American-style libertarianism comes to Spain

Trump’s position on the coronavirus crisis has found fertile ground across the pond, and various groups are emerging to take issue with the media, politicians and experts in the name of “freedom”

The restrictions applied by governments around the world to address the coronavirus pandemic have triggered ubiquitous popular protests. In Spain, the first ones began on May 10, on Núñez de Balboa street, in the upscale Salamanca district of Madrid.

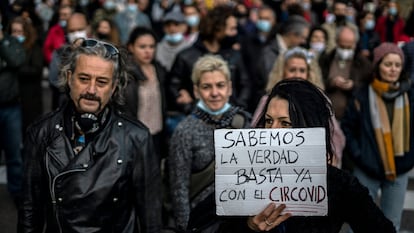

Others have since followed, besides those staged by professional sectors; there have been protests by the extreme right, by coronavirus deniers and even by vandals, not to mention the marches organized specifically by the far-right party Vox. What they all have in common is the word “freedom” in their slogans. The concept is striking – it clashes with defending the general public interest with regard to controlling the virus. It is also an exotic concept within the Spanish political scene, which is unaccustomed to the extreme demand for individual freedom that holds such sway in the US.

It is a concept has been incorporated into the general discourse adopted by the Spanish opposition, which has for months been accusing the center-left government of taking advantage of the pandemic to establish something akin to an authoritarian regime. On a recent Thursday in Congress, lawmakers for the center-right Popular Party (PP) and Ciudadanos (Citizens) and the far-right Vox cried “Freedom!” as the new education law was passed. “Freedom” was a word mostly heard during Spain’s transition to democracy in the late 1970s, a time when a band named Jarcha sang of Freedom without fury, calling for national reconciliation. Now the cry for freedom is uttered with fury.

“My theory is that lifestyles have become Americanized and so have ideas,” says Daniel Innerarity, a professor of political philosophy and author of Pandemocracia. Una filosofía de la crisis del coronavirus (or Pandemocracy. A philosophy of the coronavirus crisis). “The influence of the American think tanks has been filtering in. And it rubs off if you watch Clint Eastwood films, for example, which are great and have a clear political message that is very republican and libertarian – the idea of a freedom with no rules, assuming one’s own risks and not trusting the paternalism of the state.”

My theory is that lifestyles have become Americanized and so have ideasDaniel Innerarity, professor of political philosophy

The implication is that the most extreme form of American libertarianism, which culminates in Trump, is finding its way to Spain. “The American citizen has not completed the transfer of his sovereignty to the state,” explains Innerarity. “He keeps weapons at home, he does not want public healthcare. And, as in Clint Eastwood films, this is still compatible with the idea of occasional compassion, and rebellion against injustice.”

What is taking place is a crucial debate between two cultural traditions, the European and the Anglo-American. In one case there is a protective state, and in the other the state has been reduced to the bare minimum. It is also the classic distinction established by Isaiah Berlin in his 1958 essay Two Concepts of Liberty between negative and positive freedom. In one case, the others cannot do what they want with you, there is no domination and your freedom is protected; in the other, you can do whatever you want and you see rules as restricting your freedom.

“Here in Spain we are closer to the French tradition, where the state decides many things and individual freedom is balanced against the common good,” explains Ignacio Sánchez-Cuenca, director of the Carlos III-Juan March Institute of Social Sciences at Carlos III University in Madrid. “Catholic societies are the least individualistic, while Protestant societies, which have a direct relationship with God, have seen stronger forms of individualism develop. Now, in Spain, Trump’s extremism is having an influence. It’s a little borrowed, but maybe it’s the seed of something.”

Shedding light on the phenomenon are activists such as Sonsoles Queipo de Llano, 25, who lives on Núñez de Balboa street and who promoted the protests on May 10 by posting videos on Instagram, “Honestly, until the Nuñez de Balboa events happened, I deliberately steered clear of politics,” she says. An economics graduate who is now studying psychology, she goes on to explain that her political awakening took place at a very specific moment and came in the form of the police.

It is a perfect metaphor – the police as representatives of the state’s monopoly on violence. The officers showed up after a neighbor reported people who had gathered in the street to listen to music coming from a balcony. “As far as I’m concerned, the police have always been the good guys, but suddenly they treated us like criminals. It was a really horrible feeling and very disappointing,” she says. “We all had the feeling we were being locked up, that we were helpless, and not only on my street; people from all over Spain wrote to me about it.” She got about 400 messages. And while the general consensus is that important decisions are in the hands of politicians, she points out that “we have more power than we are led to believe.”

Queipo de Llano –not a direct relative of Franco’s general Gonzalo Queipo de Llano who rose to prominence during the Civil War – says she’s not a coronavirus denier. In fact, she had the virus in September and now donates her antibodies. “What I am arguing against is the notion that the way things have been done is the only way,” she says. “I appreciate common sense rather than imposed rules. The conflict between freedom and health is a huge lie that we’re being asked to swallow: that we have to choose between freedom or saving lives.”

Queipo de Llano believes there have been many “unjustified” measures and, regardless of the political stripe of the government in power, she believes that the key is “transparency and clarity” – neither of which she considers to have been achieved in Spain. “The government had a 2005 pandemic protocol that it could have applied and did not apply [she is talking about an existing national flu pandemic response plan], and it had information that it did not pass on to the public,” she says.

The conflict between freedom and health is a huge lie that we’re being asked to swallow: that we have to choose between freedom or saving livesSonsoles Queipo de Llano, student

This flags up another key element of the libertarian trend observed by Innerarity, namely a general and profound crisis of confidence. “A major problem is that social and public trust has been eroded – nobody trusts anybody,” he says.

According to Queipo de Llano, “politicians have lost people’s trust – they are detached from reality. The main objective of politics is to divide: left and right, fascists and progressives and, while the citizens are split by these wars, the politicians do what they want.” Given this state of affairs, she feels she is thrown back on less traditional courses of action. “I call it my political volunteering,” she says. “I have learned a lot these months about both politics and the law. I am the mouthpiece for protests, solidarity, organizing, coordinating.” She does everything via Instagram and works with a group of about 50 volunteers. “We have to get civil society back,” she says. “We can change things.”

After the neighborhood rebellion in Nuñez de Balboa, an association called Police Officers for Freedom was formed. Its spokesperson is Sonia Vescovacci, 41, a national police officer on sabbatical who has made videos calling out internal problems within the police force. In September, she became the face of the association, which has around 300 members, many of whom they claim belong to various law enforcement agencies, including the fire service. The association basically disagrees with having to enforce laws and impose fines that it considers unfair. It even advises people on how to appeal against sanctions. “It is true that there are some laws we have to comply with, but we cannot comply with any law, at any price,” says Vescovacci in one of her videos. According to an anonymous police officer, “this has all been cooked up by the politicians. I didn’t become a policeman to make people afraid of me if they haven’t done anything – for not wearing a mask, which does no good; for breathing. I became a policeman to defend freedom.”

“As police officers we have to safeguard freedoms and rights, and we can see that articles of the Constitution are being violated and that we are collaborating in depriving citizens of their freedom. This is a state of exception under a different guise, with no legal basis,” says Vescovacci, alluding to the state of alarm – the lowest of three emergency states contemplated in the Constitution – recently introduced for the second time in Spain to support restrictions on mobility to curb the spread of the coronavirus.

As police officers we have to safeguard freedoms and rights, and we can see that articles of the Constitution are being violated and that we are collaborating in depriving citizens of their freedomSonia Vescovacci, police officer on leave

Vescovacci stresses that they are not deniers, but they do question the scientific effectiveness of masks, for example. “Prolonged use has side effects: physical and psychological damage, anxiety, reduction of oxygen, dermatitis and an impact on neuron development,” she says, adding that she has access to studies that prove it. Again this has to do with the general crisis of confidence because the assumption that the authorities and experts know what they are doing is being questioned. “That’s the problem,” she says. “That you accept things instead of investigating on your own.” In this search for an alternative truth, they quote people like Josep Pàmies, a controversial farmer from Lleida who presides over an association for alternative medicine and sells a sodium chlorite product to combat the coronavirus called Miracle Mineral Supplement (MMS), which is banned in Europe. “We are open to any kind of ideology and check things out for ourselves,” she says. “I have colleagues who consume MMS and they’re doing really well. Because we depart from what is on the news, we are classified as different.”

Protests under the single, simple concept of “freedom” allows for a nebulous ideology. It is a protest against the media, politicians and experts, who are not to be trusted. And personal mobilization is exciting, something that was close to impossible before social media. But when did these libertarian ideas take root in Spain? “It had already begun a little with Zapatero [the Socialist Party premier from 2004 to 2011], this resistance to power when the power is managed by the left,” says Innerarity.

These days, the PP has started to claim that Spaniards are living in a dictatorship. Within the conservative party, the Madrid branch has always been the most neoliberal in its views, allowing for former regional premier Esperanza Aguirre’s policies of privatization, for example – a tradition of which today’s party president, Pablo Casado, is a product.

This cultural conflict moved up a gear a month into lockdown on April 23, when the International Foundation for Freedom (FIL) launched its manifesto Do not let the Pandemic be a Pretext for Authoritarianism, promoted by its president, the writer Mario Vargas Llosa. The document was signed by 150 high-profile figures, including former PP premier José María Aznar and former Ciudadanos leader Albert Rivera. A passage of the manifesto reads: “In Spain (...) leaders with a marked ideological bias intend to use the challenging circumstances to monopolize political and economic prerogatives that in any other context citizens would resolutely reject.” This narrative was quickly espoused by the opposition and ended up as a general cry on the streets. On May 16, a large canvas covering a building in Madrid appeared with the Spanish prime minister, Pedro Sánchez of the PSOE, depicted as Big Brother. The term “Orwellian” has become commonplace.

According to Ignacio Urquizu, the Socialist mayor of Alcañiz (Teruel), as well as the author of a 2019 analysis on the average Spaniard called ¿Cómo somos? (or What are we like?), one key to the libertarian trend is digitization, particularly now that we are locked up at home with fewer ideas exchanged face-to-face. “We have all become digitalized and these ideas are on digital platforms, on the networks – you don’t see so much of them in the traditional right-wing newspapers and media,” he says.

Urquizu adds that in 2004 he was living in the US, and many of the extravagant claims that appeared in blogs written by extremists there have since made their way to Spain. “It’s [a movement] led by several digital media and radio stations,” he says. “That’s why you find that people you know are suddenly trotting out these slogans. It’s a right wing closer to Vox than to the PP. And it’s curious because it was [former PP prime minister José María] Aznar that introduced this right wing, which is more Anglo-Saxon and more Republican, with a different concept of freedom from that of a French or German conservative.” Urquizu points out that Aznar did not so much step towards the center, as shift closer to the US through an immersion in ultraconservative universities and organizations, such as the Cato Institute in Washington.

It’s just an anecdote, but in 2007 Aznar made a memorable speech about wine in which he also referred to traffic fines: “I don’t like people saying to me: ‘You can’t go faster than this given speed limit; you can’t eat hamburgers of a certain size; you must avoid this and besides, I forbid you to drink wine.” Political scientist Ignacio Sánchez-Cuenca agrees that through his Foundation for Analysis and Social Studies (FAES), Aznar has been planting the seeds of libertarianism. “I don’t think it’s that bad, although those who introduce it at protests tend to be the nuttiest ones. And I’m surprised at how little debate there has been in Spain when we were told not to leave our homes. It’s been accepted very quickly. The public shows great deference to the state. It allows itself to be herded. It is not unhealthy to have a debate.”

The director of FAES, Javier Zarzalejos, meanwhile, laughs at these conclusions. “No, no, FAES has very little to do with libertarianism and ultraliberalism,” he says. “This individualism is more the product of cultivating leftist thought – the idea of the individual’s absolute capacity of determination is very 1968 – the forbidding of forbidding, a radical individualism that does not accept legal or moral restrictions. FAES tries to claim freedom while others try to claim the sovereignty of subjectivity.”

This is not a political proposition, it is simply a populist narrative. Americanization without Americans can be a caricatureJavier Zarzalejos, FAES director

Now a member of the European Parliament for the PP after serving for eight years in the Aznar administration, Zarzalejos is also not surprised by the protests. He believes that they are normal, “taking into account that we have had to face very challenging cultural concepts: the state of alarm, lockdown – and let’s see what happens with the vaccine.” Referring to the protests, he says that “they have overtones that are folkloric, extremist, denialist and conspiratorial and linked to massive disinformation strategies. But it seems to me that what is important is the social discipline that most of us have shown.” What he perceives in the protests is “a chaotic mix of strictly anti-government positions, of feeling fed up,” but he does not believe that they will evolve into anything significant. “This idea of freedom that is basically being claimed is one of pure subjectivity, not a claim on an institutionalized freedom within the system. It is of the ‘Why should you tell me what to do?’ variety – the sovereignty of the subject rather than of freedom.”

Regarding the contrasting concepts of freedom on the left and right, Innerarity points out that each camp has its own triggers. “For example, a person on the left will be annoyed by feeling excluded from the decision-making process. But a right-wing person will be more bothered by being told what to do,” he explains. “In a traffic jam, there is always someone who complains that there is no police, and someone else who says the jam is the police officer’s fault. One thinks that where there is no authority things are going badly, and the other thinks that too much authority is a problem.”

Regarding the opposition’s attitude, Zarzalejos believes it is its duty to counterbalance a government that “has done very questionable things, has behaved arrogantly and has not been very transparent. Given the seriousness of the situation, there has been no institutional fair play that could generate confidence, and that has undermined parliament.” He does believe that the US might have something to do with the emerging libertarian trend while adding that there is a fundamental difference between what’s going on in the two countries. “This is not a political proposition, it is simply a populist narrative. Americanization without Americans can be a caricature.”

He explains that in the US, the tradition is to stand up not so much for the individual as for the local community, which is self-regulating. “That does not exist in Spain,” he says. “Here we pretty much like the state. The average Spaniard, according to studies, believes the state has an obligation to sort out their life.”

English version by Heather Galloway.