Should Spain’s bars and restaurants be allowed to ban children?

Balicana in Bilbao has become the latest establishment to become a child-free zone, a move that has sparked indignation from consumer groups, who say it is discriminatory

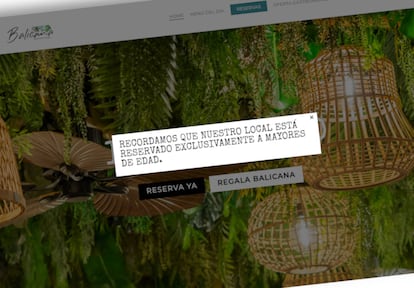

Should children be taken to bars? What responsibility do parents have if their children go with them? Is there really such a thing as “childphobia” or, as it is sometimes known, paedophobia? These are questions that arise every time an establishment decides to ban minors from setting foot on their premises. The latest case concerns Balicana, a restaurant in the Basque city of Bilbao that has been criticized by FACUA-Consumers in Action for not allowing children access. On its webpage, Balicana clearly states that its premises “are reserved exclusively for adults.” But according to the consumer association, barring entry to an establishment on the basis of age is discriminatory abuse of the rights of admission and at variance with the law that allows children into bars and restaurants if accompanied by a responsible adult. Consequently, FACUA is demanding that the establishment be fined and is encouraging the public to report any similar norms in other bars or restaurants.

Balicana is not the only restaurant in Spain to ban children. Some of these establishments claim that the presence of children is disruptive, increases the noise level, and argue that parents often fail to supervise them properly. These restaurants prefer to avoid these issues and have opted for an adults-only scenario, despite the indignation of parents who want to be able to dine with their children; and despite the legitimate right of minors to enter.

Is there such a thing as childphobia?

“Childphobia has existed since the beginning of time,” says Berna Iskandar, a journalist specializing in motherhood, parenting and children’s rights. “Kids are the most vulnerable members of society and cannot defend themselves. There is a real ignorance among adults surrounding the needs of our youngest children who are supposed to meet expectations that do not correspond to their age. Childhood is a stage of intense development during which they have to experiment.”

Iskandar explains that the way to eradicate the fear of children is “by building more child-friendly spaces where their rights and needs are taken into account; cities and bars that adapt to them and not the other way around. Just as spaces are adapted to people with difficulties, with ramps added, for example, they must also be adapted so that children can develop and relax, both of which are vital to them.”

According to Iskander, when there is discrimination, as in the case of the restaurant in Bilbao, it is up to the adults to fight the injustice. “If we build places and spaces that are more child-friendly, it would help both children and adults to enjoy themselves,” she says. “The goal is clear: we have to move from an adult-centered society, as is currently the case, to a child-centered one.”

It is, she says, the parents’ responsibility to attend to their children’s needs and go to places where the child can also enjoy themselves. “If the child is upset, the parents should be attentive and spend time with them,” she says. “The reality is that we are in a constant rush and children are expected to meet schedules imposed by adults. We do not spend time with them; we are not with them; we abuse screens, material things and our children are alone.”

While Iskander does not believe that children have worse upbringings now, she does point out that things were very different in the past. “There were more open spaces before,” she says. “And children had more opportunity to play and move around, so they would be more relaxed when they got home at mealtimes, for example. Now they live more indoor lives and have to contain all the energy that comes with childhood. Making them the focal point should be a priority.”

The rise of the child-free zone

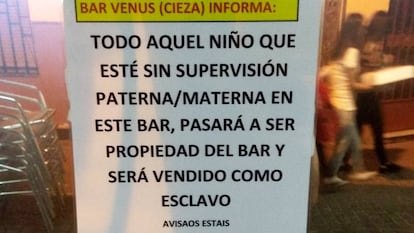

Cases similar to that of the restaurant in Bilbao occurred in 2018 and 2019 in Murcia, Salamanca and Vigo, with hospitality establishments making it clear that children were not welcome. In Murcia, the owner of a bar called Venus put up a sign that said: “Any child who is not supervised in this bar by his mother or father will become the property of the bar and will be sold as a slave.” The sign sparked a significant amount of controversy, especially over the word “slave.” The owner, Manuel M. Villalba, told EL PAÍS at the time that it was a joke and that he in fact adored children. But, he explained: “Parents are having a drink while their offspring are making life impossible for others.”

In Salamanca, meanwhile, a bar called Livingstone printed a series of rules whereby children had to be with their parents at all times; could not bring a toy from home or even cry. The move created so much controversy that the restaurant was forced to withdraw the norms. In Vigo, the restaurant Beach Escola Vao cut to the chase with a sign that read “Child-free zone” and invited patrons to enjoy “the quiet.”

“There is an adult-centric vision of society in general,” says Esther Vivas, author of Mamá Desobediente (or, Disobedient Mom). “We live in a society that has a very hypocritical view of childhood. On the one hand, it praises and glorifies childhood, as in the cute and well-behaved children we see in advertising, but at the same time, it turns its back on the needs of children and the fact that they behave like children. When they start laughing, running and being inconvenient, we want hotels, bars and spaces that are free of them.”

So why do some adults find children annoying? “Simply because they are children,” says Vives. “We live in a society that is absolutely focused on productivity, the market and economic profit, in which dependent people are a nuisance. This is the main cause of childphobia,” she says, adding that the system does not allow children to be children: “It denies their rights.”

Vives, who is also a sociologist, maintains that under the existing adult-centric vision, children are forced to behave like adults in a system that punishes them. This has been particularly evident during the coronavirus pandemic, she argues. “At first, at the beginning of the crisis, children were said to be super-spreaders,” she says. Scientific studies later showed the claim to be untrue. “As the most penalized members of society during the crisis, they were locked up at home for weeks and forbidden to go out and socialize with their peers. And even now, at a time when it is possible to go out for a drink with friends without a mask, any child over six still has to wear a mask at school, including during recess. It is flagrant discrimination and proof that childphobia is a reality.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.