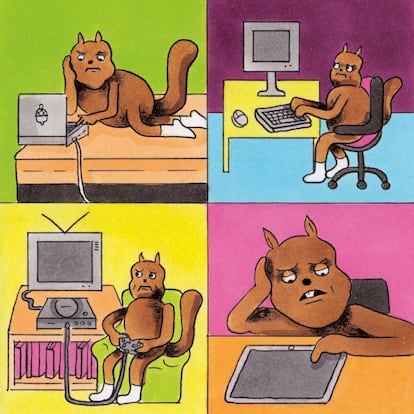

Why has the internet become so boring?

It is no longer a window to the world, nor an inexhaustible source of information, nor even a place to spend time discovering something curious or interesting. Instead, it is increasingly dull, uniform and unreliable

Everything seems too similar and there are hardly any new experiences. No more discovery and random connection with strangers (which is not the same as talking to a bot). Everything is repeated in an infinite loop by the work and grace of crazy algorithms that pressure us to adopt identical formats — first selfies, now reels, then who knows what next — and talk (if we fight, so much the better) about the same topics. The price of resistance is irrelevance. Don’t you often feel like you’ve spent two hours on the internet without really knowing what you’ve been doing? Aza Raskin created the infinite scroll in 2006, and in 2018, he admitted in a BBC interview that he regretted it: “It’s as if they’re taking behavioral cocaine and just sprinkling it all over your interface and that’s the thing that keeps you coming back and back and back.”

We are more alone than ever. Where are the friends? Why doesn’t anyone talk to me? In 2010, social networks underpinned social life, opened the door to new friends and reconnected us with others we thought we had lost. It was the golden age of web 2.0. Now Facebook is a wasteland; Instagram, a farm of narcissists, and TikTok puts out content at such a speed that it barely allows for human interaction. Video essayist Eleanor Stern (100,000 followers on TikTok) believes that the problem is that social networks are much more hierarchical now: on the one hand, there is the audience; and on the other, the creators. And they are two worlds that do not mix.

We also don’t trust Google’s answers. You shouldn’t trust the first page of Google too much. What is top ranking is not always entirely trustworthy. If today you ask Google how to remove a wine stain from the carpet, thanks to SEO, the search engine will spit out vague answers that do not necessarily come from a personal experience, but rather from content optimization rules. In fact, the answers will probably be copies of other posts, which you will also find on the first page. There are no longer useful answers if someone hasn’t monetized them. And if they have monetized them, they probably want to sell you an anti-stain product. Start trusting the results from the third page or, better yet, ask your mother, a friend or take the carpet to the cleaner.

There is a lot of pressure (we have become too serious). Now you have to think and work more before publishing something online. It is the death of the silliness and spontaneity that have made us laugh so much online. “Instagram started the era of online self-marketing with selfies, but then TikTok and Twitch accelerated it. Selfies are no longer enough; video-based platforms showcase your body, your speech and mannerisms, and the room you’re in, perhaps even in real time. Everyone is forced to perform the role of an influencer,” writes journalist Kyle Chayka in The New Yorker. But the standards are too high and there is too much competition. Faced with so much pressure, a good part of the audience has withdrawn, does not risk publishing and prefers to play a passive role. Ergo, posts always come from the same people, who always post the same thing.

It is beginning to be difficult to distinguish lies from truth. The proliferation of cheap content generated by artificial intelligence has started to sow seeds of doubt in us. Deepfakes have made us believe things that weren’t said were said, just as AI-generated images have convinced us of things that never happened, such as that Donald Trump had been arrested in front of the Capitol in Washington. Increasingly, you have to be more alert and sharpen your senses.

Everything is inbred and self-referential. It is unlikely that we will discover a new website, an original newsletter or an interesting author if we let ourselves be carried away by the algorithm and do not regain control and decide to only go to the sites that we are really interested in. One of the great values of the first generation of blogs was that they linked to other universes and opened unknown doors. Nobody insisted that the user stay on their blog. But that’s a thing of the past. The big technology companies have no interest in taking you to a site other than theirs, they will link to their own content, and they will have you wandering around like a zombie within their four walls. The most recent example was seen by Elon Musk on X (former Twitter), which now hides news links and headlines so that users stay on the platform.

Good things are starting to be scarce and expensive (or at least behind a paywall). Two signs are becoming unmistakable in distinguishing the wheat from the chaff on the Internet: subscription and scarcity. Any serious prescriber, well aware of its value, no longer gives away its assets or trades them for visibility; instead, it creates a newsletter, charges for the content and waits for people to come looking for it. It is the silent luxury. Surfing the internet today also means literally running up against the paywall of major newspapers, which only open their doors in the face of wars and catastrophes. The world will be divided between those who decide what they read (and pay) and those who let themselves be led (for free) by the algorithm.

They have turned us into content machines (and really, who wants to be that?). It doesn’t matter what you do: poetry, movies, cooking recipes, cat photos, selfies, memes or insubstantial comments, everything is content. And what is content? According to Kate Eichhorn, a new media historian and professor at The New School, it is digital material that “may circulate solely for the purpose of circulating.” In her recent book Content, Eichhorn points out that content is bland by design because it has to be that way to travel light in digital spaces. “Content is part of a single and indistinguishable flow,” she writes. Intellect, time and vanity diluted in an insipid stream of digital material destined to circulate until it is exhausted. And we still wonder why we get bored on the internet.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.