The melting of Antarctic ice surprised emperor penguin chicks: ‘Data indicate that they did not survive’

In 2022, four West Antarctic colonies collapsed because ice melted before the chicks were physically able to escape

Climate change and its consequences have been talked about since the turn of the century. Back then, iconic images of a polar bear on a tiny patch of ice surrounded by the vast Arctic Ocean helped show the extent of the coming drama. Now that tragedy has moved south. Last year, four colonies of Antarctic emperor penguins failed to raise their young. Their parents nested on icy water surfaces, but in the Antarctic summer of 2022, the ice melted before the chicks had exchanged their down for the hydrophobic feathers that would have allowed them to submerge themselves in the icy Antarctic waters.

The adult pairs had to leave the colony and abandon their offspring, who either drowned or starved to death on tiny icebergs, much like those of the polar bears in the north of the planet.

The emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri) is the largest penguin and the biggest warm-blooded animal that lives this far south. Discovered last century by Russian explorers, the animal lives and nests only in Antarctica. It has not been hunted or fished by humans (except by chance). Nor has its habitat, Antarctica, been seriously altered. So, it was thought to be an iconic species that was free of threats, which has made the emperor penguin a bellwether of climate change.

That status stems from the fact that their life cycle follows the ice cycle. Penguin pairs arrive at the edges of the continent between the end of March and April, when it is autumn. The eggs hatch in July, when that ice’s maximum extension occurs. And so it goes, as the chicks grow with their gray down, which protects them from the cold. Under normal conditions shaped by natural selection and climate, the young penguins gradually lose the layer that protects them from the cold in favor of highly water-resistant feathers rich in fat in mid-December. That is when the sea ice, which has been cracking since October, sometimes disappears completely, facilitating the chicks’ transition from terrestrial to marine life. But in 2022, everything fell apart.

When the ice supporting the ramp disintegrated, the parents would no longer have been able to reach their colony. The chicks would have died here of starvation or frostbite.Norman Ratcliffe, British Antarctic Survey

Of the more than 60 colonies that have been discovered, only three nest on continental ice, that is, inland. The rest nest on land-fast ice. That variety is neither continental ice nor sea ice, the part that rests on sea water. It is the frozen portion of ice that is still in contact with the submerged continental shelf. Researchers from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), a scientific organization that has been on the continent since 1962 continuously, observed an anomalous melting on the westernmost edge of Antarctica. On the shores of the Bellingshausen Sea (named after the aristocrat who led the expedition that first sighted the emperor penguins), there was no more ice in November, leaving only water under the feet of birds that don’t fly and were unprepared to swim.

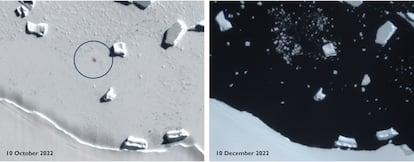

“There is evidence that the chicks used a stranded iceberg as a kind of lifeboat at one colony, but the satellite data suggest that they did not survive there until they fledged,” says Norman Ratcliffe, a BAS researcher. Ratcliffe and his colleagues used Sentinel2 satellite data to observe two processes at the same time: ice shrinkage and change in plumage. In early December 2022, ice extent marked an all-time low. There is no direct evidence about what happened to the chicks based on scientists’ observations on the ground, but, as Ratcliffe says, “if the sea ice breaks up under the colony before the chicks have waterproof feathers in early December, they will either fall into the water and drown or drift away on floes, losing their parents.”

Scientists analyzed images taken of this area of Antarctica during the penguins’ entire breeding cycle. In the central and western part of the Bellingshausen Sea, there are five emperor penguin colonies. From the sky, they look like dark spots on the snow, the grayish brown of the young combines the brownish color of the guano, their droppings. In December 2022, the ice melting represented historic lows over the entire Antarctic Peninsula, but by November 100% of the sea ice in the Bellingshausen Sea had already disappeared.

Researchers described the consequences in an article that was just published in the scientific journal Communications Earth & Environment. Of the five colonies in the area, three were abandoned in early December and a fourth, at Verdi Inlet, with some 3,000 pairs, was abandoned even earlier, in November, two months before the young molted. There were no field checks. The five colonies were discovered in the last decade, and there are no bases in that region of Antarctica. All that is known about them comes from satellites. The satellite images show that long before the chicks had their hydrophobic feathers, there was water where there should have been ice.

The most dramatic case was likely the Pfrogner Point colony. Discovered in 2019, it consists of about 1,200 pairs and is among the few colonies nesting on continental ice. The satellite images show the brownish patch until October. But in the November 8 image, it was no longer there, and on November 12 there was no sea ice. It seems unlikely that the hatchlings fell into the water, but the alternative Ratcliffe describes is worse: “Ice shelves often have a steep cliff on the edge facing the sea that penguins cannot normally climb. At Prfogner, a snow ramp had built up on the sea ice below the cliff that allowed access. When the ice supporting the ramp disintegrated, the parents would no longer have been able to reach their colony. The chicks would have died of starvation or frostbite.”

So far, sixty-two emperor penguin colonies have been discovered in Antarctica. There are a few small colonies and a few thousand pairs in the Bellingshausen Sea. In the southern and northern Antarctic, there are clusters of up to 20,000 pairs. In addition, climate change’s impact on Antarctica is more complex and less clear than it is in the Arctic. For decades, ice has increased in the eastern portion of the continent, while in the West Antarctic, ice is melting at a faster rate. But if greenhouse gas emissions continue at the current rate, most of Antarctica will lose most of its seafloor and fixed ice sooner and for a longer time. Based on these models, a 2020 study estimates that 90% of the colonies could disappear by the end of the century.

The lead author of the study, Peter Fretwell, also of BAS said, “We know that emperor penguins are highly vulnerable in an increasingly warmer climate, and current scientific evidence suggests that extreme sea ice loss events like this will become more frequent and widespread.” Although only four colonies collapsed last year, between 2018 and 2022, 30% of the 62 known emperor penguin colonies were affected by partial or total loss of sea ice. Based on previous local collapses, scientists know that emperor penguins move their nesting grounds. In a BAS article, climatologist Caroline Holmes explained what may happen this season: “At this time, in August 2023, the sea ice extent in Antarctica is still well below all previous records for this time of year. In this period when the oceans are freezing, we are seeing areas that, surprisingly, are still largely ice-free.” Where will the emperor penguins go to raise their young?

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.