Researchers announces the discovery of a new species linked to the origin of humankind

The fossils, attributed to an unknown australopithecus that lived in present-day Ethiopia 2.6 million years ago, have met with skepticism from other experts

Fossil hunter Omar Abdulla used to carry an AK-57 assault rifle as he roamed his dangerous homeland, the desert region of Afar in Ethiopia, contested by rival tribes. On Valentine’s Day 2018, while descending a hill, Abdulla shouted: “Oh my God!”

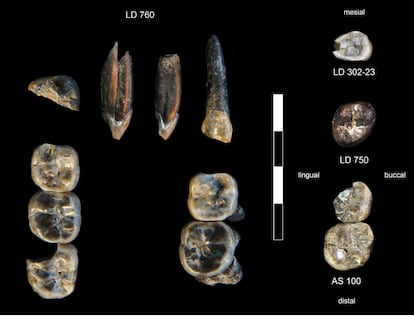

U.S. paleoanthropologist Kaye Reed recalls running toward him and finding him picking up a fossilized tooth from terrain dated to about 2.63 million years ago. They continued walking and discovered more teeth. Abdulla was killed in 2021 in an armed confrontation, but Reed and her colleagues continued studying those teeth and now announce that the remains belong to a previously unknown species of australopithecine that coexisted in present-day Ethiopia with early humans.

The discovery, published this Wednesday in the journal Nature, sheds light on a particularly obscure period of human evolution. Three million years ago, only one genus existed in East Africa: Australopithecus. By 2.5 million years ago, there were three: Australopithecus, Paranthropus, and Homo, the scientific label for humans.

“It was an exciting day,” Reed recalls. Her team ended up finding about a dozen unusual teeth, large in size and with subtle morphological differences. They didn’t match anything previously known.

The last known Australopithecus afarensis — like Lucy, the famous female whose remains proved that these human ancestors already walked upright — lived around three million years ago. Perhaps these were the first Australopithecus garhi, another species that lived in present-day Ethiopia 2.5 million years ago, but the teeth were different.

For Reed and her colleagues, there is only one hypothesis that fits the data: a new species of australopithecine, still unnamed. “We need to find something with more characteristics, like a skull or a skeleton. I wish we had that already,” explains the researcher from Arizona State University.

Two decades ago, Reed worked at the Paleolithic site of the Sopeña cave in the Spanish region of Asturias. She fell so in love with the place that she decided to spend a sabbatical year there between 2005 and 2006, living in the village of Benia de Onís and walking every afternoon along its shepherds’ paths.

Three years earlier, Reed had launched a research project in Ledi-Geraru, in Ethiopia’s Afar region. In March 2015, her team announced that they had found there a fragment of a jaw with teeth, attributed to an individual of the genus Homo who lived around 2.8 million years ago. According to their report in Science magazine, it was the earliest known human.

In addition to the 10 australopithecus teeth, Reed and her colleagues have found three more teeth that they believe belong to an unidentified human species, dating between 2.59 and 2.78 million years ago. The team argues that their discoveries demonstrate that these lineages lived in the Afar region at the same time. Did they coexist? Did they fight? That is unknown.

Reed emphasizes that the classic view of human evolution — as a straight arrow from ape to Homo sapiens, passing through Neanderthals — is completely wrong. The paleoanthropologist describes a “bushy tree,” where branches cross and intertwine, with species that lead nowhere and simply go extinct.

U.S. researcher Tim White, a living legend in prehistory, believes that the new conclusions are unconvincing. As a young man in 1979, White was one of the scientists who announced to the world the discovery of Lucy, the one-meter-tall, small-brained Australopithecus afarensis who walked upright around three million years ago in what is now Ethiopia.

White notes that the Ledi-Geraru area is only a few dozen miles from Hadar, where Lucy’s partial skeleton was found. As a result of erosion, White explains, Hadar has no sediments from around 2.7 million years ago, whereas they exist in Ledi-Geraru.

The paleoanthropologist argues that the new teeth fit into the lineage that evolved over half a million years from Lucy and other Australopithecus afarensis individuals to their “direct descendants,” the Australopithecus garhi, a species that White and five colleagues described in 1999 as a possible ancestor of early humans.

“The authors incorrectly claim that the last appearance of Australopithecus afarensis was 2.95 million years ago. Consequently, they make the extraordinary assertion that they have discovered a new species, instead of the expected evidence of the evolution of Australopithecus afarensis,” White contends. In 2022, he moved to the Spanish city of Burgos to join the National Research Center on Human Evolution (CENIEH).

“The authors’ claim that it’s a new species of Australopithecus is even less convincing than their parallel 2015 claim in Science that a jaw fragment from their study area represents the oldest Homo, at 2.8 million years old. I expect both claims to be refuted when new fossils are discovered,” adds White, who is highly critical of the peer-review processes of these scientific journals. “It’s more reasonable to interpret both the jaw and teeth as belonging to more recent, slightly evolved members of Australopithecus afarensis, Lucy’s species. However, it seems that such a conclusion would not satisfy Nature’s apparent need for paleopublicity,” he concludes.

Researchers Marina Martínez de Pinillos and Leslea Hlusko, also from CENIEH, are currently studying fossil teeth from Omo, in southern Ethiopia, attempting to determine whether they belong to Australopithecus or Homo. Their preliminary results suggest that isolated teeth from this dark period cannot be identified with that level of specificity or certainty.

“During this 500,000-year interval, an evolutionary line from Australopithecus gave rise to Homo and/or Paranthropus," the pair note in a joint response to this newspaper’s query. “Hundreds of hominin fossils are known from this period, the vast majority from the same geographic region, and numerous teeth are present. These previously described fossils reveal a large overlap in dental variation during evolutionary transitions. The 13 new teeth do not display any unique features that differentiate them from the already known fossils of Australopithecus afarensis and the earliest representatives of the genus Homo.”

Martínez de Pinillos and Hlusko explain that, when working with isolated teeth, it’s easy to misinterpret the differences. No two molars are alike, but the line between normal variation within a species, gradual evolutionary change, and the existence of a new species is very blurred.

“From our perspective, the extraordinary claim that some of these teeth represent a new species of Australopithecus requires extraordinary evidence, and, unfortunately, this set of teeth doesn’t provide it,” they conclude.

María Martinón, the director of the CENIEH, is also skeptical. “Although the sample is important and describes in detail the morphological variability existing in the region, I believe it may be premature to conclude that it is a new species of Australopithecus. The differences with Australopithecus afarensis do not seem robust enough to me, and the traits analyzed show a wide overlap that could be due to local or temporal variation,” she says.

“I agree that the evolution of our ancestors was not linear and that we should be open to more complex patterns, with the possible coexistence of even different genera,” she continues. “This could be explained by adaptations to different ecological niches — such as variations in diet — which would have reduced direct competition between them.”

Manuel Domínguez Rodrigo, co-director of the Institute for Evolution in Africa affiliated with the University of Alcalá in Spain, has worked at exceptional African sites, such as Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania. This expert believes that the Ledi-Geraru teeth could belong either to more recent and evolved Australopithecus afarensis than Lucy, or to a new species “extremely similar” to it.

In his view, this discovery documents that at least four evolutionary lineages were “coexisting” in East Africa at the time the genus Homo emerged: Australopithecus, Paranthropus, the controversial Kenyanthropus from Kenya, and the nascent Homo, characterized by an increase in brain size, a reduction in tooth size, the use of stone tools, and meat consumption, according to the researcher.

“This indicates that it was a period of major environmental change that led to a reshaping of all the faunas that existed in East Africa, including the hominins [hominids with bipedal locomotion and upright posture]. Each of these branches is an evolutionary experiment. After two million years, only two survived: Homo and Paranthropus,” explains Domínguez Rodrigo.

The Paranthropus were similar to more robust australopithecines but went extinct just over a million years ago. Whatever the course of evolution and the competition among the multitude of coexisting species, only one remained: modern humans, whose only predator is Homo sapiens itself, as illustrated by the murder of Omar Abdulla, the man who discovered the first teeth at Ledi-Geraru that Valentine’s Day.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.