Salvadoran migrant’s death in Mexico echoes killing of George Floyd

Victoria Salazar died after a Mexican police officer kneeled on her neck, but unlike the case in the United States which sparked widespread protests, her murder has become just another statistic

When the Salvadoran family of Victoria Salazar discovered a Mexican police officer had kneeled on her neck until she died, it was through Facebook.

The Mexican authorities made no attempt to contact Salazar’s family following her brutal killing on March 27 on the streets of Tulum, one of the most coveted tourist destinations in the Mexican Caribbean.

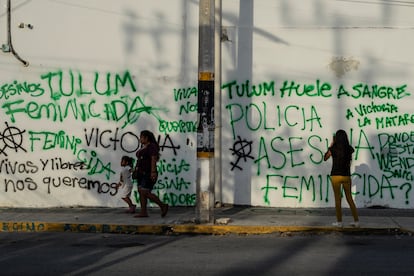

Since then, the incident has triggered a diplomatic spat with El Salvador, but protests have not erupted over police brutality as they did in the United States in response to the death of George Floyd, who was also killed after a police officer kneeled on his neck. Rather, Salazar has become another statistic in a country where 10 women are murdered every day.

Four police officers were attempting to arrest Salazar for alleged disorderly conduct when she was killed, and an image taken in her last moments of life shows her face down on the street with two officers leaning on her back and neck, and two others looking on.

Days after her death, on the street where Salazar was killed, life continues as normal. The only sign of what happened are some dried-up flowers scattered by the wind, a few burned-out candles and a sign with her name on it stuck to a post. A stark contrast to the massive protests seen in the US and worldwide after Floyd’s death.

You cannot see the crystal waters of the sea from the dusty neighborhood where she died, an area far from the beach and home to hospitality workers serving tourists from the US and much further afield. “The only reason my sister immigrated was in search of better opportunities, but of course, the violent situation in the country could have caused her to leave for reasons we don’t know,” says Salazar’s brother René Olivares when reached by phone by EL PAÍS. He mentions Salazar’s two daughters, aged 16 and 17, who have been left without a mother. “My nieces joined her in Mexico about two and a half years ago, but until then they lived with my mom and me,” Olivares explains.

Her brother only really knew the details of his sister’s life through his mother. Salazar worked in a hotel, she told him, and in one of the last conversations she had with her family by phone, Salazar told them she planned to settle permanently in Mexico. “She had spoken to my mom a little while ago to ask us for help for a piece of land she wanted to buy where she could build her house,” Olivares says.

In the street where she died, no one seems to have known her. At the tiny vigil, some curious locals approached to take pictures, but most of them adhered to the unspoken law of silence that prevails in working-class neighborhoods like this one. Nobody knew where she lived, who she was or what she did for a living. In this forgotten corner of a tourist paradise, the neighbors don’t speak with the new tenants, and focus on work. They leave early in the morning for long shifts by the sea and in the air conditioning of the luxury hotels, and late at night, they return home to hot concrete buildings to snatch a few hours of sleep.

Salazar arrived in Mexico about five years ago, according to her brother, fleeing misery and gang violence in El Salvador. She lived in Mexico’s Chiapas state for a while and then moved to Tulum with hopes of finding a job in the tourist town. Mexican authorities have since reported that she had a humanitarian visa, which granted her a status somewhere between a residence permit and refugee status and provided for a one-year stay in Mexico. But if she was fleeing violence in El Salvador, or the threat of it, the same misogyny caught up with her in Tulum.

According to CCTV footage from a store that leaked onto social media, Salazar was in an agitated state when the police pulled up. “The police arrived because she was very unsettled, they say she was throwing herself at cars. I just know that no matter how she was acting, she didn’t deserve to die that way,” says Amelia Magaña, a witness to the crime and recent arrival to the area after Hurricane Eta destroyed her home in Mexico’s Tabasco state last November. “When I saw she wasn’t moving, I grabbed my grandson and we ran home.” Others say that Salazar did not live in the neighborhood where she was killed, but in one of the illegal settlements collectively known in Mexico as invasiones or invasions. These slums consist of homes propped together from wood and sheet metal and have been popping up in the area, some spontaneously and others to force the regularization of land use for hotel construction later on. In any case, these are areas the police do not enter.

The day after his sister’s death, Olivares received a Facebook message from someone who knew her, and who had seen the video on social media. He watched the video. “It was her. At the time I doubted it though. I told my mom that it could be a scam, a bad joke,” he tells EL PAÍS. Soon after, the nightmare began. It was impossible for the family to avoid the images of their sister and daughter suffering as she died on the street. “When I see the video I feel immense pain, a lot of helplessness that I was not there to help her. But even though I feel bad that it is being shared, it is necessary for people to see it. We don’t want something like this to happen again,” says Olivares.

A death, a disappearance and a diplomatic conflict

Salazar’s death escalated into a diplomatic row between El Salvador and Mexico on the night of March 29, when the images of her treatment at the hands of the police were all over social media and television news. El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele demanded the Mexican government arrest not only the four police officers involved in Salazar’s death, but to find other possible suspects involved in her case. “There are more aggressors in this case, and also other victims. Not all the culprits have been arrested yet,” Bukele wrote in a message on Twitter. Mexico’s usually slow-moving prosecution system kicked into gear with unusual efficiency, in a country where less than 10% of crimes are solved.

The Mexican Foreign Affairs Ministry has since worked around the clock to ensure the rapid repatriation of Salazar’s body. In a joint effort with the Salvadoran authorities, the Olivares family are due to travel to Cancún to identify Salazar’s body in person, after only seeing photographs of her corpse in a morgue. Mexican prosecutors arrested and charged the police officers involved with femicide, and the local government in Tulum dismissed the head of the municipal police, the force responsible for her death. This was followed by an announcement by President Bukele that Salazar that one of her daughters were sexually abused by an ex-partner in Mexico, who was promptly arrested too.

Salazar’s death, which began with an all too familiar scene of police brutality, has escalated into a political standoff between El Salvador and Mexico, and an increasingly complex story. One of Salazar’s daughters, it was then announced, was missing. A few hours after a missing person’s alert went out, the Attorney General’s Office announced that she had been found.

After their mother’s murder, the two teenage daughters have become wards of the Mexican state. A day before the search warrant for the 16-year-old was issued, Olivares was hopeful that he would soon see his two nieces in Mexico: “We have spoken with them on Facebook and we want to decide together if they want to stay in Mexico or come back with us.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.