Esparto sandals found in a cave in southern Spain are the oldest known footwear in Europe

Neolithic farmers made the espadrilles 6,200 years ago with the same material that hunter-gatherers used for their baskets three millennia earlier

Almost 200 years ago, Juan Martín, owner of some land in Albuñol, in the southern Spanish province of Granada, discovered a cave not far from the sea. Difficult to access, it was full of bats and the floor was covered in guano. Those were boom times for Chilean nitrate, a fertilizer obtained from bird droppings. The Bat Cave became the main source of natural nitrogen in the Iberian Peninsula. In 1857, red veins were discovered in it, leading experts to suspect that it contained galena, a mineral rich in lead. It was the worst thing that could happen to the cave. Between the guano and the lead, between need and greed, miners plundered everything that was inside.

In the depths of the cavity they found a gallery converted into a cemetery, with dozens of partially mummified human remains and typical items of a funerary trousseau, including tools, bone awls, arrowheads, stone tools... There were also baskets and around 20 sandals made with esparto grass. The curse was completed when a gold diadem was found on one of the corpses. This unleashed a frenzy among the needy locals. Of the nearly 70 bodies, only the skull of a child is preserved in the National Archaeological Museum. It is now known that the basketwork and the footwear are the oldest in Europe.

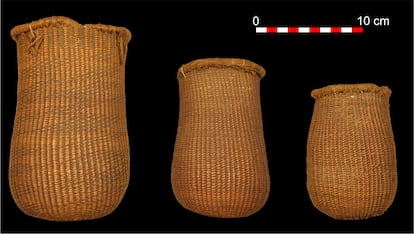

Collective research by around 20 scientists from different disciplines, from geology to history, has analyzed 14 of the dozens of esparto objects from the Bat Cave with current techniques and methodology. Francisco Martínez, an archaeologist from the University of Alcalá and lead author of the new study, highlights that there are two large groups of esparto objects and materials. “The four best preserved ones are about 9,500 years old, they are from the Mesolithic period, two millennia before agriculture arrived in the region.”

This means that those who made them were hunter-gatherers. That makes these items the oldest in southern Europe and, probably, in all of Eurasia. The baskets had, like everything else in the cave, a funerary use. Inside some there were still hairs and presents, such as poppy seeds, elements that are being analyzed and whose results will be shared at a later date as part of the Bat Cave research project, MUTERMUR.

A 19th-century discovery

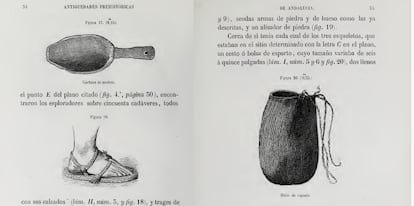

Ten years after the looting of the Bat Cave began, the Almeria-based lawyer and archaeologist Manuel Góngora y Martínez, who then held the chair of Universal History at the University of Granada, went to Albuñol and visited the cave. There he found scattered bones and objects, many charred by the fire of the mining boiler. Góngora recovered what he could, interviewed locals, bought dozens of archaeological remains from them and determined that they were prehistoric. His work occupies half of his 1868 book Prehistoric Antiquities of Andalusia.

Official archaeology, headed by the painter and archaeologist Manuel Gómez Moreno, questioned the authenticity of what was found in the cave. Góngora died without getting recognition for the value of what he had found, and his family donated his collection to the archaeological and anthropological museums of the time. It was not until a century later, in the 1970s, that the first particle accelerator in Madrid was able to determine through carbon-14 dating that Góngora was right. Years later, successive dating placed the materials at the beginning of the European Neolithic.

Other visitors to the cave left their own funeral baskets there, again made of esparto grass, over the following centuries. But there was something else. In his book, Góngora highlighted that he had recovered a couple of dozen espadrilles. “Almost all the sandals were children’s sandals, their size would correspond to a 37 today. They were buried in them,” says Martínez. Radiocarbon dating estimates an age of 6,200 years for them. Before this research, published in the scientific journal Science Advances, the oldest known prehistoric shoemaking was a type of espadrilles recovered at a site in Armenia and dated to 5,500 years ago. By comparison, the type of leather ankle boots over plant fiber sandals worn by Ötzi, the “ice man” discovered in the Alps, are 5,300 years old. Beyond the dating, what fascinates Martínez is that two worlds as different as that of hunter-gatherers and Neolithic farmers “are united by esparto grass.”

María Herrero, a researcher at the Autonomous University of Barcelona and co-author of the study, is working on a thesis on prehistoric plant fibers. Regarding basketry, Herrero recalls that even older fragments of esparto grass have been found at the Les Coves de Santa Maira site (in Alicante province), dating back 12,500 years, but “there is nothing comparable, so well preserved, with so much decoration and variety.”

As for the sandals, “there is no footwear prior to espadrilles in Europe,” she adds. In most cases, only the soles remain, but there are a couple of them that still preserve parts of what must have been strips that “would cross as they do today in beach sandals and attach them to the ankle.” The illustrator of Góngora’s book drew them 150 years ago (see image below). Although all the esparto grass found in the cave had funerary uses, Herrero highlights a marked difference. The baskets and other unidentified objects from the Mesolithic, the oldest, were not used or worn out, “they were part of the offering.” Meanwhile, the later baskets and sandals, the Neolithic ones, were worn and “had accompanied the deceased in their lives.” Regarding the technology, Herrero highlights that “some techniques used, such as sewn spiral basketry, are common to both periods, but also connect the cave with other sites, such as La Draga, in Banyoles, Girona.” Even today, the researcher highlights, “esparto grass continues to be worked like they did in the Bat Cave.”

Part of the wonder of this story is that prehistory has been written by things that last: the bones of human fossils, those of animals converted into utensils or weapons and, above all, stones. Not in vain, the great prehistoric periods - Paleo, Meso or Neo - carry the lithic suffix, which means stone. This is also there in the Bat Cave, but almost nowhere else did objects survive made from fibers obtained from a grass, Macrochloa tenacissima. In other parts of the world, the perennial plant displays flat leaves, but in arid areas such as Albuñol, they curl up on themselves forming threads.

The problem is that everything made with organic materials is doomed to disappear, especially in a cave. “In any other place the baskets and sandals would have disappeared. Organic matter disappears fundamentally because of water, which facilitates the proliferation of bacteria that eat organic matter,” explains José Antonio Lozano, a geologist from the Canary Islands Oceanographic Center and co-author of the study. But there is no humidity in the Bat Cave “due to the climate of the area and the topography and morphology of the cave.” Furthermore, the position of the cavity facilitates the arrival of winds that dry out the interior even more. “This means that there are hardly any speleothems [stalactites or stalagmites, for example]. It is unique in Europe.”

The same dry air that preserved the sandals also mummified their bearers: 155 years ago, the archaeologist Góngora y Martínez wrote in his book that the grotto must have had something special, lamenting its plundering: “The dryness of the place, the nitro with which the walls were covered [and] another agent difficult to point out, had perfectly preserved the corpses, outfits and utensils. More than 40 centuries have respected that necropolis. Do not tear it to pieces in one day like madmen and fools.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.