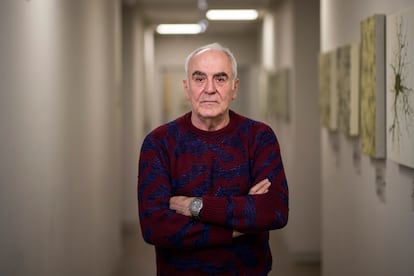

Neuroscientist Javier de Felipe: ‘I would love to become a dog for a few minutes’

A new book explores how brain research helps us understand what it means to be human

Javier de Felipe says that after decades of research, he is finally beginning to understand a few things about the brain. “And now they want me to retire,” he says ruefully. De Felipe is one of the most prominent neuroscientists in Spain, the country that produced Santiago Ramón y Cajal, considered by some to be the first neuroscientist. At the Polytechnic University of Madrid’s Center for Biomedical Technology, he studies the microanatomy of the cerebral cortex to understand things like how ideas arise, and the brain abnormalities of epileptics. He also directs the Cajal Blue Brain project, which is developing a simulation of brain function at the molecular level. De Felipe also participated in NASA’s Neurolab research on the effects of space flight on the brain, and in ambitious international initiatives like the Human Brain Project.

De Felipe recently published De Laetoli a la Luna (or From Laetoli to the Moon), a new book that traces humanity’s journey from the first upright hominid (the footprints discovered at the Laetoli site in Tanzania) to the Moon landing. He says that this journey parallels the history of the brain, “the part of the body that defines our humanity.” The book integrates decades of scientific research with his own insights and observations about literary classics to explain why the history of neuroscience is also a story about what it means to be human.

Question. Do you believe that neuroscience will help us answer existential questions such as why we are here or where consciousness comes from?

Answer. The brain’s greatest mysteries are processes like memory, intelligence, imagination, ideas, how neurons connect – all the sparks in our brains that produce those things. We still don’t understand them. Maybe the brain is a physical creation or maybe it evolved to the point where we can have memories, ideas and abstract thinking. Then again, maybe we’re just automatons.

Q. The subtitle of the book is, “The unusual journey of the human brain.” Why are our brains unusual? Are they really so different than the brains of other species?

A. Our brain has many things in common with other mammalian species, including many characteristics that we think of as very human. Like us, chimpanzees teach their offspring to do things, and dogs also get depressed. I used to think that these characteristics were very particular to human beings. But the brains of diverse species are all different – no two are alike. For example, the retina is the entry point for information processing, but human retinas are not the same as cat and dog retinas. The mental worlds of humans and dogs are completely different even though we live in the same environment.

Some of my colleagues think that the complexity of the human brain is the only thing that distinguishes it from other species. But we have unique cells that we can associate with our properties. Just because we’re unique doesn’t mean that we are better – all the other species are also unique. A lion’s brain is totally different from a giraffe’s brain, which is totally different from a rat’s brain. I would love to become a dog for a few minutes, just to understand what it means to be a dog and what a dog’s world is like. That would be wonderful.

Q. In the book you discuss some of the most puzzling leaps in history, such as the Big Bang forming the universe, the appearance of the first life forms and the emergence of consciousness.

A. For reasons unknown, the complexity of our brain has enabled us to travel to the Moon. How is this possible? How could everything suddenly appear out of nothingness, and then the human brain emerges as well? I am interested in these great leaps – the appearance of matter, life and the human brain. And then we have these incredible similarities. An astrophysicist once showed me a computer simulation of the universe, and the images of enormous galaxies connected together by gravitational filaments looked like a network of tiny nerve cells.

Q. Did human consciousness evolve gradually or do you see it as a leap, like the appearance of matter and life?

A. I believe human consciousness evolved gradually, but this is still being studied. About 40,000 years ago, we saw the beginnings of what is called the human revolution. This is when people started making objects like the lion man – a figurine or drawing of a human with a lion’s head. These are signs that those humans were capable of abstract, symbolic thought. Even Homo erectus – the first species to walk upright – made some geometric marks on objects. But the human revolution really began about 30,000 years ago when the Venus figurines and the Altamira (Spain) paintings were made. But when did man begin to enjoy poetry, literature, and writing? Writing first developed 8,000 years ago, beginning with rudimentary symbols.

Our neuronal forest has remained the same for millennia, and I am sure that our ancestors watched sunsets and enjoyed them as much as we do. But they could not write about sunsets. This leads me to think about mental illness. Many of the greats in science, music, and painting had psychiatric problems. Rubén Darío wrote about people with a “divine madness,” to whom we owe human development. Their brains work in abnormal ways, a daydreaming state that enables them to see things that others cannot. In early human history, we may have had the basis, but not the environment. Think about it – a divine madman long ago does something that suddenly changes your world, like inventing a tool or the wheel. Then everyone starts to imitate and build on this invention, and humanity advances.

Q. How do you think artificial intelligence will ultimately emerge if it ever does? Do you think someone will push a button and there it is, or will it surface unexpectedly out of some sort of crisis?

A. We have invented machines that can do some things much better than we can, like machines that add and subtract. There was a time when everyone thought that the game of chess was sublime, and no machine could ever defeat a human. But then IBM’s Deep Blue computer beat Garry Kasparov. That was incredible at the time, but now we have $50 computers that can beat any chess champion. It’s a pity. We have machines that can create music, and contests to guess whether a composition was created by a machine or a musician. I believe that we will have intelligent machines someday, but some things will always be unique to humans – the perception of sadness or color, for example.

Q. In your book, you quote Richard Feynman: “What I cannot create, I do not understand.” How can we think about creating intelligent machines when we can’t even cure Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease?

A. We are still very far from understanding how the brain works. Studying complexity is difficult. The problem is that almost everything we know about how the brain works is based on experiments in which we manipulate the circuits and genes of animal brains to see how they work. Then we try to extrapolate that to the human brain, but it’s different from a mouse’s brain.

We are now trying to develop technologies that will enable us to study the human brain directly. We conduct detailed laboratory analyses on brains donated by people who have died. We don’t have many techniques for this yet, but we do have a few that are very powerful. We can make models of human neurons based on real data, not on extrapolations from animals. Little by little, we are gaining more and more information about the human brain. I am optimistic about the knowledge we will have in the future.

Q. Science fiction is full of interstellar travel and artificial intelligence, but they still seem very far away for us.

A. Our imaginations are always far ahead of science, but we’re getting there. I remember watching Star Trek when I was a kid and seeing people making video calls. It seemed absurd at the time, but now we can do that on our mobile phones. There are things that we once thought were impossible and now they’re here because of education. Michelangelo’s sculpture of Moses was possible because he was a genius, but also because he had an education – someone who taught him to handle a chisel and study shapes. How many people like Goya, Picasso, Dalí, scientists and writers have we missed throughout human evolution because they didn’t have the right environment?

There are many children who could be great geniuses but never flourish because they don’t have access to education. I would invest much more in education. If we used all the money that is spent on missiles and bombs for education or eliminating hunger, we would be living in a paradise. The cost of one missile is enough for me to do two years of research. If I were a politician, I would put much more money into education, which would make for a better society. But politicians see that as dangerous because well-educated people can’t be easily manipulated.

Q. Will detailed knowledge about how the human brain works put an end to the illusion of free will?

A. Spinoza said people think they are free because they are aware of their actions. But we don’t know why we do things. You get up in the morning and drive to work. It’s automatic – you’re not thinking all the time about your belief system when you do things. We follow rules and routines of our own invention. People talk about traditions that perhaps started less than 200 years ago. Back in the days of the gladiators, people delighted in the goriest human suffering. That is unacceptable nowadays. Our evolutionary process is characterized by increasingly civilized brains, and we are becoming more and more human. Of course, atrocities still happen, but they are fewer and fewer. There is increasing respect for human rights.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.