Are we unique in the universe?

Human life, and science as part of it, are based on certain mental schemes that we call paradigms, and which are sometimes broken to open the mind to new horizon

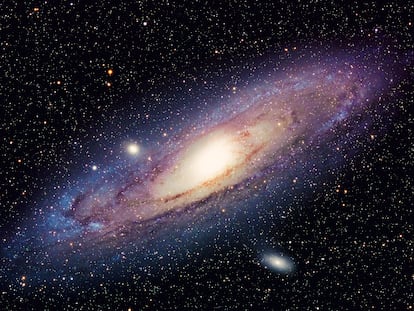

The chosen people. The grand destiny of a nation. The greatest empire ever seen in history. The center of creation. The pinnacle of evolution. These are phrases heard in different contexts — political, religious, even scientific — but all of them, in essence, reveal humans’ egocentric nature. In relation to these prideful visions of our world and the role we play in it, I am writing today what I would call the paradigm of life in the universe.

Paradigm isn’t a widely used word. On the one hand, there’s its more popular meaning, i.e. paradigm as a representative or clear example of something. For example: “James Dean, the paradigm of the young rebel.” But in science, paradigm has another meaning: it is a set of concepts that are taken for granted and around which an extensive range of scientific hypotheses is built.

In some of my articles, I’ve talked about axioms — truths accepted as self-evident without proof. A very basic axiom is that we can always add two numbers together and get another number, a constant result: two plus two equals four and it always equals four. It seems so basic that we would not dare to try to demonstrate it, but we can question the mathematical veracity of this axiom, or of anything, and their implications. Paradigms are similar, but more complex and elaborate than the most fundamental axioms, including mental frameworks, schools of thought, or established reasoning, about which there is a certain consensus (if only because of the impossibility of other reasons).

One of the most important paradigms in astrophysics is the so-called cosmological paradigm, which assumes that the universe is made up primarily of matter we cannot see, called dark matter, which is much more abundant than the normal (baryonic) matter that forms stars, planets, and ourselves. And separate from it is so-called dark energy. But I don’t want to dwell on that paradigm today, but rather on a more fundamental one for humans — a paradigm that is related to what I said at the beginning of this article. I am talking about the paradigm that life only exists on Earth. We would be the chosen people; the Earth would have a glorious destiny as the center of the universe — where the conditions for the emergence of life were met, culminating in evolution, of which humanity is the pinnacle.

If the sentences at the beginning of the article grated on us, those above should too as well. But we accept it as valid, almost at a reptilian brain level, and we live by them. If it weren’t a paradigm, what would be the point of many of the things we do and have done throughout history?

And now we move on to the astrophysical part of this article. Every paradigm, and every axiom, is assumed to be true without proof, but it may not be valid. As they are fundamental pillars, that are more or less complex, and give rise to many theories, it is not easy to falsify them (another word not widely used, but perhaps much needed these days). But if they are discovered to be invalid, and this triggers a paradigm shift, it leads to extraordinary scientific progress. An example is the shift from the Ptolemaic paradigm (the Earth at the center of the universe) to the Copernican paradigm (that planets orbit the Sun), which is not so different from the paradigm of life in the universe.

Paradigms are sometimes broken, and new ones emerge after a relatively long process of research on various topics, leading to scientific and even technological revolutions. At other times, the validity of a paradigm is actively sought. In the case of the paradigm of life in the universe, although the issue is complex, we have a whole range of experiments to either validate or disprove it. From Earth, we are attempting to understand how life arises, and we are exploring the same issue in space, through missions exploring distant worlds.

One of these missions, which last year entered its final phase of development at NASA and is now in limbo due to recent events, is Dragonfly. It is (or was?) scheduled to fly in 2028 and reach Titan, a moon of Saturn, in 2034. And there, its mission will be (or would be?) to study a unique world, with lakes and/or oceans and an atmosphere like Earth’s. But at temperatures around -180 degrees Celsius, those oceans are not made of water; instead, our vital liquid forms “rocks” on the surface or “lava” rivers that erupt from cryovolcanoes, and renew the icy surface. The liquids that survive at these temperatures are methane and ethane, which are gases on Earth.

However, the gases that make up Titan’s atmosphere are nitrogen (like on Earth) with “humidity” (i.e., diluted gas) and methane clouds. It’s a very different place from our planet, but one that has seas, where carbon compounds are everywhere and could give rise, with energy from the Sun and Titan’s active interior (which explains the cryovolcanoes), to the complex molecules needed for life to emerge. Perhaps there is no life there, or perhaps not the same kind of life, perhaps it is just one more step toward shattering our paradigm of life in the universe.

Dragonfly will be the second human-made flying craft to soar through the skies of other worlds. But while the Mars rover’s Ingenuity mission was primarily intended to demonstrate the viability of flying robots on space missions, Dragonfly will have several scientific instruments that will analyze Titan’s conditions at different points, separated by dozens of kilometers. It’s essentially a Mars rover that can fly. It will be able to analyze the atmosphere and take samples from different terrains as it moves across Titan’s surface, perhaps visiting a cryovolcano up close for the first time, as well as craters where meteorites have impacted and water may be present. If all goes well — and many of us are worried about its status right now — it should reach Titan in 2034 and reveal a new world in situ, a place very different from Mars, which has already given us spectacular images thanks to the rovers.

It’s very likely that Dragonfly won’t discover life, but it’s another step along the way. And what would happen if it’s discovered — or rather, I should say, what would happen when it’s discovered — that we’re not unique on Earth, that there’s life beyond our planet? Will the paradigm of life be broken, or will we hold on to the notion of intelligent life? Will it change our view of the universe and our planet? What will this great discovery lead to? Will we abandon the idea of being the chosen people, of being special? These months, I am not optimistic that it will do us any good, but I’m convinced that the paradigm will be broken.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.