Oldest-known remnants of archery in Europe discovered in Spain’s Bat Cave

The bowstrings, dating from between 7,200 and 6,900 years ago, are made of braided animal tendons, a technique modern archers still employ

Much has been written about the Cueva de los Murciélagos (the Bat Cave, in Albuñol, on the coast of Granada province). For a few years in the 19th century, it was Spain’s main source of natural nitrogen as a fertilizer (due to the guano of the bats that hung from its ceilings). Inside the miners thought they saw galena, a mineral rich in lead, in some reddish veins in the rock and went in to extract it. But above all, it was a cemetery, a necropolis that was later found to be very old. They removed almost everything: the 70 bodies that were there, the funerary objects and the offerings that accompanied them, most of which ended up sliding further down the cave, littering the path to the cavity, or as souvenirs in the homes of local residents. In 1867, a lawyer and archaeologist from Almería, Manuel Góngora y Martínez, who was also a professor at the University of Granada, went to the town, recovering everything he could by buying it from the locals or extracting it from the cave itself. Most of that material ended up in the National Archaeological Museum, but not all of it. Now, a century and a half later, a team of archaeologists has found the oldest-known remnants of archery in Europe in the waste dumps of the failed mine. According to a paper published in Scientific Reports, they found arrows still with their feathered fletching and tips made of olive wood or braided tendon strings, a technique modern archers still employ.

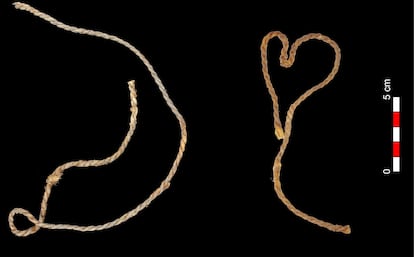

“We found one of the ropes between the rocks, where most of the bodies were thrown,” says Ingrid Bertin, a researcher from the Department of Prehistory at the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB). The other was one of those kept in the Archaeological Museum. At first glance, they appear to be made of plant fiber, “esparto grass, like many other objects found,” adds the French archaeologist. But after a more detailed analysis (with sophisticated techniques such as mass spectrometry or Fourier transform spectrophotometry) the researchers discovered that they were essentially collagen, of animal origin. They were able to refine it even further, seeing that one was made of ligaments from two different types of animals and the other from a third. Some probably came from a roe deer, others were from the goat genus, and the third tendons were from a domestic pig or a wild boar.

They also saw that the two bowstrings are from different periods. The Cueva de los Murciélagos was used for more than 3,000 years and always as a burial site. Those who arrived would place their dead on the ground, probably with their funerary offerings, and leave them there without burying them. The analyzed bowstrings are not so far apart chronologically, but it was striking that they were made with the same twisting technique, despite being made from different species and at different times. Raquel Piqué, the senior author of the research and also from the UAB, notes “the fact that the manufacturing technique is the same, although the raw material is different, shows a continuity in the way of making these objects that, on the other hand, are very similar to other strings that we find even now.” And she adds: “This technique of twisting the fibers is the same one that we use today, although with other materials.” The fact that they were made of tendons “is something that we did not have in European prehistory.”

In addition to the strings, the scientists also found arrowheads and shafts, with the feathers to give them balance still attached. Their dating by carbon-14 testing indicates that they are between 7,200 and 6,900 years old. The discovery of arrowheads is not new. In the Paleolithic, some 54,000 years ago, hundreds of carved stones were found for this purpose. The discovery then pointed to the idea that the technological superiority of Homo sapiens was decisive in the outcome of their encounter with the Neanderthals. “Indeed, archery already existed in the Upper Paleolithic, but only the points are preserved,” recalls Piqué. Hence the relevance of what was found in the Bat Cave. The shafts are made of cane, which means that the arrows are very light. The use of reeds for making arrows in prehistoric Europe, a hypothesis considered by researchers for decades, is finally confirmed.

Among the arrowheads found were those made of wood, specifically wild olive, a hard and dense wood like few others. To join the different parts, the researchers analyzed the ends of the shafts and arrowheads that still had the blackish remains of a material that turned out to be birch tar, a natural adhesive. Bertin says that they obtained it by cooking the tree bark over a slow fire. They did not do this with the fragile remains found, but they confirmed that they were good arrows when comparing them with the performance of other more recent ones, such as replicas of the arrows of some Native American Indians, such as the Apache. “We have the experimental work pending, because we want to replicate them and check their effectiveness,” she explains. They also have another task that could be groundbreaking if successful: to make this glue, which they also used to decorate the arrows, the prehistoric archers had to manipulate the tar and the researchers hope to find ancient DNA from those who did so.

What were the arrows used for? “We don’t know,” admits Francisco Martínez Sevilla, an archaeologist at the University of Alcalá, head of the Murciélagos Project (MUTERMUR) and also co-author of the research. Those who left their dead in the cave were Neolithic, living from agriculture and livestock. Although they still hunted, it was no longer the basis of their subsistence. So in life, they could have been used for hunting, but the researchers do not rule out that they were also used for war. “In the Levant, although they are somewhat older, there are cave paintings of interpersonal violence,” says Piqué. The oldest warlike use of arrows has also been found on the Iberian Peninsula, so they could well have had a dual use.

But the cave was also used for another purpose, probably symbolic. “There is no sediment there, so those who were arriving saw what others had left, adding their things, more dead, more offerings or whatever,” says Piqué. Unfortunately, the discovery of a gold tiara by the miners caused greed and poverty to destroy that place. “They used what was inside the cave, including the bones, to fill in the paths to it,” recalls Martínez Sevilla. Even so, the researchers have managed to recover more items from paths and dumps that shed new light on the first Neolithic people of the Iberian Peninsula. But this part of the history of the Bat Cave is still being written.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.