Face blindness and the life stories that are etched in bone

Prosopagnosia occurs when the world is lost as a representation and we stop recognizing the faces of our relatives and those close to us

We tend to recognize people by their faces, not their knees, says forensic anthropologist Sue Black in her 2020 book Written in Bone: Hidden Stories in What We Leave Behind, which has just been released in a Spanish translation.

We can easily recognize people with whom we have been in constant contact for some time by their faces. But when we stop identifying the faces of the people closest to us, then we are talking about face blindness or prosopagnosia, a neurological condition, the most famous case of which is the one that lends the title to the book by the British neurologist Oliver Sacks; The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, in which Sacks tells the story of a musician who came to his office thinking that his problem was not neurological, but concerned his vision even though the ophthalmologist had referred him to a neurologist.

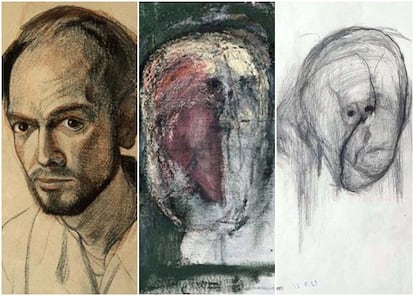

At the end of the visit, when he goes to put on his hat, the musician grabs his wife by the head and tries to lift it off to put it on, according to Sacks. Days later, the neurologist goes to visit the musician at his home. Once inside, Sacks is amazed by the pictures painted by his patient. Their evolution is striking, as they have gone from the concrete to the abstract. A naturalistic and realistic period has developed to become cubism and, ultimately, an absurdity. “This wall of paintings was a tragic pathological exhibit, which belonged to neurology, not art,” wrote Sacks, who then delves into the essence of creativity when it is accompanied by a mental imbalance.

In his view, the relationship between pathology and creativity is one of tension, which somehow conspires to trigger the creative spark. But that was not the issue. The issue was that this man had lost the world as a representation, even though for him the world continued to exist as music or will, as Schopenhauer said when he defined music as pure will.

That man suffered from prosopagnosia, a disease whose term was coined by the German neurologist Joachim Bodamer after World War II, when he described the case of a 24-year-old man with a bullet wound to the head that hampered his ability to recognize his relatives and even his own face when he looked in the mirror.

Returning to the work of Sue Black, her book explains that our bones, like our thoughts, are a mystery that remains hidden and wrapped in our body. Our bones can reveal the history of our life and forensic science can interpret them, deciphering all our secrets, to the point that the history of a murder can be reconstructed from them.

Sue Black’s book contains many other books within it; it is a scientific tome that crosses the frontiers of forensic science and ventures into Oliver Sacks’ territory.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.