‘It is a machine of destruction’: The wels catfish threatens Spain’s river ecosystems

The invasive species, native to the rivers of central Europe, is already found in a large part of the main basins of the Iberian Peninsula and is a danger to native fauna

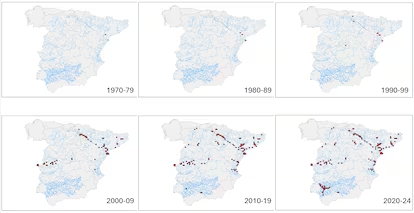

“The fish is not to blame; those responsible are the people who have brought it here,” says fisherman José Manuel García while examining a huge wels catfish measuring 1.6 meters and weighing 25 kilos that he has just caught in the Iznájar reservoir in the Guadalquivir basin in southern Spain, where the species first appeared in 2011. “There are bigger ones,” he says before killing it, as required by law as it is an invasive exotic species. The wels catfish — the largest freshwater fish in Europe, which can reach a length of 2.5 meters and weigh over 120 kilos — has not stopped multiplying and wreaking environmental havoc since the German biologist Roland Lorkowsky introduced 32 fry from the Danube into the Segre river, in the Ebro basin, in 1974.

Since then, the species, which originates from central Europe, has colonized most of the main basins of the Iberian Peninsula. This expansion has been made possible due to fishing enthusiasts transporting it from one place to another illegally and without taking into account the environmental consequences. Other fishermen like García, president of the Environmental Association of Fishermen of the Iznájar reservoir (Amapila), are trying to stop these practices and convince their colleagues of the devastating effects they cause in Spain’s rivers.

In Iznájar, native species such as the common barbel and bogue are becoming increasingly scarce, while others, such as carp and black bass, have been introduced. “It is a machine of destruction that eats between 2% and 4% of its body weight every day. It has even been detected that it can catch ducks and geese and other birds such as cormorants, of which we have found remains in its stomach”, says Carlos Fernández, professor of zoology at the University of Córdoba and head of the Stop Catfish program, on the shore of the reservoir. This research, promoted by the Ministry for Ecological Transition, aims to determine the distribution area of the species in the Lower Guadalquivir and to develop a management plan.

Despite the damage they cause, some fishermen have continued to transport catfish to other areas, despite regulations stating that their capture is only allowed in areas where they were found before the 2007 natural heritage law came into force, such as in the Mequinenza reservoir, in the province of Zaragoza, where a lucrative business has developed around sport fishing for the species. “They want to have [the fish] close to where they live,” says the president of Amapila.

“There are people who think that the introduction of species increases diversity and local wealth, but what is produced is a global loss,” explains biologist and University of Girona professor Emili García-Berthou, an expert in inland fish. These new inhabitants — in this case the catfish — cause the disappearance of native communities and fauna and flora to become increasingly similar between countries.

Amapila fishermen are aware of this loss of diversity. “We miss the times when we used to catch 20 or 30 barbel. Now, if we catch one, we are happy,” says García, while measuring the catfish he has just pulled out of the water in Iznájar. When they catch a specimen, they collect all the information available to them: size, diet, whether it is male or female, which they then send to the researcher Carlos Fernández.

The Amapila association has the permission of the Andalusia regional government to extract catfish from the marsh and thus help to contain them, with similar agreements in place with the Association for Fish and Aquatic Ecosystem Conservation (Acpes). However, the fishermen who are trying to solve the problem created by others complain that they are doing it with their own means. “The only thing we have received from an administration were some mortuary bags that the city council of Rute gave us, but two catfish fill them up and you can’t put them in the car; you’d never get rid of the smell,” says García.

As he speaks, the catfish, with its head, wide and flattened, small eyes, two large whiskers and mucous-covered skin, lies still on the ground. “What a useless death. The fishermen who allowed them to expand should see it,” says another Amapila member. Catfish can modify the ecology of an area, warns Fernández. In the Guadalquivir, it threatens the breeding and fattening area of numerous species of commercial interest (anchovies, sea bass, corvinas, red crab) that are exploited in the Gulf of Cádiz, according to the research carried out by Stop Catfish.

Stopping the advance of the catfish, an almost impossible mission

“The only solution is to eradicate the species in time,” says Fernández, something that was not achieved in Iznájar and many other places in Spain. “It is impossible to stop the advance of an invasive species like the catfish only with what fishermen can catch, without any scientific method or planning,” he adds. In the Guadalquivir basin, the scenario became more complicated in 2017, when two specimens appeared in the Rivera de Huelva river, a tributary of the Guadalquivir. Someone had released them into the waterway. “After collecting data, we have found that the problem is everywhere,” says Fernández. “Maybe some habitats are not suitable for the species and it will die, but in the meantime it will be eating and damaging the ecosystem.”

Amapila fishermen say it is not even an attractive animal to catch. “All you do is pull, pull, pull, as if you were taking the plug out of the marsh. It’s not like the barbel or black bass, which pulls, loosens, you give it reel, it makes its runs...” There are other enthusiasts, however, who enjoy the struggle of catching the huge fish and even travel from other European countries to do so in the few places where it is allowed. However, there is also poaching and illegal trafficking. In 2019, the Spanish Civil Guard arrested 23 people for the illegal fishing of 13 tons of catfish and carp in the Ebro, whose destination was Romania and other eastern European countries.

Disaster for sport fishing

“The Tagus has been greatly affected. Extremadura is a paradise for freshwater fishing, there are trout, cyprinids, native fish of all kinds and the catfish does a lot of damage,” says Miguel Bonifacio, president of the Extremadura Fishing Federation. “You realize that you are no longer catching native fish and that is a disaster for sport fishing, because the places where we can hold competitions, which bring money to the towns, are fewer and fewer,” he says.

For Bonifacio, there is no solution once the species has a foothold. “It is necessary to police the people who catch them to move them somewhere else, it is ignorant behavior.” He asks the administrations not to look the other way. “The hot spots where people go to catch them are perfectly well known. As soon as they start handing out fines, the story is over,” he concludes.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.