New AI models like ChatGPT pursue ‘superintelligence’, but can’t be trusted when it comes to basic questions

A study published in the journal ‘Nature’ warns that errors, even in simple matters, will be difficult to completely eliminate in the future

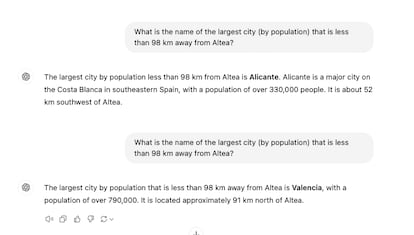

ChatGPT and other language models have become an increasingly common resource in a multitude of jobs. However, they have an underlying problem that tends to get worse: these systems often give incorrect answers. What’s more, the problem is getting worse.

“New systems improve their results in difficult tasks, but not in easy ones, so these models become less reliable,” says Lexin Zhou, co-author of an article published on Wednesday in the scientific journal Nature, which he wrote together with four Spaniards and a Belgian from Valencian University Institute for Research in Artificial Intelligence (VRAIN) of the Polytechnic University of Valencia (UPV) and the University of Cambridge. In 2022, several of the authors were part of a larger group hired by OpenAI to test what would become ChatGPT-4.

The article was reviewed for a year before being published, a common period for this type of scientific work. But outside of the study, the researchers also tested whether the new ChatGPT or Claude models have addressed this issue. “We have found the same thing,” Zhou says. “Or that it’s even worse. ChatGPT-o1 [OpenAI’s latest program] doesn’t avoid tasks and if you give it a handful of very difficult questions, it doesn’t say it doesn’t know, but spends 100 or 200 seconds thinking about the solution, which is very costly in terms of computation and the user’s time.”

It is not easy for a human to detect when one of these models may be making a mistake: “The models can solve complex tasks, but at the same time they fail in simple tasks,” says José Hernández-Orallo, a researcher at the UPV and another of the authors. “For example, they can solve several PhD-level mathematical problems, but they can get a simple sum wrong.”

It is a problem that’s difficult to fix as humans put increasingly challenging questions to the machines. “This discrepancy between human expectations of difficulty and the errors in the systems will only get worse. People will increasingly set more difficult goals for these models and pay less attention to the simpler tasks. This will continue if the systems are not designed differently,” says Zhou.

These programs increasingly avoid apologizing for not knowing an answer. This unrealistic confidence makes humans more disappointed when the answer turns out to be wrong. The paper proves that humans often believe that incorrect results to difficult questions are correct. This apparent blind confidence, coupled with the fact that the new models tend to always respond, does not offer much hope for the future, according to the authors.

“Specialized language models in medicine and other critical areas may be designed with reject options,” the paper says, or collaborate with human supervisors to better understand when to refrain from responding. “Until this is done, and given the high penetration of LLM use in the general population, we raise awareness that relying on human oversight for these systems is a hazard, especially for areas for which the truth is critical,” it warns.

According to Pablo Haya, a researcher at the Laboratory of Computational Linguistics at the Autonomous University of Madrid, speaking to SMC Spain, the work helps to better understand the scope of these models: “It challenges the assumption that scaling and adjusting these models always improves their accuracy and alignment.” He adds: “On the one hand, they observe that, although larger and more adjusted models tend to be more stable and provide more correct answers, they are also more prone to making serious errors that go unnoticed, as they avoid not responding. On the other hand, they identify a phenomenon they call ‘difficulty mismatch’ that reveals that, even in the most advanced models, errors can appear in any type of task, regardless of its difficulty.”

A home remedy

One home remedy for these errors, according to the article, is to adapt the wording of the prompt: “If you ask it multiple times, it will get better,” says Zhou. This method involves putting the onus on the user to get the question right or guess whether the answer is correct. Subtle changes to the prompt, such as “could you please answer?” instead of “please answer the following,” will yield different levels of accuracy. But the same type of prompt can work for difficult tasks and poorly for easy ones. It’s a game of trial and error.

The big problem with these models is that their presumed goal is to achieve a superintelligence capable of solving problems that humans are unable to handle due to their lack of capacity. But, according to the authors of this article, this path has no way out: “The current model will not lead us to a super-powerful AI that can solve most tasks reliably,” says Zhou.

Ilya Sutskever, co-founder of OpenAI and one of the most influential scientists in the sector, has just founded a new company. Speaking to Reuters, he admitted something similar: this path is exhausted. “We’ve identified a mountain that’s a bit different from what I was working [on]... once you climb to the top of this mountain, the paradigm will change... Everything we know about AI will change once again,” he said.

Zhou agrees: “In a way, he supports our arguments. Sutskever sees that the current model is not enough and is looking for new solutions.”

These problems do not mean that these models are useless. Texts or ideas that they propose without any fundamental truth behind them are still valid. Although each user must understand the risk: “I would not trust, for example, the summary of a 300-page book,” explains Zhou. “I am sure there is a lot of useful information, but I would not trust it 100%. These systems are not deterministic, but random. In this randomness they can include some content that deviates from the original. This is worrying.”

This summer, the scientific community was shocked when a Spanish researcher sent the European Data Protection Committee a page of references that was full of made up names and links, precisely in a document about auditing AI. Other cases have been taken to court, while many others have gone undetected.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.