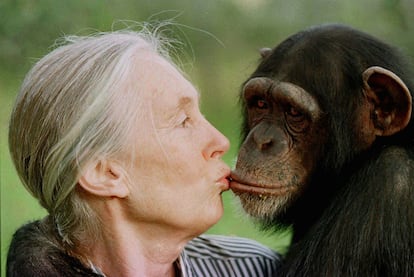

British primatologist Jane Goodall dies at 91

She revolutionized science since the 1960s with her innovative methods and fascinating discoveries about wild chimpanzees

British ethologist and primatologist Jane Goodall died on Wednesday at the age of 91 from natural causes, according to a statement posted on social media by the institute that bears her name, which she founded in 1977 with the aim of promoting the protection of ecosystems and biodiversity. A United Nations Messenger of Peace, Goodall was noted for her innovative methods and fascinating discoveries about the behavior of wild chimpanzees in Gombe, Tanzania. At the time of her death, she was in California as part of her lecture tour of the United States.

The famous Planck’s principle states that science progresses “from funeral to funeral” because one generation, always reluctant to change and embrace new ideas, must die before the next generation can naturally accept advances. In Goodall’s case, this was not necessary because she achieved immediate success with the complicity of an audience fascinated by her documentaries for National Geographic.

“She took an unorthodox approach in her field research, immersing herself in their habitat and their lives to experience their complex society as a neighbor rather than a distant observer and coming to understand them not only as a species, but also as individuals with emotions and long-term bonds,” explains a bio on the Jane Goodall Institute website. “Her field research at Gombe transformed our understanding of chimpanzees and redefined the relationship between humans and animals in ways that continue to emanate around the world.”

Born in London, Goodall grew up in the postwar period in her family home in Bournemouth, southern England. It was a large farm with cows, pigs, and horses. There, Goodall became obsessed with finding out how an egg could come out of a hen, so she hid in one of the six chicken coops on the property and waited. She crouched there for four hours until she saw the bird lift its wings slightly and drop a white egg onto the straw. That, according to the ethologist, was the birth of a young researcher.

Unable to afford college, she ended up training to work as a typist and bookkeeper. She needed money to help support her family, and ended up working in a tedious secretarial job. She never stopped thinking about Africa. With extra work as a waitress, she managed to save enough money to travel to Kenya at the age of 23, thanks to an invitation from a friend to his family farm in Nairobi.

She immediately received a job offer from the famous anthropologist Louis Leakey, who noticed her keen powers of observation. Her lack of formal experience as a scientist — and therefore free from the vices of the profession — and her passion for animals convinced the professor that she was the ideal person to study the social life of chimpanzees. In 1960, he sent her to Gombe (Tanzania) with the risky mission of researching the wild specimens of the species that inhabited the area for the first time. The results of her field research made an impression on the scientific community and fascinated the whole world through the documentaries she starred in.

Thanks to Leakey’s influence, Goodall was finally able to pursue a doctorate at the University of Cambridge in 1962, despite not having the necessary degree. She was not particularly enthusiastic about the academic world, as she herself acknowledged, but she completed her thesis to show her gratitude for the effort and trust placed in her. Her fellow students treated her with ignorant condescension and mocked her for giving the chimpanzees names. “I didn’t give them personalities, I merely described their personalities,” Goodall explained to the BBC.

“From my point of view, you can have empathy and you can also be objective at the same time,” she said in her last interview with this newspaper in May. “I remember, once, a little chimp: she’d broken her arm. Every time the mother moved, the baby cried. So, the mother tightened her grip, which hurt even more. I was just crying. But, if you read my notes, it’s accurate to the minute. You can have empathy and observe objectively,” explained the primatologist, who has published some 30 books and made more than 20 television productions. Lorenz Knauer’s biographical documentary, Jane’s Journey, was shortlisted for an Oscar in 2012.

Goodall received numerous awards throughout her life. Charles III of England, a great lover of nature and wildlife conservation, awarded her the title of Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire, and the then-U.S. President, Joe Biden, personally presented her with the Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award given by that country.

In her later years, the primatologist became increasingly pessimistic about the future of the planet, while continuing to call for action. “If we don’t get together and impose tough regulations on what people are able to do to the environment — if we don’t rapidly move away from fossil fuel, if we don’t put a stop to industrial farming, that’s destroying the environment and killing the soil, having a devastating effect on biodiversity — the future ultimately is doomed,” she told the BBC in one of her last interviews. Goodall never stopped working. On stage, at numerous events; collaborating on podcasts or giving talks. She had one scheduled for this Friday in California, and another four days later in Washington, D.C.

When she turned 90, Vogue magazine asked her to summarize her thoughts in nine pieces of life advice. Work hard, seek common ground to understand others, have empathy, support your children, don’t be afraid to change your mind, convince yourself that we can all have an impact on the planet with our actions, be true to yourself, and take action — don’t stand still. And above all, she added, be clear that everything happens for a reason. Like that trip to Kenya that changed her life and helped thousands of people see animals in a more humane and empathetic way.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.