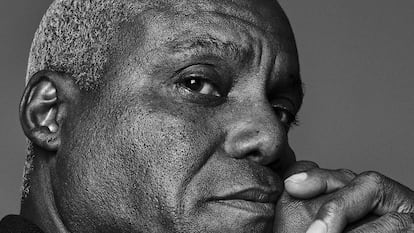

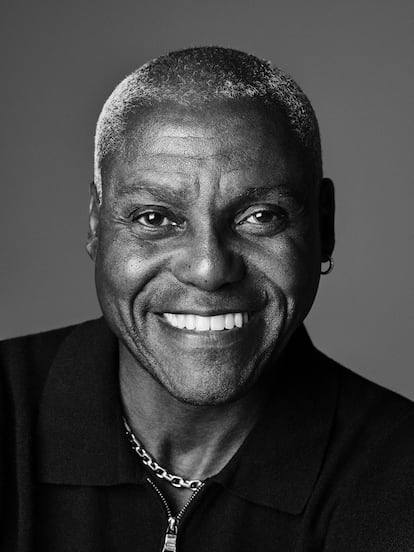

Carl Lewis: ‘There is a perfect way to run. One perfect way’

The ‘Son of the Wind’ failed as an actor, singer, and politician. But with nine Olympic golds and ten World Championship medals under his belt, ‘King Carl’ remains one of the greatest athletes in history

Carl Lewis lands in Madrid a day late, which has allowed him to discover “the worst airport in the world” in Frankfurt and reach two conclusions: “Flights are delayed from time to time. And you never have to fly through Frankfurt.” He seems like the usual Carl Lewis: the athlete whom those who did not buy him - managers, executives, federation members - described as intransigent, arrogant and conceited, while denying him and other athletes the right to personality, rebellion, authority, ambition, discourse, taste for fashion or simply to be able to cut their hair à la Grace Jones, with parietal gradient avant la mode. Lewis, who is considered by many to be the greatest athlete of the 20th century, has had to carry that fame throughout his career, a level in the sports mythology of the United States perhaps only surpassed by Michael Jordan or Muhammad Ali.

Now 61, after a track and field career that reaped nine Olympic golds and 10 medals at world championships, he still distributes doctrine. But today, in Madrid, Carl Lewis is not an arrogant being - he is more of a man with white hair cut to the millimeter who is annoyed by imperfection and a bit of a curmudgeon. He failed as a singer, as an actor and as a politician. He was never as popular as his successes might have made out and he accepts that as a consequence of his permanent fight to make athletics move toward professionalism, so that athletes could make a good living from their work. And he continues to train young people at the Santa Monica Club in Houston.

Question: What would you have been like, what would your life have been like, if you hadn’t become the Son of the Wind?

Answer: That is impossible to answer. I work with young people and when I tell them about my life I explain that my only aspiration was to be a professional athlete and jump 8.90 meters. It was the reason why I became what I was. When I started in athletics, nobody earned enough to live off it and I decided to change it, fight for professionalism. That’s why I wanted to become famous, so that people would listen to me. To get that influence, the next step was to become the biggest star in the sport, and I did that with four gold medals. I didn’t know where it would go, but I always ask young people: ‘What do you want to be? What goal do you want to achieve?’ That has been my life, exploiting my talent. And I don’t know what I would have been without it.

Q: Do you visit Madrid very often?

A: I don’t know how many times I have visited Madrid, five or six since the 1980s and 1990s, I think. I have traveled so much that it is difficult to remember. I’ve been here with Nike, a company I still get paid from. Since 1997, after I retired, I have continued to move around quite a bit on business.

Q: On this occasion, together with the Spanish Paralympic champion Teresa Perales, you have traveled here to support the work of the Sanitas Foundation in favor of inclusive sport...

A: It could be said that I have been involved in the fight for inclusive sport since I was little. I got into track and field because my mom founded a track and field club for girls, since none existed in the area where we lived. So my whole career was based on inclusion, on equality. And of course, coming from the southern United States, in Birmingham, Alabama, the civil rights movement was always very present. All of these issues have been important and have been a part of my entire life.

Q: You are an athlete, Black, a reference figure... Do you feel committed to continue fighting?

A: There has always been a racist undertone in America. When Barack Obama became president of the country in 2009, the vision of a family of color that could be accepted by the world triggered fear. Racism returned. It was called Tea Party. In the same way that Obama gave people of color a voice and delivered the message that we have a chance to get things done, Trump gave racism a voice to say: “It’s okay to be racist, it’s okay to be hateful.” The fight for civil rights will never end as long as there are those who fear what will happen if they lose power.

Q: In 2011, you tried to run for the Senate in New Jersey for the Democratic Party. However, the candidacy was annulled because it was considered that you did not meet the requirement of residence in that State. Was it the end of your political career?

A: Yes. I ran in New Jersey after living there for a short time because I saw a clear hole in the system. There wasn’t a voice quite like mine. And that’s why I applied. However, Houston, where I grew up, became an athlete, and spent my entire sports career, is the complete opposite. That’s why I came back. I’m too liberal for southern New Jersey, I assure you. The values there did not agree with mine.

Q: More than for the magnificence of your records and times, you are remembered for your style, always said to be athletic perfection…

A: I was looking for perfection. I was trained by a coach, Tom Tellez, who understood that you had to try to be perfect. And between the two of us we looked for the perfect stride, the perfect jump, the perfect position. And it didn’t scare me. Many times we limit ourselves because we fear that we will never reach our goals. I never wanted to have to say to myself, “I wish I had tried.” I wanted to jump far, run fast, be rich. And I wanted it at 17 years old. And I found a person, Tellez, who told me: ‘I’m not afraid to help you try. You have to do it.’ I knew I had to be the very best athlete that could exist and achieving perfection was my goal in every single race.

Q: Is there perfection?

A: There is only one perfect way to run, only one. And the closer you get to it, the easier it seems. It’s hard to describe. It’s a rhythm. It’s all about setting a rhythm and sticking to it. It is a contradiction: the sprint is pure acceleration and also absolute relaxation. When I ran best [his mark of 9.86 seconds in the 100 meters was a world record for several years] was when I was most relaxed. That was when it was easier. The first thing an athlete has to learn is that the better they do, the easier it will seem. The best runs are the easiest because suddenly everything works perfectly, every single aspect of the body.

Q: And what did you feel running perfectly in the finals of Rome 1987 and Seoul 1988, and watching Ben Johnson, who was later banned for doping, beat you twice with the world record right under your nose?

A: All the athletes, all the federations, the whole world, we all knew that Ben Johnson was doping. Doped athletes are bad for business. Even if their punishment comes later, they will have harmed the sport. Ben was that, because he was using drugs. It didn’t hurt me personally, but because it affected the business, the sponsors were moving away from our sport. We had worked hard to make track and field a professional sport, and Ben Johnson comes along…

Q: Before being a sprinter, you were a long jumper in high school and you won gold medals in four consecutive Olympic Games, which no one had ever done... But you never broke the world record. Mike Powell eventually did, with a jump of 8.95 meters at the World Championships in Tokyo in 1991.

A: I respect Mike Powell because we were competing against each other for 10 years until he beat me. Ten years! And he had the physical and mental ability to go out there and jump enough to break the record. Others of us tried, but no one else succeeded. The long jump has always been that way, one person challenging everyone else.

Q: No one doubted that destiny had chosen you to reach nine meters…

A: I always thought I could beat him at any time, that 30 feet [9.14 meters] would come without thinking about it, just like that, whoosh, but really there was another matter. If he had only been a sprinter, he would have run the 100m in 9.70 seconds [Powell’s best was 9.86s]; If I had only been a long jumper, I would have made it to 30 feet, but I was both, and one compromised the other. The important thing was not breaking the record for long jump, but the development of athletics as a professional sport. I had so many things on my mind that I knew I would always have to sacrifice something.

Q: In Tokyo you made the best four jumps of your life, jumps that no other athlete, except Bob Beamon [who broke the world record with 8.90m in Mexico in 1968], had ever made: 8.83m, 8.91m (with wind), 8.87m, 8.84m, and, even so, your rival jumped 8.95 and took the world record... Wasn’t that frustrating?

A: Tokyo was the only time in all those years when I said to myself: “Today is the day the long jump record goes.” And it just so happened that for Mike Powell it was also the day. I knew that with so many sprint races I was sacrificing length, and every year I had put the record out of my mind because I had so many things to do. And I get to Tokyo and I change and I say to myself: “Today I can do it, today I’m going to do it.” It was like when someone gets married and says: ‘Great, we’re going to travel, we’re going to go around the world.’ But then you’ve got three kids and you don’t go around the world. It’s not because you’ve given up on the idea, it’s because you have to raise your children...

Q: The next great sprint figure, the next big athletics star, was Usain Bolt, who holds the world records for the 100m [9.58s] and the 200m [19.19s]. Have you ever spoken to him?

A: No never…

Q: Would you have beaten him?

A: Athletes compete in the present, not against the past or the future. Someone recently lectured me that things have changed, that young people run faster than when I ran, so they’re better… Well, I ran faster than Jesse Owens, didn’t I? But that is not the issue.

Q: Going under 10 seconds in the 100m seems like child’s play today, and Johnson’s 9.79 seconds has been widely surpassed, but there is less talk of doping than of technological revolution, of magic shoes... Are they a danger to the credibility of athletics? Do they rob it of its artistic side?

A: Shoes are the most important thing to happen to athletics in the last 30 years. Science is science. Shoes have a big impact. In the 100 meters, for example, between 44 and 50 steps are taken. My stride was just over two meters. If I add an inch, three centimeters, to my stride, it seems like nothing, right?, but then suddenly a mark of 10.01 seconds becomes 9.95 seconds… That’s what the new shoes do. I love them, and I always oppose those who criticize them. Evolution is like that. It’s the future. Athletes compete in the present, not against the past. You can’t compete in the future, so you can’t worry about the past. And that’s down to the shoes.

Q: However, you did compete against the past in a way, at Los Angeles 1984, your first Games, the myth of Jesse Owens, the Black athlete who won four gold medals in Berlin in 1936 with Hitler sitting in the stadium... 100 meters, 200 meters, long jump, the 4x100m relay, the four golds you won.

A: Ha ha ha, yes, maybe that’s a nice way to put it, but it wasn’t like that, I wasn’t competing against the past, against Jesse Owens. If anything, I was using material from the past to build my future: it wasn’t about Jesse Owens, it was about the four gold medals. That was it. Competing now. As there will always be records to break, there will always be a connection to the past, but I was competing with the other athletes who were there, at that moment, on the track. Winning four golds, the same golds, gave me an incredible connection with Jesse Owens, and that was the final detail that made me a global superstar. That’s why I had to go for all four, it was part of my publicity package.

Q: What do you think Bolt thinks of his career?

A: Everyone knows my world is different, it’s another world. For these kids, the world before the year 2000 does not exist, and it’s a pity because, if they were able to extend their vision of time back 30 years ago, they would see the serious problems the sport is going through now. But no, they close themselves off to everything around them and make life revolve only around them.

Q: But you don’t want to talk about Bolt…

A: The problem is that whenever I say something about Bolt, people take it personally, as a criticism of the person. It’s like when you talk about Donald Trump. If I say, “Your policy is wrong,” he replies, “You are ugly.” It’s the Trumpification of the world. You talk about ideas, about policies, and they criticize the person who criticizes them. The fact is that I and others have given so much to make the sport a better place for everyone, I have sacrificed so many things... If it hadn’t been like that, I would have earned more money, for sure. But, if I say that, there is always a percentage of the athletic world that responds: “Oh, my God, this attitude…, blah, blah, blah.” Look, athletics improved economically and globally thanks to three figures: Jesse Owens, Tommie Smith and John Carlos [the American athletes who raised their gloved fists representing Black Power on the podium at the 1968 Mexico Olympics] and me. And at some point in our careers we were all called assholes. John Carlos and Tommie Smith were stupid, I was stupid… That’s how it was. It’s not a coincidence. Billie Jean King was an asshole… All of us who made an impact on sport were called stupid, but we were leaders willing to sacrifice for others to improve. So I’m not interested in anyone telling me I’m wonderful. It’s not about that, it’s not about me, it’s not about my celebrity. It’s about the impact you’ve had, what you’ve left behind you. The question is: is the world better after you have been through it?

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.