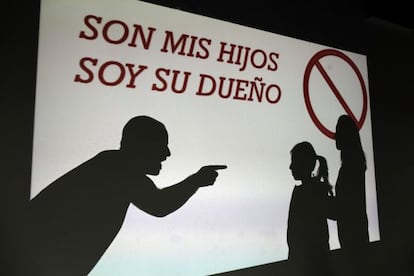

Parents, not owners

The right to raise and discipline a child stops short of physical and emotional abuse Determining the exact limits, however, is not easy Part of the problem is that punishment today often arrives too late and is poorly administered

They're my kids. I own them," Homer Simpson explained to his wife after randomly punishing his children in an episode of the show parodying parent-child relations of some generations ago. Since those days gone by, the balance of power has shifted. Today, one might say it even favors children.

A 2008 change in Spain's civil code eliminated an article stating that, "Parents may discipline their children within reason and with moderation," which means that today physically punishing a minor is a criminal act, as is causing "psychological damage." Authorities concur that limits between discipline and abuse must be dictated by common sense, but this is not always clear as various cases in Spain, and their accompanying court verdicts, have proved.

The recent public debate concerning the issue is centered on a case in the southern city of Úbeda in which two parents were arrested after grounding their daughter for a weekend. At first glance, this may seem excessive, if it weren't for the fact that the daughter later claimed that she had been locked up and beaten, acts which clearly transcend punishment to more closely approximate abuse.

There is some confusion surrounding the case, however. The Andalusia ombudsman, José Chamizo, says the girl was held in a house that was still under construction and that her father brought her food "two days a week." The teenager, who reportedly had a bruised eye, escaped and later reported the incident to the Civil Guard. "You're not allowed to raise your own daughter," her mother later complained to the local press. The Andalusian equality welfare commissioner, Micaela Navarro, backed a decision to "immediately remove the minor from the family home due to possible risks" to her welfare.

The case highlights two interlinked issues: the aforementioned legal aspect and another related to childraising in general. Regarding the second, experts agree that punishment may be necessary at times, but that it is quite often applied too late, and is ineffective if the minor has not been disciplined throughout his or her childhood. Guardians must know how to exert their authority so that children understand and adopt different ways of behaving, varying the level of strictness according to each situation while remaining consistent.

There is no one single model. What works with one child may not work with another, says Helena Trujillo, a psychologist with Grupo Cero Clinic.

"Our children are not our private property. Many parents want complete autonomy in disciplining their children, but this is something that must begin when the first signs of disobedience appear. In order to avoid things getting out of hand, communication should be encouraged from the time the child is small; parents must get to know their children and their friends, and be involved in their interests on a daily basis. But not from the perspective of spying, but rather in a way that promotes an atmosphere of trust. That way, when the child reaches adolescence, an age in which they often lose their way, they won't be afraid to turn to their parents," the psychologist explains.

This must all be done within the limits set by the guardians. The problem, says Pepe Rodríguez, a doctor in psychology and professor at Barcelona's Autónoma University, is that these limits are often not clearly established. "Then the child becomes a sort of boss who does whatever he or she wants. Children must be taught the rules of coexistence at home so they know they cannot act on whatever whim they might have. They are not going to learn this at school - teachers just do not have the authority. If the child is told off at school, the response is: 'Just wait. Tomorrow my mother will come in and then you'll see.' And the worst thing is that this threat is followed through," Rodríguez says.

He believes that there are some things that cannot be resolved through talking it through with a teenager, and that in some circumstances, the best option for parents is to take away the child's privileges. The law only stipulates the provision of basic necessities so cellphones and video games can be taken away, and trips and going out can be restricted if the child does not behave accordingly.

Punishment is necessary if the situation calls for it. But it should be instructive in nature, says María José Díaz-Aguado, a professor of educational psychology at Madrid's Complutense University. "It should be applied in order to assist the child in changing an inappropriate behavior," she says, while warning of the risks involved. "It is a measure that can cause rejection of the person doling out the punishment."

Díaz-Aguado adds that sometimes children are asked to change their behavior without understanding what it was they did wrong - a counterproductive measure. She gives an example: "If a child is sent to their room because they got bad grades, the indignation caused by the punishment may negatively affect their ability to concentrate while studying. It's better to try and understand why the child failed, how he or she organizes his or her time, and then take corrective measures that are consensual. This is more effective in helping teenagers understand that their actions have consequences. It's also usually better to reward positive behavior rather than focusing only on things that must be avoided."

Díaz-Aguado headed up a 2010 study by the State Observatory for Coexistence at School in which 11,000 parents of middle school children were interviewed on various aspects of childraising. It showed that families prefer the use of dialogue to deal with conflict. The top solution by far (chosen by 71.9 percent) was to "assess why each case had arisen and help the student resolve the issue in a different way." This was followed by "helping the punished child to predict the consequences of his or her inappropriate behavior and the damage it may cause," (40.2 percent). Only 6.6 percent of parents chose "applying the level of punishment that most closely corresponds to the inappropriate behavior," while 10.4 percent chose "more strict enforcement of the rules."

This reflects a shift in society, says Díaz-Aguado. "Rejection of authoritarianism has grown. For parents, the best measures are those considered to be coherent with democratic values: communication, reasoning, respect for a person's dignity, persuasion, and respect for boundaries. But this is contradicted in practice. The majority of families continue to justify striking a child as an effective means of disciplining them," she says.

And this is where the legality of the issue enters the equation. Can or should a parent hit his child? Juvenile public defender for the Madrid region, Arturo Canalda, says it's important to distinguish between "a spanking, which is of no great consequence, and the habitual use of this method for disciplining or when it goes beyond a mere slap." He feels that those who interpret the change in the civil code to mean that minors may no longer be disciplined are as mistaken as those "who think that before it was okay to hit them." Canalda believes that the current law is adequate and should be interpreted according to the circumstances.

There is, however, a lack of agreement on the issue. Maite Salces, a legal assistant with the children's ombudsman for Andalusia, says there are gray areas. "To what extent do parents have legal authority in disciplining? Where is the line in defining which actions constitute emotional abuse?" she asks. Salces says that under the current code a slap may be prosecuted under the law as assault and gives the example of a mother in Jaén who received a restraining order against her son in 2006 after slapping him. The sentence determined that the mother "committed assault against her son when she grabbed him by the collar to lift him off the floor and struck him on the head." The judge felt that the mother's actions fulfilled the definition of abuse, "even though it was an isolated act of assault."

The woman was subsequently sentenced in 2008 to 45 days in prison and forbidden to see her son for a year. A few weeks later, after strong public protest, the woman was granted a fast-tracked pardon in order to prevent the separation of mother and child.

Javier San Sebastián, head of child and youth psychiatry at Madrid's Ramón y Cajal Hospital and president of the O'Belén Foundation, which oversees a number of centers for minors, is very critical of the current state of affairs. Although he feels that the law for the protection of minors clearly establishes the rights of children and adolescents, he believes that it is not explicit enough.

"It states that a minor has ample rights, but [...] it doesn't mention responsibilities. There is a legal void. With the significant social changes that have occurred, what we are seeing now is that there are a number of very problematic juvenile offenders whose parents do not have the means to keep them in check, restrain them or restrict their behavior," San Sebastián says. He agrees with the Andalusia and Madrid ombudsmen in that the most common scenario is not that of a child suffering from abusive punishment but that of parents overwhelmed by unmanageable children.

"If a minor knows that the government is always going to choose their side over that of their parents, they can take advantage of it. Some guardians find themselves in a situation where they just do not have any way of disciplining the children under their care," says San Sebastián.

Psychologist Pepe Rodríguez, who has seen numerous families with problems disciplining their children pass through the doors of his office, says much the same thing. He gives two dramatic examples: an adult son, with a job, who continuously "poked fun at his mother." She could not force him out of the family home without first going to court. A second case involves a mother who was sentenced to eight months in jail for "slapping her hysterical daughter."

"The excessive protectionist and intrusive nature of the legal framework in this country has resulted in atrocities. There are families that are terrorized by children who have all the rights in the world but no responsibilities. There is a legal-educational error. There is a big difference between abuse or torture and a spanking. Violence is not instructive for anybody. Slapping your child is not, in general, recommended, but there are times when it could be. We need to restore sanity," says Rodríguez.

The former Socialist government employed a group of experts to draft the law for minors and to determine other related issues that were still up in the air. The results of their work, however, never saw the light of day. But Javier San Sebastián, who formed part of the group, says it established responsibilities and otherwise "filled in the gaps in how the administration should manage the protection of minors."

Roncesvalles Barber, a filiation authority who teaches civil law at University of Rioja, believes that legally establishing the limits of parental authority or that of the government in this area is a "very sensitive" issue. Some regions such as Catalonia and Aragon have approved broad regulations. In any case, Barber believes that throughout Spain "there are ways to ensure fair custody practice." But could they be improved?

"I'm not sure that legislation that takes in all possible scenarios would be beneficial. General provisions, which allow judges to take the measures that best correspond to each specific case make more sense," Barber says, adding: "Laws that lay out in writing what is common sense worry me. A profusion of laws does not encourage their compliance and if we have a lot of laws that are not abided by, we stop believing in them."

Custody must be carried out in line with the objective established by the law: the protection of children, says Barber. This, she says, must be the first legal condition. Parents must be capable of fulfilling this function, and if they are not, or if they become abusive, the government is responsible for ensuring the care of the minors. Contrary to what Homer Simpson believes, our children are not our private property.

Iron fist in a velvet glove

- Professor of educational psychology María José Díaz-Aguado, who has studied the subject of punishment and its alternatives in depth, provides here a list of practical tips for the appropriate disciplining of children.

- Rules must be clearly defined and consistently enforced. Children should be active participants in defining the rules and in establishing the disciplinary action to be taken if the rules are not followed.

- Permissiveness with extreme behavior must be avoided so that children do not interpret this as implicit approval. The effectiveness of the rules is diminished when serious transgressions are overlooked.

- Discipline must be aimed at changing behavior patterns and helping children understand why some are inappropriate. Beyond bringing about the desired behavioral change, the children should be made to feel remorse for their acts so they want to repair the damage they have caused.

- In order to prevent the reoccurrence of inappropriate behavior, alternatives must be provided.

- Discipline should be aimed at fostering the children's ability to put themselves in the shoes of those they have hurt, thus encouraging the development of this very important human capacity.

- Constant bickering over relatively unimportant misconduct should be avoided.

- Disciplining should not be decided in the heat of the moment. It is better to avoid tense situations and to reflect. It should also target specific behavior and not include generalized negative statements or any that may lead the child to question the parent's unconditional love. One-sided conversations should be avoided in order to encourage the child's participation; it is better to create an environment in which children are able to explain their actions and reflect on them so they can change their behavior.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.