Obama: “Significant damage has been done in the US and around the world by Trump”

In a conversation with the editor-in-chief of EL PAÍS, the former president reflects on the current moment and the pandemic, Donald Trump’s four years in power, the polarization in his country and also the future with Joe Biden in charge of the United States. His conclusion is optimistic – a cautious optimism

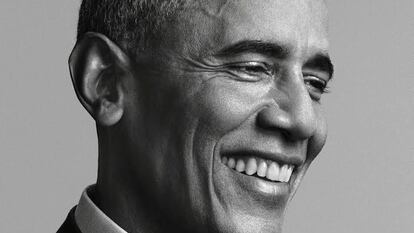

Obama

“Significant damage has been done in the US and around the world by Trump”

Watch the interview Go Photo: ©Greg Kahn

Photo: ©Greg Kahn

The United States is living through strange times. The protocols for the orderly transition of power, as revered as the American Republic itself, are currently in danger due to the refusal of the current occupant of the White House to accept his defeat. The process is a secular rite, a democratic liturgy during which the loser not only recognizes they lost, but also, by accepting the victory of their rival, bestows upon the latter the legitimacy to pursue, like in a relay race, the search for that “more perfect union” prescribed by the Constitution. It is also a message to all citizens, in particular those who were on the losing side, that it is time to heal wounds. In the book that he has just published, A Promised Land, former US President Barack Obama recalls the impression made on him by the gracious way that George W. Bush and his family carried out that duty. “I promised myself,” he writes, “that when the time came I would treat my successor in the same way.” His successor was Donald Trump. During the conversation that we had last Sunday in Washington, I asked him if he did in fact do so, with grace.

— I did.

— Was it tough?

— It was tough, but I did it. [Obama cannot avoid a smile of complicit acknowledgement at this moment]. I called Donald Trump that very night, late at night, to congratulate him, even though his victory over Hillary Clinton was about the same margin as Joe Biden’s victory over him. I made that call, we didn’t delay for weeks on end pretending that it hadn’t happened. I invited him a few days later to come to the White House with his wife, Melania. I arranged for all of my agencies and teams to prepare manuals for the transition. Apparently, they weren’t always read. One of those manuals was a playbook on how to deal with the possibility of a pandemic. It seems that they didn’t follow those guidelines that we provided. So I actually felt that I had tried to pass on the same lesson that I had learned from George W. Bush when I came in, and that the peaceful transfer of power between parties is part of what makes a democracy work.

— Which leads us to what’s happening now. Not only has President Trump not invited President-elect Biden yet, he has also not conceded. Did you ever imagine this was even possible in your country?

— I wouldn’t have imagined it four years ago. I am sad to say that by the end of Donald Trump’s presidency, I was not surprised that he is acting the way he is acting. Michelle and I talk all the time, and I think it’s reflected in the book that I tend to be a little more optimistic. Michelle tends to be a little more pessimistic about human nature and how much things change and how much things stay the same. And so we’ve been having these conversations over the last four years and certainly over the last four weeks. I try to remind Michelle that when I was born, in much of America, likely in this hotel, there were probably no African American guests. If you and I were meeting, it would be because I was carrying your bags. That’s in my lifetime. And we’re now sitting here, and I’m the former president of the United States. And as frustrating and sometimes discouraging as the news can sometimes be, 59 years in the course of human history – that’s a blink of an eye. The progress that this represents, we’ve seen in other places. When I was born, Spain wasn’t a democracy and Europe was still rebuilding out of a war that had killed 60 million people.

1. A divided country

The hotel in which we are sitting, the Fairmont, is located in Georgetown, a neighborhood in the federal capital that is home to the university of the same name. On Saturday morning, the weather was sunny and mild, exceptionally clement conditions for mid-November. Students packed the sidewalk cafés and restaurants, in streets lined with exposed-brick houses, in an atmosphere of serene calm. A few miles away, however, there was a clamor. Thousands of Trump supporters, who had come from all over the country (in Washington, 90% of voters backed Biden), occupied the enormous public space between the White House and the Capitol, with signs that denounced a fraud that only exists in their heads, and with slogans that also, in passing, foresaw the apocalypse. Vanquished by the sun, an older gentleman was sitting on the sidewalk holding up a poster that stated: “If Biden gets to the White House it will be the end of the USA.”

On polarization: “America is deeply divided.”

All of that agitation started four years ago; or perhaps even earlier. After leaving the White House, Obama took his last flight on Air Force One, accompanied by his wife. “Headed West,” he writes in his book, without going into more detail. The tome is more than 700 pages long, and is the first of two. In it, he recounts his unlikely journey from an obscure legislator in Illinois to the United States Senate; and from there, almost without interruption, to become the Democratic Party’s candidate for the presidency, a ray of hope for millions of Americans; and finally, after an explosion of joy not seen in decades, to the Oval Office. That day, on board the presidential aircraft, however, his mood was left bittersweet “by the unexpected results of an election,” he writes, “in which someone diametrically opposed to everything we stood for had been chosen as my successor.” What followed did not improve things. So I asked him about his state of mind over these last four years.

— There is no doubt that some significant damage has been done both here in the United States and around the world. If you ignore science, if you ignore facts, then a pandemic is going to be worse. If you encourage, or at least are forgiving of, racist behavior, then those who have those impulses feel emboldened. If you embrace dictators on the world stage, then the commitment to democracy diminishes. During the last four years, there’s no doubt that there have been times where I felt frustrated, in part because I came into office in 2008-2009, when America was also going through a crisis. We had a global financial crisis. We had the war in Iraq [which began under his predecessor, Bush], which had divided this country and alienated many of our allies. And for eight years, we worked very hard to restore America’s standing in the world, to rebuild the economy. By the time I left office, America was in a strong place, and to see some of that progress dissipated unnecessarily, is… Yeah, there’s no doubt there’s a sense of frustration there sometimes.

On Trump: “If you ignore science, if you ignore facts, then the pandemic is going to be worse”

— And now with the election of Biden?

— Well, I think what we saw in this election is that America is deeply divided. And some of those divisions preceded Donald Trump. Some of them will still be here after Donald Trump. But what is certainly the case is he accelerated those divisions. He fanned the flames of division. And I know that Joe Biden is somebody who, by instinct and by character, is a unifier. And I am confident that one thing I learned as president is it matters what the president says, it matters the tone that the president sets. The president of the United States can’t solve every problem, even though oftentimes people expect that he should be able to do so. But he can encourage a certain way of interacting, civility, a sense of understanding of others. I think he can set a tone internationally in terms of how we interact with our allies, how we approach diplomacy. And I think that you’ll see in Joe Biden a return to some of the traditions that I tried to uphold when I was president.

— You write in the book that citizens saw what was best for you, “a voice insisting that for all our differences we will remain bound as one people, and that together men and women of goodwill could find a way to a better future.” Later came the attacks you suffered during eight years in the White House, then Trump’s presidency. And even if Joe Biden is now the president-elect, we can see how divided the country is and how outraged a part of it is. We saw that yesterday on the streets of Washington. Do you still sustain this optimistic view today?

— I do. It’s always been a cautious optimism in the sense that history doesn’t just move forward. It moves backwards. It moves sideways. There is no doubt that humanity has made progress over the last 2,000 years. It’s less violent, it’s better educated, it’s healthier, and yet we still have war and we still have cruelty. We still have places where people have no rights. We see it every day. And the same is true in America. America is a better place than it was two hundred years ago. But there’s still racism. There’s still inequality. As president, I made a habit of having town hall meetings with young people. What always struck me was the degree to which they believe, much more than their parents or their grandparents, that all people are equal, that people should be judged on their character and not on the color of their skin or their religious background or whether they’re men or women or their sexual orientation. They embrace the idea of a common humanity. But the challenge is that you still have older voters who resist these changes and you also have a legacy of institutions that are, if not broken, then in disrepair. And so our government, the democracy of the United States, has issues that makes it hard for it to respond quickly. And if the parties are polarized, that means you get government gridlock. People get cynical, they get discouraged. So I recognize that the path forward will be difficult. We can’t take it for granted that democracy is always going to work because democracy is the most difficult form of government, because it requires each of us as citizens to constantly be paying attention and to hold our leaders accountable, and to analyze critically what’s being said and what’s true and what’s not. And that is more difficult in this modern age than ever.

On the future: “What makes me optimistic is the younger generation”

2. Early warnings

That is, indeed, more difficult now than before. The division in US society that Obama is talking about has been around for a long time, but undoubtedly in recent years it has been exacerbated to troubling levels. By the time Trump arrived, the stage was set and the machinery well oiled. It’s interesting to hear how Obama describes the phenomenon of Sarah Palin, John McCain’s Republican running mate in the 2008 elections. Palin became a laughing stock among liberal elites on both coasts due to her ignorance, the self-confidence with which she managed that ignorance, and her disdain for a way of doing politics that was, until then, unthinkable. Obama sensed – and feared – something else.

Whether it was because he perceived that moment with clarity or because, in retrospect, he has had an enlightenment, Obama writes that “Palin didn’t care if the editorial board of The New York Times or listeners of National Public Radio questioned her abilities. She offered these criticisms as proof of her authenticity, because she had understood (long before her detractors) that the old gatekeepers were losing relevance and that Fox News, talk radio and the building power of social media could provide her with all the platform she needed to reach her intended audience.” He is, I tell the president, describing the harbinger of Donald Trump, eight years before he appeared on the stage. But it seems as if nobody paid attention. When did you become aware of those risks, I ask him, and what could have been done differently?

If you want to support the creation of articles like this one, subscribe to EL PAÍS.

Suscribe here—America has always had a warring narrative, a contest of ideas between our founding documents, that declare all men are created equal and believe in rule of law and freedom of speech and all these wonderful principles, and the realities of slavery and the decimation of Native American tribes and discrimination against various groups. And so on one side is the narrative that says, let’s live up to those ideals. Let’s include more people. Let’s reduce the influence of race. Let’s lift up people without property and workers and give them a chance. And then there have been those who said no, we want to preserve privileges and status for a certain group of Americans and not others. And there have been times in our history, and I think my election was an example of when that narrative of inclusion was ascendant, and then there have been other times where there’s been pushback against these changes. And Sarah Palin, I think, was an early sign that there was pushback against what my election represented and the coalition of people who had elected me represented. And the challenge that I saw even then and throughout my presidency was the degree to which the media, I think, was willing to entertain the notion that Sarah Palin or the Republican Party, that their criticisms or obstruction or resistance to my policies were somehow based on anything other than a desire to go back to the days when people like me weren’t in the Oval Office. We now have a multitude of media, so that many Republican voters don’t hear anything to contradict what Donald Trump says. There are alternative facts and an alternative reality that we’re seeing even now, when Donald Trump declares that “I haven’t lost the election yet,” or “there’s been fraud and illegal votes cast,” even though there’s no proof of it. As a journalist, I’m sure you have a sense of this as not just an American phenomenon, but a global phenomenon, particularly because of social media and the internet. And so one of our big challenges in all our democracies is: how do we go back to the point where we can have a common baseline of facts? Because the idea is we should be able to debate ideas. We should be able to debate solutions to problems. But we should be able to agree that climate change is real. We should be able to agree on economic statistics. We should be able to agree when the votes are counted at the end of the election, who’s won and who’s lost. And that, I think, is what you saw in Sarah Palin. It continued throughout my presidency and in some ways has gotten worse over the last four years since I left office..

—There are many interesting insights about politics and technology in your book. In one passage, you say: “What I couldn’t fully appreciate yet was how malleable this technology would prove to be, and how one day many of the same tools that had put me in the White House would be deployed in opposition to everything I stood for.” When did you become aware of those risks? Is there anything you wish you had done or said during your presidency to avoid social media tearing apart the fabric of modern societies the way they happen to be?

—Keep in mind that this is an indication of how fast everything is moving. The iPhone doesn’t even get to the market until 2010. I mean, that was 10 years ago. And so initially, I think we all felt, this is going to be all for the good and, you know, I think where you start seeing a recognition that there is a dark side to this is that during the Arab Spring, you see people who are advocating for democracy in Tahrir Square using Facebook and Twitter to organize young people to protest against repression by the Mubarak regime. But it’s only a few years later that you see ISIS using it to mobilize terrorists. And what you become aware of is that the same kind of activity that can help educate children in a remote village in Africa because they now have access to the world’s library on a phone is also the same tool that can be used in Myanmar to try to engage in ethnic cleansing and oppression against the Rohingya. And what that means is, I think, that all of us are going to have to find the ways of balancing and capturing the good of social media and reducing the bad. Doing that in liberal democracies is more difficult, because we have traditions of freedom of expression. I think the question then is: is there a combination of regulation and corporate practices that can help to reduce some of the damage that we’re seeing? I think one of the things that we’ve learned during the Trump presidency is that a lot of the things that hold a society together aren’t written down in a code. They’re not subject to criminal sanction, they’re expectations and they’re values that are transmitted and traditions that we have to rebuild, and we have to teach to our children. One of the things that Michelle and I talk a lot about is how do we create an education system that allows our children to think critically and understand that there are objective truths out there. That the Enlightenment values of logic and reason and facts and objectivity, and confirmation of hypotheses, all these things that help to build modern life. I think you and I grew up assuming that everybody would come to embrace those. What we’ve discovered is that we have to reinforce those traditions all the time because the older spirits of the Dark Ages are always ready to come back and reassert themselves.

On technology: “We need to capture the good of social media”

3. The legacy

In her review of A Promised Land for The New York Times, the prominent Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie coins a phrase that sums up the propensity of Obama – something that he himself recognizes in his book – to think about things over and over again, to ponder the ponderable and the imponderable, only to end up not taking a firm stance: “Doing an Obama.” Both in his writing and in his presidency. For many progressives, the fact that Obama would “do an Obama” on issues about which they wanted and expected to hear resounding declarations such as racism, inequality or foreign and military policy (the president kept Robert Gates, Bush’s defense secretary, in the role) was a huge disappointment.

You ran for the presidency, I say to Obama, with the idea of change. Of significant change. But time and again, in your book, you justify why that change could not go beyond what you proposed, accepted or legislated, with healthcare reforms as well as other issues. Do you still believe that you pushed as hard as possible? I ask him. That the United States could not have handled more change than what you delivered? Are there any second thoughts about that?

—You know, I always have second thoughts. Because by nature, after you’re finished, you say, oh, man, I wish I could have gotten more done. Take the healthcare law that we passed. Twenty-three million people have health insurance who didn’t have it before. But there’s still several million people in America who don’t have health insurance. And so I would have preferred to have everybody get health insurance. At the end of the day, I was constrained by the number of votes that I had available to me, and one of the things about politics – at least in a democracy – that you’re reminded of, is that no matter what your aspirations are, no matter how bold your proposals are, sooner or later it becomes a math game. Do you have the votes to pass this? What I realized as I was writing the book is that my proposals were actually as bold as I would have wanted, and I just kept on pushing until at a certain point I had to make a decision: am I going to take this half loaf or no loaf? And I ended up developing a saying inside the White House with my staff when we’d be arguing about how much to compromise. At some point you’d say, is this going to be better than what we have right now? And if somebody said, “Yes, it’s better.” Then I’d say, you know what? Better is good. You can’t make the ideal the enemy of the good. I think that if I were to do it all over again, obviously there are probably some messaging mistakes that I made that I wouldn’t repeat – how I described our goals, how I tried to market our ideas. I probably would refine and have a better sense of what dangers were out there that I had to be careful about…

—You never expected the backlash that came afterwards…

—I always expected backlash. We came in differently than Franklin Delano Roosevelt when he came after Herbert Hoover. The Great Depression had been going on for three years. So everybody knew who was at fault. We had the unfortunate situation of coming in just as things were starting to go down. And so it was harder for people, for voters to be able to distinguish who’s at fault for why things have gotten bad. And the fact that we had stopped the bleeding, and things didn’t get as bad as they did during the Great Depression, in some ways made people feel more justified in asking, “Why are we spending all this money on stimulus programs?” Or, “Why did we have to bail out the banks?” And because things never got so bad that people completely understood why we were taking some of the steps that we did. So I anticipated that all the joy of my election was not going to last forever. I did not expect Donald Trump to be elected. What I did expect, though, was that if he was elected, it’d be one term. I was right about that.

“I always knew there would be a backlash to my presidency”

In that spirit of examining and reexamining everything, including his motives and impulses, hidden sometimes even from himself, Obama describes in his book a revealing scene with his wife Michelle, who had been resisting her husband’s ever-more intense participation in politics. For her, running for president was a red line. Both were in a room with their closest colleagues. She bluntly inquired: “Why you Barack, why do you need to be president?” He became lost in his thoughts. “Barack?” she insisted. Obama mapped out a few lines of defense, thought about it again and said: “There is one thing I have no doubt about. I know that the day I raise my right hand and swear to be the president of the United States, the world will start to see this country in a different way. And I know that all of the children in America (Black, Hispanic, children who don’t fit in) will see themselves in a different way, their horizons will be broadened, their possibilities will increase. Just for that… it’s worth it.”

The room fell silent. Michelle stared at him for a moment, which for him felt like an eternity. And finally she said: “That answer was not bad at all.” Obama could see how the members of his team were imagining the swearing in of the first African American president of the United States.

—Did you accomplish that objective?

—I have never believed that just by virtue of my election, that we would eliminate discrimination in the United States, that Black and brown children wouldn’t still have more barriers to success than some of their white counterparts. But what I did believe was that the sight of somebody who looked like me occupying the highest office in the land, the leader of the free world, would in subtle and sometimes not so subtle ways send a message to those children of what’s possible for them in their lives. And what I do believe, is that when my presidency was finished – and by most accounts it was a successful presidency – that changed how kids thought about themselves and each other, and that was a change not just for Black and brown kids, but for white kids as well, and for girls and for people who think of themselves as outsiders..

While it is only briefly mentioned in the book, Obama told the following story in detail in Washington on Sunday. It’s about a boy who visited the Oval Office with his parents, who worked for the president. When the time came to take a photo, the child said that he had a question. What’s the question, asked the president. The boy, a four- or five-year-old African American child, asked if the president’s curly hair felt like his own.

—And I said, “Well, why don’t you check?” And I bent down and he touched my head and our photographer Pete Souza took a picture. And you can see the little boy touching my head and feeling and saying, “Oh, it does.” And that ended up being, I think, one of the favorite pictures that was ever taken of me in the Oval Office, because it signified this little boy saying, “OK, this very important man – he’s actually like me.” And I think that, in various ways, ends up having a positive impact not just in his life, but in the life of the country.

Obama’s eight years in the White House

See the gallery (Spanish captions)

Full video of the interview

Washington DC, November 15, 2020

This couldn’t be a more interesting time to interview Barack Obama, former US president, 2009 Nobel Peace Prize winner, former “boss” of the man who will be the next president, and one of the most important political figures of the century so far. The meeting with Obama took place on Sunday, November 15 in the Fairmont Hotel in Washington DC, with the social distancing and safety measures required by the current situation. The editor-in-chief of EL PAÍS, Javier Moreno, and a video team traveled from Madrid and Mexico to be able to offer the complete footage of the only interview that Obama has granted to a Spanish newspaper since the election victory of Joe Biden on November 4.

‘A Promised Land’

The first volume of Barack Obama’s memoirs, A Promised Land, was published on Tuesday. In it, the former president narrates his personal journey to becoming the leader of the Western world, describing in detail both his political experience as well as the key moments of the first stage of his historical presidency, an era of great commotion and of profound change.

Published in Spain by Debate.

If you want to support the creation of articles like this one, subscribe to EL PAÍS.

Subscribe here- Credits

- Coordination and format: Guiomar del Ser

- Art and design direction: Fernando Hernández

- Layout: Nelly Natalí

- English version: Simon Hunter

- Production: Carlos Martínez

- Image: Mónica González and Carlos Martínez

- Graphics: Eduardo Ortiz