the Mexican connection. Her brother Jorge is currently the president of Venezuela’s National Assembly, and together they form a power duo that has replaced former parliamentary speaker Diosdado Cabello as the unofficial second-in-command in Venezuelan politics. In April 2019, following the mass blackouts, Rodríguez organized a series of meetings between government officials and pro-Maduro facilitators on one side, and Mexican businessmen on the other. This latter group included José Adolfo Murat, an entrepreneur and politician. The vice-president had met these individuals at international political gatherings such as the Forum of Biarritz.

Former economy minister Simón Zerpa (now facing accusations of disloyalty) attended a discussion about acquiring drinking-water tankers, and enquiries were made about securing a favorable spot in the Mexican port of Veracruz that would act as a gateway to send and receive large shipments in and out of Mexico.

The next meeting in Caracas was attended by Ricardo Morón and José Luis Sandoval. Morón was sanctioned by Washington in July 2020 for aiding President Maduro’s son, Nicolás Maduro Guerra, in his illicit business activities. A US Treasury Department statement says Morón and his brother Santiago “are trusted partners of Nicolas Maduro and his son”. Sandoval, meanwhile, is a PDVSA official who mooted the possibility of trading wheat and corn through Colombia, with the price set and payment made in gold. Present at yet another meeting was Omar Nassif, the brother of a businessman who is close to Vice-President Rodríguez. Nassif suggested moving foodstuffs through Colombia while conducting financial transactions via Hong Kong, and assured the assembled company he had some trusted suppliers in Mexico. Nassif had also participated in the CLAP food distribution scheme touted by Maduro in Venezuela, which has also been mired in corruption allegations.

Main players in the network

Government of Venezuela

Delcy

Rodríguez

Vice-President

Nicolás

Maduro

President

Tareck

El Aissami

Oil Minister

PDVSA

CORPOVEX

Venezuelan Corporation

of Foreign Trade

Facilitator

Álex Saab

Alleged frontman

CLAP* business

Entrepreneurs

J. L. Sandoval

Ricardo Morón

Omar Nassif

CLAP*

business

Oil for Food

Program

Entrepreneurs

Mexican

entrepreneurs

Alessandro Bazzoni

Joaquín Leal

Philipp Apikian

Verónica Esparza

(mother)

Francisco D’Agostino

Olga Mª Zepeda Esparza

(daughter)

ELEMENTO

SWISSOIL TRADING

LIBRE ABORDO

SCHLAGER BUSINESS

WASHINGTON TRADING

ALEL TECHNOLOGIES

Maritime and

Financial

Intermediaries

LUZY TECHNOLOGIES

COSMO RESOURCES

OVER 50 ENTITIES

IN 30 COUNTRIES

Final clients

PetroChina

Sinopec

Refinerías en Asia

*Subsidized food parcel distributed by CLAP

(Local Committee for Supply and Production)

Fuente: In-house.

EL PAÍS

Main players in the network

Government of Venezuela

Delcy

Rodríguez

Vice-President

Nicolás

Maduro

President

Tareck

El Aissami

Oil Minister

PDVSA

CORPOVEX

Venezuelan Corporation

of Foreign Trade

Facilitator

Álex Saab

Alleged frontman

CLAP* business

Entrepreneurs

J. L. Sandoval

Ricardo Morón

Omar Nassif

CLAP* business

Oil for Food

Program

Entrepreneurs

Mexican

entrepreneurs

Alessandro Bazzoni

Joaquín Leal

Philipp Apikian

Verónica Esparza

(mother)

Francisco D’Agostino

Olga Mª Zepeda Esparza

(daughter)

ELEMENTO

SWISSOIL TRADING

LIBRE ABORDO

SCHLAGER BUSINESS

WASHINGTON TRADING

ALEL TECHNOLOGIES

Maritime

and Financial

Intermediaries

LUZY TECHNOLOGIES

COSMO RESOURCES

OVER 50 ENTITIES

IN 30 COUNTRIES

Final clients

PetroChina

Sinopec

Refinerías en Asia

*Subsidized food parcel distributed by CLAP

(Local Committee for Supply and Production)

Fuente: In-house.

EL PAÍS

Main players in the network

Government of Venezuela

Delcy

Rodríguez

Vice-President

Nicolás

Maduro

President

Tareck

El Aissami

Oil Minister

PDVSA

CORPOVEX

Venezuelan Corporation

of Foreign Trade

Facilitator

Álex Saab

Alleged frontman

CLAP* business

Entrepreneurs

J. L. Sandoval

Ricardo Morón

Omar Nassif

CLAP* business

Oil for Food

Program

Entrepreneurs

Mexican entrepreneurs

Alessandro Bazzoni

Joaquín Leal

Philipp Apikian

Verónica Esparza

(mother)

Francisco D’Agostino

Olga Mª Zepeda Esparza

(daughter)

ELEMENTO

SWISSOIL TRADING

LIBRE ABORDO

SCHLAGER BUSINESS

WASHINGTON TRADING

ALEL TECHNOLOGIES

Maritime and Financial Intermediaries

LUZY TECHNOLOGIES

COSMO RESOURCES

OVER 50 ENTITIES IN 30 COUNTRIES

Final clients

PetroChina

Sinopec

Refinerías en Asia

*Subsidized food parcel distributed by CLAP (Local Committee for Supply and Production)

Source: In-house.

EL PAÍS

The name of Alex Saab crops up again. Saab “personally profited from overvalued contracts, including the [Venezuelan] government’s food-subsidy program,” the US Treasury Department has said, and between 2016 and 2018, Saab and his fellow Colombian Álvaro Pulido Vargas – whose real name was Germán Rubio; he changed it after being involved in a drug operation in 2000 – came up with the idea of a network of shell companies in Hong Kong, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates. These companies became linked to the Venezuelan scheme, and one of Saab’s advisors met with the Mexican businessmen in Caracas.

When the Mexicans returned home, they began to shape the Venezuelan government’s illicit network. Joaquín Leal, a 29-year-old businessman who was also sanctioned by the US Treasury Department in June 2020, then appeared on the scene, according to sources who spoke with EL PAÍS and Armando.info. At the time, Leal was working at Diversidad, Murat’s company, and together they began to develop the businesses proposed by the Venezuelans.

Murat would return to Caracas in May 2019 with Leal by his side to meet Zerpa, the economy minister, in search of certain clarifications. Initially payments were proposed in euros or rubles to avoid circulating money in US dollars, but a month later it was decided that food and drinking water would be exchanged directly for oil, with contracts drawn up in equivalent amounts of euros. A third party would make the payment, Zerpa said, with 70% made in advance. On the two contracts, worth €200 million, there is no account number written for the recipient to make the payment. Payments could be made “in installments,” with the possibility of terminating the contract within 90 days, the document states. The remaining 30%, according to the contracts, “will be processed by the buyer by competent financing entities,” without clarifying who that would be.

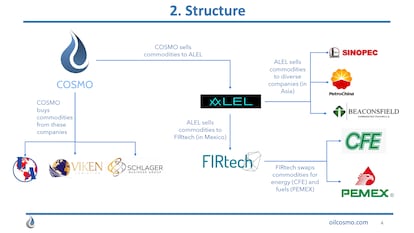

The various networks operated in 30 countries through more than 50 companies.

Fuente: In-house.

EL PAÍS

The various networks operated in 30 countries through more than 50 companies.

Fuente: In-house.

EL PAÍS

The various networks operated in 30 countries through more than 50 companies.

Source: In-house.

EL PAÍS

After signing the agreements, Leal sought advice and was in charge of obtaining the water trucks and coordinating the transfer of food from Mexico. He also negotiated the price of oil with his Venezuelan contacts. In emails he presented himself as the legal representative of Libre Abordo, the Mexican company with which the Venezuelan government had made the deal. After closing the deal, the Venezuelan oil company sent a series of invoices to Libre Abordo marked for the attention of Olga María Zepeda Esparza, the director and partner of the company. She was also sanctioned by the United States in June 2020. The emails detail the equivalent in barrels of oil and millions of euros that the oil company demanded as payment from the Mexican firm, besides some food and products in kind. For example, an invoice dated June 19, 2020 for €32.9 million (the equivalent of US $36.3 million) states that the oil was destined for Singapore.

This exchange of oil for food and water tankers was the trigger for the US Treasury Department to sanction Libre Abordo, Joaquín Leal and Zepeda Esparza a year later. Mexico’s Financial Intelligence Unit (UIF) then launched an investigation, but with few results. On May 18 of this year, the UIF filed a complaint with Mexico’s Attorney General’s Office, to which EL PAÍS has had access, requesting the seizure of a hundred accounts belonging to Libre Abordo, Leal, Zepeda Esparza and her mother, Verónica Esparza, who is a partner in the company.

The May 2019 trip was the only one that Murat and Leal made together to Caracas. Murat told this newspaper that he left the business in Leal’s hands and that he asked him not to proceed when informed that the business deal included an oil transaction. “I told him there were US sanctions in place and we couldn’t get into that mess,” Murat told EL PAÍS. He was unaware that Leal went ahead with the deal with Libre Abordo, he added. By the end of 2019, Murat said he broke off ties with Leal after learning he had gone ahead with the deal despite his warnings. Leal declined to respond to interview requests for this investigation.

Following the transactions involving drinking water tankers and corn, Leal went on to organize a secret network on behalf of the Maduro government, with the aim of selling Venezuelan oil outside the reach of US sanctions. He created dozens of companies interwoven with financial partners from 30 countries including Bangladesh, China, Curaçao, Greece, Luxembourg, Malta, Malaysia, Mexico, Norway, Singapore, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and United States, among other countries across three continents. Tax havens such as the Isle of Man and the British Virgin Islands were also used.

The provision of humanitarian aid was simply a pretext, this investigation found. The Mexican side would sometimes load up food onto ships and the Venezuelan state paid them in oil to take it out of the country. But behind this relatively simple operation was a more complex, and lucrative, set of calculations. PDVSA earned millions in profits through the resale of crude oil at below-market prices, with the earnings placed in Russian bank accounts, such as Gazprombank and Evrofinance Mosnarbank. In this manner, the state oil firm was able to carry out transactions outside the US banking system and without involving US citizens. The documents accessed by this investigation show that the oil deals took place between November 2019 and May 2020. In the vast majority of cases, the exchanges for food were forgotten and oil was sold directly to Mexican middlemen.

Once Libre Abordo agreed that the oil would leave Venezuela, it used a specific group of intermediaries for the resale of the barrels. It usually sought buyers from the same consortium involved in the scheme or else went to refineries located abroad. One shipment delivered to a Chinese company in Malaysia was resold by Orin Energy, a holding company dealing in raw materials. Leal and Libre Abordo’s main clients were in Asia, and corporate presentations state that two of the main buyers of Venezuelan oil were the Chinese oil firms PetroChina and Sinopec. Many of its shipments were sent to Singapore and Malaysia, two important Asian hubs for refining oil.

At first, Libre Abordo looked for clients in the world energy market. When it sanctioned the Mexican company in June 2020, the US Treasury Department noted that it used the same international routes, the same shipping processes and the same clients as two Swiss subsidiaries of the Russian oil company Rosneft had done in the past. The Russian giant was one of PDVSA’s main partners, but it exited the business in February 2020 after being sanctioned by the US for its dealings with Venezuela. Leal and his partners also consulted figures including Alessandro Bazzoni, an Italian with a long history of business dealings with PDVSA, and Philipp Apikian, a Swiss national who has also been involved in the sale and shipment of Venezuelan oil. Both were sanctioned in January 2021 by the White House as participants in the same scheme that has moved millions of barrels of Venezuelan crude under the radar of US sanctions.

One of the main intermediaries used by Leal to resell the Venezuelan crude was Elemento, a company incorporated in Malta by Bazzoni in March 2015, with subsidiaries in the Caribbean island of Curaçao and in the United Kingdom. The company had previously traded Venezuelan oil in association with a US firm. Between February and December 2019, Elemento managed at least 13 PDVSA shipments. Following his dealings with Leal, Bazzoni’s firm took over one of the first two shipments that Libre Abordo moved out of Venezuela. The goods resold by Elemento were delivered to a Macau-based company in Singapore in April 2020, almost a year after they set sail.

It was not the first time that Elemento had assisted the Maduro government in transporting hundreds of millions of barrels of oil, according to thousands of documents seen by EL PAÍS and Armando.info. To resell the shipments, Elemento contacted Swissoil Trading S.A., a Swiss energy company founded in 1998 that serves as a reseller of raw materials in the Middle East and Asia, and where Apikian is the sole administrator. With the intention of replicating the scheme devised by Elemento and reducing the losses and legal problems of going through other intermediaries to resell crude oil, Leal founded Cosmo Resources in Singapore on February 11, 2020. The idea, according to an organizational chart designed by Leal himself, was to share on the firm’s board of directors with his partner Bazzoni, and to continue selling the oil in Asia and other parts of the world.

The Mexican businessman explored the idea of absorbing Libre Abordo and its subsidiary Schlager Business Group, which was in charge of providing administrative support to the operations of its parent company, into Cosmo. On February 16, 2020, Leal wrote in an email that he was contemplating the idea of Cosmo buying Libre Abordo. A day later, Hugo Villaseñor, Cosmo’s chief financial officer and a close friend of Leal’s, coordinated the opening of a bank account for the firm. In an email sent to an executive of Alpha FX, a London-based foreign exchange bank that offers services internationally for “companies and institutions affected by currency volatility,” Villaseñor estimated that the monthly cashflow would range between €10 million and €40 million. The account was opened on the recommendation of Richard Rothenberg, Elemento’s chief financial officer.

Cosmo’s role is crucial in understanding how the Venezuelan government made money from oil behind the façade of humanitarian aid. In the application to open the account, the company explained that it derived its main income from payments made by PetroChina and Sinopec refineries for oil shipments leaving Venezuela. Other income came from payments made by other commodities brokers, such as Beaconsfield Commodities Trading, a Bazzoni consortium incorporated in Switzerland and with subsidiaries in the Cayman Islands, South Africa, Switzerland and Sweden. Cosmo, on the other hand, had its main cash outflows in payments made to Elemento and Libre Abordo, which were in charge of getting the oil out of Venezuela. One of Leal’s plans was to replicate the same business he had made with PDVSA with other Latin American oil companies, such as Mexico’s Pemex, Colombia’s Ecopetrol, and Ecuador’s Petroecuador.

Rosneft’s exit from Venezuela due to US sanctions sent Leal’s business to dizzy new heights. One of PDVSA’s main partners was gone, meaning the quantities of crude oil diverted to the Mexican network skyrocketed. By April 2020, the Mexican businessmen were receiving around 40% of the Venezuelan oil company’s exports, according to the US Treasury Department. As his business ventures took off, Leal began to worry about the legal status of his companies’ dealings with Venezuela. In December 2019, he approached US law firm Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP to seek advice, and in March 2020, a Mexican firm also issued its legal opinion on the possible sanctions potentially facing Leal and Libre Abordo.From Mexico, Leal structured various schemes to do business with Venezuela and used complex financial engineering to manage his assets and attempt to erase the money trail. Thousands of emails were exchanged between the members of Leal’s scheme, seen by EL PAÍS and Armando.info. They contain spreadsheets with the value of the crude oil and the monthly inflows obtained for selling the shipments, as well as export contracts, invoices for the purchase and sale of goods, and financial advisory services. There are also bank details, business plans exploring the possibility of entering the copper and aluminum markets, and a list of payments for the administrative costs of running the various firms in the network, including rent, utilities and international travel expenses.

One document recording income in 2019 shows the spectacular results of the dealings of a group of businessmen who were almost unknown prior to that year. Their five companies earned more than $107 million in 2019 alone, when they had not yet reached the peak of their success. Leal paid himself 750,000 pesos a month (just over US $37,000 or €30,500). His mother and sister made half a million pesos ($25,000 or €20,600 ), the highest-paid employees on payroll. His grandmother, meanwhile, earned 30,000 pesos a month that year ($1,500 or €1,200).

Leal and his entourage used at least 50 companies to hide the money trail, EL PAÍS and Armando.info have been able to verify, and each business plan had a linked company to carry out its projects. Leal appeared as a legal representative rather than a partner in most of these, and largely behind them were Verónica Esparza and her daughter Olga María Zepeda Esparza, or members of their family. Structures in tax havens also appeared in the thick portfolio, where the identity of the partners is hidden and cashflows can be disguised to avoid paying tax. One example is JLJ Technologies LLC, incorporated in Wyoming on March 20, 2019, where Leal was registered as sole administrator. The business did not have a particular function but allowed Leal to obscure the true operators of his firms.

The Mexican businessman also founded Mystic Universe, a company in the British Virgin Islands, which is the largest tax haven on the planet in terms of turnover and number of incorporated firms. Mystic Universe and a similar company in Ontario, Canada were registered by Leal in May 2019 in between his first trips to Caracas. The firms’ documents show that Leal owned 90% of the shares, while his mother, María Teresa Alfaro, and his sister, Carlota Jiménez, owned 5% each. On August 5, 2019, Mystic began operating as a holding company that absorbed control of other firms linked to Leal.

One of the filings prepared by Leal’s team states that Mystic invested in technology, energy and commodities companies in the Americas and beyond. “Mystic Universe’s objective is to change the world, so we focus on fundamental industries like energy, technology, commodities, finance and health,” the document states. On its old website, Mystic claimed to have invested more than $300 million. But all the beneficiaries of Mystic’s investments were other companies of Leal’s.

Mystic was presented as a Canadian investment fund in the Mexican media, focused on projects with a social impact. Articles published between August and September 2019 announced that the firm would invest in Hábitos Luzy, the Mexican subsidiary of Luzy Technologies, a company blacklisted by the US Treasury Department. On paper, the company specializes in providing health and nutrition advice through a mobile app, managing industrial canteens and reselling sanitary materials.

Leal, who constantly reshuffled his vast portfolio of companies through trusts, front companies and front men, even approached Morgan Stanley to explore an IPO for Mystic Universe on April 16, 2020, in just another of the many ploys enlisted by this vast network circumventing US sanctions against Venezuela.

Ewald Scharfenberg and Roberto Deniz are reporters for the Venezuelan investigation website Armando.info