Sue Black, the forensic anthropologist who hunts pedophiles by the shape of their hands

The Scottish scientist and Life Peer is leading a European project to create an artificial intelligence recognition system for use by the continental police forces

In 2006, a girl in the UK said that her father was abusing her. Her mother didn’t believe her. The girl decided to place a camera in her room. In the middle of the night, her father entered the room and abused her again. In the video footage captured by the girl, only the forearms and hands of her abuser could be seen. The police called in Sue Black, a world-renowned forensic anthropologist who had spent decades identifying nameless corpses, first in her native UK and then in some of the the worst war zones on the planet. “Can you identify the man in the video?” the police asked.

The rest of the story would provide enough for a documentary series and underlines how the field of forensic science is changing - because crimes are also changing. Fewer and fewer crimes are committed in the real world and more and more are taking place in the virtual world, particularly scams and sexual abuse, says Black during an interview with EL PAÍS. “If you’re robbing a bank, you don’t film yourself robbing the bank. But if you’re going to abuse a child, often you will film it because you want to relive the experience, you want to share it with like-minded people, or, in fact, as a commodity that you can sell,” says the president of Saint John’s College at Oxford University, who recently published an award-winning book detailing real life cases titled Written in Bone: hidden stories in what we leave behind.

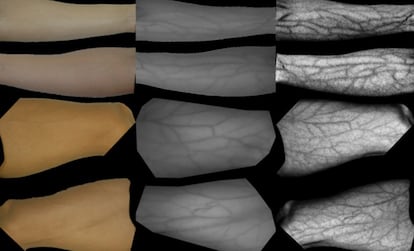

In the 2006 case, the camera that the girl left recording in her room at night emitted infrared light. “When infrared light touches the skin, it interacts with the deoxygenated blood that sits inside your veins. And your veins stand out like black tramlines. So we could see in this nighttime image the pattern of veins on the back of the hand, in the forearm of the perpetrator, and nobody knew what to do with this.” Black explains. “So the police came to me saying: ‘You’re an anatomist. What can you tell us about veins?’ And I said, Well, the one thing we know for certain about veins is that the veins on the back of your right hand will be different to the pattern of veins on the back of your left hand, and if an identical twin, they will be different. As far as we’re aware, there are no two patterns of veins as yet that are the same.”

Black’s analysis confirmed that the girl’s father was the aggressor and she herself explained it to the jury. It was the first time such evidence had been admitted in a UK criminal court. The verdict, though, was returned not guilty. Stunned, Black asked the prosecutor what they had done wrong. “You didn’t do anything wrong,” the prosecutor replied. “Your evidence was absolutely fine. The jury didn’t believe the girl because she didn’t cry.”

Since that case, the forensic anthropologist has focused on identifying criminals through veins, knuckles, freckles, scars and other unmistakable features of their hands. Her reports have been admitted as evidence in numerous trials and have contributed to life sentences for 30 offenders in the United Kingdom. Black says that in about 82% of the cases in which she and her team identified the defendant, they changed their plea and confessed to the crime. “And that was an incredible step forward for us because it meant young girls now weren’t having to go into court to give evidence against their father like the young girl we had,” she says.

One of the most high-profile cases to cross Black’s desk was that of Richard Huckle, who was handed 22 life sentences after confessing to at least 71 assaults on minors, most of them committed in Thailand. In 2019, Huckle was stabbed to death by another inmate with a dagger made from a toothbrush.

In 2018, Black acknowledged having been abused as a child. She did not report her assailant because he was a family friend. In any case, she said it “had no influence on my professional choices. When I started identifying the hands of pedophiles in 2006, my career was already consolidated, so there is no correlation.”

Black’s team recently received a prestigious European Union grant of €2.5 million to develop an artificial intelligence-based hand identification system. “Your vein pattern doesn’t change: it’s set down when you’re a fetus. What we want to be able to do is to train the computer to be able to find a hand within a video or an image, to then be able, if you can see that hand, to extract the vein pattern or extract the skin crease pattern, to be able to do all the things that we would normally have to do as an expert witness,” she explains.

Black’s team are training the algorithm with thousands of photos of hands provided by anonymous volunteers: only the gender and approximate age are known. There are two or three images of each volunteer and the objective is for the machine to be able to identify one person among thousands, with a miniscule margin of error.

This biometric data could be added to other more traditional evidence tests such as DNA and fingerprinting. “If you can load all this information into a unified database, fingerprints, wrinkles, veins... the chances of being mistaken for another individual could be as high as one in many millions,” Black points out.

The researcher believes that the first prototype may be ready in two years. Then it would be delivered to Interpol or Europol so that they are able to identify criminals with a hand scanner. This type of recognition is on the rise, says Black. There are similar studies in Germany, India and Japan. The first paper on this technique was published by South Korean scientists in 2000, according to a study carried out by the scientific office advising the US president.

In her new book, Black takes a tour of the human skeleton, recalling bone by bone many of the cases she’s been involved in since she was a forensic anatomy student in the early 1980s.

Her father was a hunter and from the age of five it was she who gutted the rabbits and plucked the pheasants. At the age of 12, she started working in a butcher shop. She spent her teenage years “up to my elbows in blood and muscle and bone and guts.” When she went to university, she took up biology without having a clear idea of what career path to pursue. In her second year, she was asked if he wanted to help out on a case. An unidentified body had been found off the coast of Scotland. It had been in the water for more than two weeks. It wasn’t possible to obtain fingerprints and the face was mangled, possibly by a ship’s propeller. Black accepted and analyzed the corpse. It was a young man. With Black’s assistance it was possible to identify his height and his ethnic background. A birthmark was also found under the left nipple. They identified a missing person with the same characteristics and asked his mother, who said her son had no birthmarks. But when they asked the missing man’s girlfriend, she confirmed he did have one, under the left nipple. The mother refused to accept the evidence and the case was closed without an official identification announcement.

Black is perhaps the only person in the world ever to have traveled with two decomposing human heads in her carry-on without being stopped. The Italian Carabinieri had asked her to help identify two victims of Gianfranco Stevanin, a serial killer known as the “Monster of Terrazzo,” who killed six women in northern Italy in the early 990s. Today, that odyssey would not have been necessary and a simple scan could have been sent by email to make the identification, Black notes.

The case that affected Black the most occurred during the war in Kosovo. A farmer and his family had left their village and taken to the nearby hills to avoid the bombing, returning only when they needed supplies. One day, the farmer was driving his tractor with the whole family traveling behind in a trailer when a rocket-propelled grenade struck. His wife, sister, grandmother and eight children were all killed. He was shot by a sniper, but survived.

A year later, Black was called in by the United Nations to find the remains of the family and determine whether a war crime had been committed. “And what [the father] wanted more than anything was a body bag back for each of his family members, because his biggest concern was that because they were all buried together, his fear was that his God would not be able to find them, and if he could give them each a grave then God would be able to find each of those family members,” she recalls. There were hardly any remains to work with, but the forensic anthropologist, an expert in child anatomy, managed to identify all but two: 14-year-old twin boys. The remains could not be separated and the DNA was identical. One of the corpses was wearing a Mickey Mouse T-shirt. The father was asked if any of his children liked the cartoon character and without hesitation he said the name of one of his sons, who was obsessed with Mickey Mouse. “I think my whole reason for being in Kosovo was that case, that I was in the right place at the right time to help that man with what he needed to find his own closure.”

Black was recently created The Baroness Black of Strome, when she was appointed as a crossbencher Life Peer in the House of Lords. She is nonpartisan and says her remit is to provide expert opinion on science, education and immigration law, for example, finding better ways to determine the age of an unaccompanied minor with medical tests. She also makes television appearances and even has a portrait in the National Galleries of Scotland, titled Unidentified Man, in which she poses in front of a body covered by a green sheet in a dissection room.

Black says he has donated her body to the anatomy department at the University of Dundee for students to practice dissection on. “I want every single bit of me to be dissected. I don’t want anything left unexplored, and I want it to form the basis of this young people’s education that they can remember, like I do, the cadaver that I learned from. I’d quite like my bones to be strung up into a hanging skeleton. And that way I can be in the dissecting room and I can carry on teaching. My daughters are very pragmatic. They grew up in the kind of environment where my husband and I would happily talk about such things. And it was my youngest daughter, who is the trainee lawyer, who said, actually mum it’s quite cool because normally when parents die, all you can do is visit a grave site or whatever. We could actually come and visit you.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.