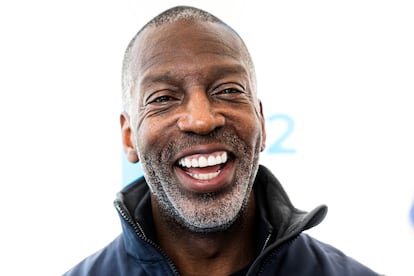

Michael Johnson: ‘I would love to say that I invented my running style, but I didn’t. It was just natural’

EL PAÍS spoke with the four-time Olympic champion and former 200m and 400m world record holder, who suffered a stroke and today works for inclusion in sports

Michael Johnson ran with gold shoes and very short steps at a time when athletes were the only kings of the stadium, and his charisma transcended the limits of his sport. He is the only one in history who has won the gold in the 200m and 400m in the same Olympics (Atlanta 96) and the only one who has been proclaimed Olympic champion of the 400m, the distance of the gods, in two consecutive events (Atlanta and Sydney 2000). He is a physical wonder who found out — and everyone else along with him — that even the strongest human being is always fragile, when he suffered a stroke, a cerebral hemorrhage, in 2018. He recently visited Madrid, Spain, to participate in the sports days held by the Sanitas Foundation.

He cheers and applauds, but due to medical advice he cannot take part in the relay where Spanish champions — María Pérez, Álvaro Martín, Aauri Bokesa, Óscar Husillos, Mariano García, Mo Katir, Adrián Ben and more — compete with athletes with disabilities. “I think what Sanitas is doing is really remarkable, including people who may otherwise be separate from everyone else. I think this is very important. You know, the more we can include people and see everyone as humans regardless of the differences that we may have, whether that be physical differences, or whether that is race, or whether it’s gender, or nationality, or religion or whatever, the better we will be,” says Johnson, who lives in London, where he is a commentator for the BBC, and who barely shows the effects of the stroke, except for a certain stiffness in his walk and in one arm. “We find so many different reasons to be separating people. I think it’s very admirable to include people so that we just see each one as humans.”

Question. Everybody thinks that great athletes are supermen, but your stroke reminds us that they are as fragile as everyone else.

Answer. Exactly. I think I’m a good example; a bad example, but also a good example of that. Yeah, anyone can have a health issue, so it’s very important to take really good care of yourself. I was already taking very good care of myself, so it’s strange that I had this stroke, but the benefit was that I was able to make a full, very quick recovery, because I was already in very good shape and I had already taken very good care of myself and my health prior to my having the stroke.

Q. Did your discipline as an athlete, your capacity for suffering, and resistance to pain help you recover better?

A. Absolutely. The recovery from stroke recovery is very, very difficult for most people. I had to learn how to walk again, how to stand, and it’s a very difficult process. But I’m certain that because of the training and the experience that I had as an athlete, having the mindset to be able to deal with the setbacks, being able to deal with the training and the difficulty of the training allowed me to make a much quicker recovery.

Q. Perhaps your first major setback took place in Spain, when you got food poisoning after eating in a seafood restaurant in Salamanca, which hindered your participation in the Barcelona 92 Olympics, where you were the favorite for the 200m... you were 24 at the time.

A. Yes, that was the biggest disappointment of my life. As an Olympic athlete you know that once you get to the Olympics, it’s very difficult to get back. Obviously, I got back two more times, but you don’t know that at the time. And, you know, especially as a sprinter in America, it’s very difficult just making the team. It becomes more difficult to make it on the team than the Olympics. So it was very disappointing for that reason, but I think it was something that helped me with my drive going forward. I think I learned from that one how to deal with other setbacks and disappointments.

Q. Seven years later, in 1999, your next visit to Spain was more glorious. You won the World Championships in Seville and broke the world record for the 400m (43.18s) on a night of tropical heat and popular acclaim.

A. It is one of the best memories of my career. I had been chasing this record for years, and finally was able to accomplish it. The conditions were perfect. I was in the best shape. So, yeah, I have great, great, great, absolute amazing memories of that. Definitely, one of the most memorable moments in my life.

Q. Your record lasted 17 years, and when South African Wayde van Niekerk broke it (43.05 in Rio 2016), everyone thought that the 43s barrier was about to fall... If he had not broken his knee playing rugby, do you think he would have succeeded?

A. It’s very difficult to say. I think he had the potential, but I felt like I did as well. But it’s just very difficult. The 400 meters, it’s a very long sprint, so there are a lot of opportunities to make mistakes. That’s one of the things that makes it really, really difficult. And it’s very tough physically as well. It’s very unfortunate for him because I know that that was one of his goals, to run under 43 seconds. And he was fortunate to break the world record when he was still very young [24 years old]. I was already at the end of my career, so I was like, “I’m not going to keep going.” I wanted to break 43, but at that point I was already in my 30s. And it’s very difficult to stay healthy and train hard and keep your body healthy. It was time for me to just move. But for him, it’s really unfortunate. Now I think it’s too late.

Q. Is it something you regret, not having been the first and only one to go below 43s?

A. No, because 42 seconds was not a goal for me. Breaking the world record was a goal for me. I do believe I could have run 42 seconds, but it wasn’t a goal. If I had broken the world record in the 400 meters earlier in my career, then I would have certainly gone for 42. But I already knew in 1999 that after 2000, I was going to retire. So, yeah, no regrets at all.

Q. You ran with gold Nikes. Now everyone runs with magic shoes made of carbon plates and light foams and the records in all distances are falling, except for the 400m. In the last World Championships no one went under 44s.

A. I think it’s hard to say, you know, what effect the shoes have. Certainly, the shoes, whether they are for marathon or for sprints, are helping some athletes. But there’s more than just the shoes when it comes to breaking records. There are the athletes themselves, and how fast they’re capable of running. The shoes are going to help them, but they’re only going to help them so much, and some athletes more than others. And then when it comes to actually breaking records, yeah, it’s more than just the shoes. It’s also the conditions. It’s also, you know, how much talent is in that event at the current time. Right now is not the best time for men’s 400. And of course, in track and field, sometimes one event is up and another event is down. Then 10 years later, it is the exact opposite.

Q. The 400m is the perfect metaphor for pain and ecstasy. An athlete thinks they are dying when their lactic acid rises in the last stretch and ends up dizzy and vomiting, but then they feel like a god. Do you see it that way? Is that part of the greatness of the test?

A. No, I think different 400-meter runners handle it differently. I think Van Niekerk is unique in that he has a very difficult time at the end of the race, versus other athletes who maybe don’t. I was a 200 meter sprinter moving up to the 400. You would think I would have had a more difficult time, but I didn’t have a very difficult time with it. I think it’s different for every athlete. Sometimes it’s in how you train. Training for me was harder than races. Training was very, very hard for me. And most of my training partners were pure 400-meter runners, as opposed to me being a 200 moving up to the 400. So I had good training partners, but I was rarely winning in training. I was always losing in training. In the race I can win, but the training was harder for me.

Q. You ran differently than everyone else, upright like a duck, rigid like a statue and with very short steps.

A. It’s just the normal way that I always ran. I would love to be able to say that I invented it, but I didn’t. It was just natural.

Q. How would you define your style?

A. There are two ways to look at a running style. One is biomechanically and efficiently, you know, how you’re running in terms of how much speed and power you can generate. The other way to look at it is just visually; how does it look?

Does it look beautiful? Does it not? The second one doesn’t matter so much. It’s the first one that matters. People always say, “Oh, I love the way you run, it’s so beautiful.” Thank you. But more importantly, is it efficient? And that was the thing that we found early on, that power is a very important component of sprinting, the amount of force and power that you can put into the ground. I was very fortunate that the way that I ran allowed me to create more force, which creates speed.

Q. In the 21st century, with the exception of Usain Bolt, athletics stars are no longer global stars that break the boundaries of their sport...

A. There’s no doubt that athletics is not at the same level of importance in the world of sports as it was 30 years ago, which is very unfortunate. It has fallen quite far in terms of global sports and how they rank with television viewership and attendance. This is a shame. I would like to see a change. I’m hoping that it can change, because the athletes are more amazing now than they were when I was competing.

Q. When Bubka was the best, he was a myth for everyone. Now Mondo Duplantis jumps higher but only the biggest fans admire him.

A. Exactly. And that’s a shame. I think the athletes are very frustrated, even more so than the previous generation. In the generation after mine, I think most of the athletes just sort of accepted that they’re not a top-tier sport anymore. This generation today, the Noah Lyles and Mondo DePlantis and all of these athletes today, I think that they are very, very frustrated, because they expect more, and they should expect more from their sport.

Q. Is this the price that track and field pays for so much doping in recent decades?

A. Obviously doping has been really difficult for track and field. But track and field is not the only sport with a doping problem, and other sports have continued to be able to thrive, so I don’t think that you can attribute it to doping. Think about cycling. Cycling had a huge doping problem. It continues to thrive. In our country, baseball had a really big doping scandal in the early 2000s, but the sport has continued to grow. Television contracts, athlete contracts continue to grow. I’m not going to minimize the problem that doping has caused in athletics, but I don’t think that you can blame the downfall of the sport and the fact that it hasn’t recovered — and it continues to go down — on doping.

Q. Any ideas to change the trend?

A. The sport has to change and be reimagined for today’s sports and media and entertainment world. Sport is entertainment. The media is a big driver of sport values and their entertainment value. If you look at athletics as a sport over the last several decades, even since before my time, the sport hasn’t really changed its format very much. There are little changes here and there, and those aren’t enough, obviously. Somebody’s going to be disappointed, but those are the things that leaders have to do in order to save the sport. Trying to satisfy everyone makes you stagnant. The only way to keep everyone satisfied is to not change anything. And that’s not a solution. Changes have to be made.

Q. Is Sebastian Coe, president of World Athletics, the international federation, the leader that track and field needs?

A. This may not be their job for the federations. Maybe it’s for someone from outside. Because federations like World Athletics are very good, and they have done an amazing job, with governance and staying on top of the doping issues. Rules and regulations; that’s the job of a federation. But in order to create a professional league for a sport, that’s typically not something that a federation or governing body can do very well.

Q. I read that you have played flag football, the light version of American football, which is going to be an Olympic sport in Los Angeles 28. What do you think of that?

A. I think it’s good. I invested years ago into a flag football league because we saw the future and saw that the NFL is the most profitable and highest value sports league in the world, but also a very dangerous sport. Flag football is football still, but not as dangerous. Even the NFL is embracing flag football. It’s been a little bit behind other sports, like, say, the NBA, but they’re starting now to expand globally. I think that American football, NFL style football, is becoming much more popular around the world, and I think that flag football in the Olympics will be fantastic.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.