Instructions for learning how to shut up

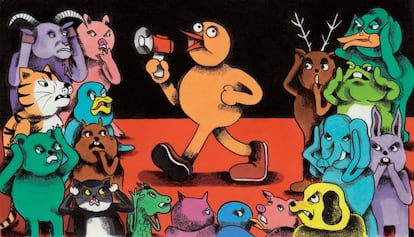

We talk more and more, and the worst part is that, according to multiple studies, we mostly talk about ourselves. After years of verbiage fueled by all kinds of platforms and social media, the time has come to be quiet. Now, there are courses to teach us how

Therapy to make us shut up. Books to convince us that silence is increasingly valuable. Gurus who promise to cure us of our urges to say everything, everywhere. After a decade of training and learning to be loud on the internet, in 2023 we are being told that talking less accomplishes much more. A book on this subject is a New York Times bestseller and Time magazine made the topic a cover story.

At the beginning of this year, there were over two million podcasts with 40 million episodes produced, over 3,000 TED talk events, tens of thousands of Instagram reels, 7 billion daily audios on WhatsApp and countless autofiction videos, where everyone tells their own truths. We are living in a global epidemic of verbal diarrhea.

And what do we talk about when we talk too much? Well, almost always about ourselves. And we like it. We especially enjoy it when we have an audience. Research from Rutgers University found that, on average, we tend to spend 60% of the time in a conversation talking about ourselves; this figure can reach 80% on social media. The reason we do that is simple: we love it when we are the center of the conversation (and in control of it). Through magnetic resonance imaging, a team of researchers at Harvard University’s Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience lab observed that talking about ourselves activated the reward and motivation circuits in the brain; these are the same ones engaged by sex, drugs and good food.

Pleasure hooks us, and some people cannot ration their speech; they are real junkies of small talk that almost always ends up — surprise, surprise! — being about themselves. As American writer Dan Lyons tells it, he was one of those people. In his bestselling book STFU: The Power of Keeping Your Mouth Shut in an Endlessly Noisy World, he confesses that he was a talkaholic and, like a good addict, he was unable to stop himself. He was “mansplaining, maninterrupting and deliver[ing] manmonologues,” he recounts in his recently published book.

In 1993, West Virginia University researchers James McCroskey and Virginia P. Richmond coined the term talkaholism to describe the addiction to compulsive chatter. They also created a diagnostic test for talkaholism (by the way, Lyons scored 50 points). McCroskey and Richmond described talkaholism as an addiction. As Lyons writes in his Time magazine article, “talkaholics cannot just wake up one day and choose to talk less. Their talking is compulsive. They don’t talk just a little bit more than everyone else, but a lot more, and they do this all the time, in every context or setting, even when they know that other people think they talk too much. And here is the gut punch: talkaholics continue to talk even when they know that what they are about to say is going to hurt them. They simply cannot stop.” In 2010, Michael Beatty, a professor at the University of Miami, discovered that the origin of this compulsion was an imbalance in the brainwaves of both hemispheres that affect impulse control.

Among the traits that characterize talkaholics is disregarding one of the first rules of coexistence we learn as children: waiting their turn (both in general and specifically in terms of speaking). According to experts, they implement a tactic known as a shift response that consists of constantly diverting the focus of any conversation until they return the discussion back to themselves. Most consider themselves to be good conversationalists. They love it, but they lack the ability to edit their stories, which are often endless and full of extraneous details, digressions and interruptions.

Mostly normal people can also be addicted to narcissistic and unsubstantiated chatter on the internet. We talk and tell so much that sometimes guilt eats away at us. Nearly 40% of internet users aged 18-35 have regretted posting information about themselves online at least once, and 35% have regretted talking about a friend or family member more than they should, says the Digital Life study conducted by the Havas Creative agency.

Resisting social pressure and not engaging in or removing oneself from global chatter requires training. People who have decided to learn to be quiet are now signing up for listening courses, many of which are cropping up on the internet. For his part, Daniel Lyons learned the techniques they teach prisoners to keep their mouths shut during parole hearings from a California psychologist.

In this day and age, it is difficult to overcome the urge to fill each silence we encounter. The result is thunderous noise and endless chatter. If we could at least limit ourselves to speaking only about what we know — which does not include talking about ourselves because we have mastered that subject the least — it would be a great relief. Learning to be quiet, resisting the urge to tell things, is 21st-century gold, the new Google, the cryptocurrency that does not vanish. It’s also a status symbol that New York Times bestsellers call a superpower.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.